The mission of an ice-hunting cubesat is officially at an end.

NASA officials announced Thursday (Aug. 3) that the agency had ceased operations earlier this year on its Artemis 1 moon mission ride-along cubesat, called LunaH-Map.

NASA is cautiously testing OpenAI software with a range of applications in mind, including code-writing assistance and research summarization. Dozens of employees are participating in the effort, which also involves using Microsoft’s Azure cloud system to study the technology in a secure environment, FedScoop has learned.

The space agency says it’s taking precautions as it looks to examine possible uses for generative artificial intelligence. Employees looking to evaluate the technology are only invited to join NASA’s generative AI trial if their tests involve “public, non-sensitive data,” Edward McLarney, digital transformation lead for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning at the agency, told FedScoop.

In June, Microsoft announced a new Azure OpenAI tool designed for the government, which according to the company is more secure than the commercial version of the software. Last week, FedScoop reported that the Microsoft Azure OpenAI was approved for use on sensitive government systems. A representative for Microsoft Azure referred to NASA in response to a request for comment. OpenAI did not respond to a request for comment by the time of publication.

There’s no shortage of AI doomsday scenarios to go around, so here’s another AI expert who pretty bluntly forecasts that the technology will spell the death of us all, as reported by Bloomberg.

This time, it’s not a so-called godfather of AI sounding the alarm bell — or that other AI godfather (is there a committee that decides these things?) — but a controversial AI theorist and provocateur known as Eliezer Yudkowsky, who has previously called for bombing machine learning data centers. So, pretty in character.

“I think we’re not ready, I think we don’t know what we’re doing, and I think we’re all going to die,” Yudkowsky said on an episode of the Bloomberg series “AI IRL.”

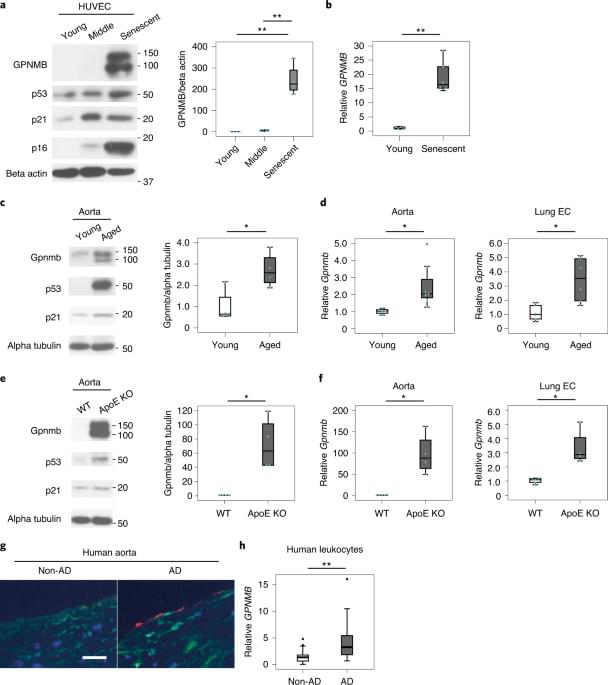

UK scientists have begun developing vaccines as an insurance against a new pandemic caused by an unknown “Disease X”.

The work is being carried out at the government’s high-security Porton Down laboratory complex in Wiltshire by a team of more than 200 scientists.

The fear of artificial intelligence is largely a Western phenomenon. It is virtually absent in Asia. In contrast, East Asia sees AI as an invaluable tool to relieve humans of tedious, repetitive tasks and to deal with the problems of aging societies. AI brings productivity gains comparable to the ICT (information and communications technology) revolution of the late 20th century.

China is using AI as an integral part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which brings together different “Industry 4.0” technologies – high-speed (fifth-generation) communications, the Internet of Things (IoT), robotics, etc. Chinese ports unload container ships in 45 minutes, a task that can take up to a week in other countries.

Today’s fear of AI has many parallels to the fear of machines at the end of the 19th century. French textile workers, fearing mechanical weaving would endanger their jobs and devalue their craft, threw their “sabots” (clogs) into weaving machines to render them inoperable. They gave us the word sabotage.

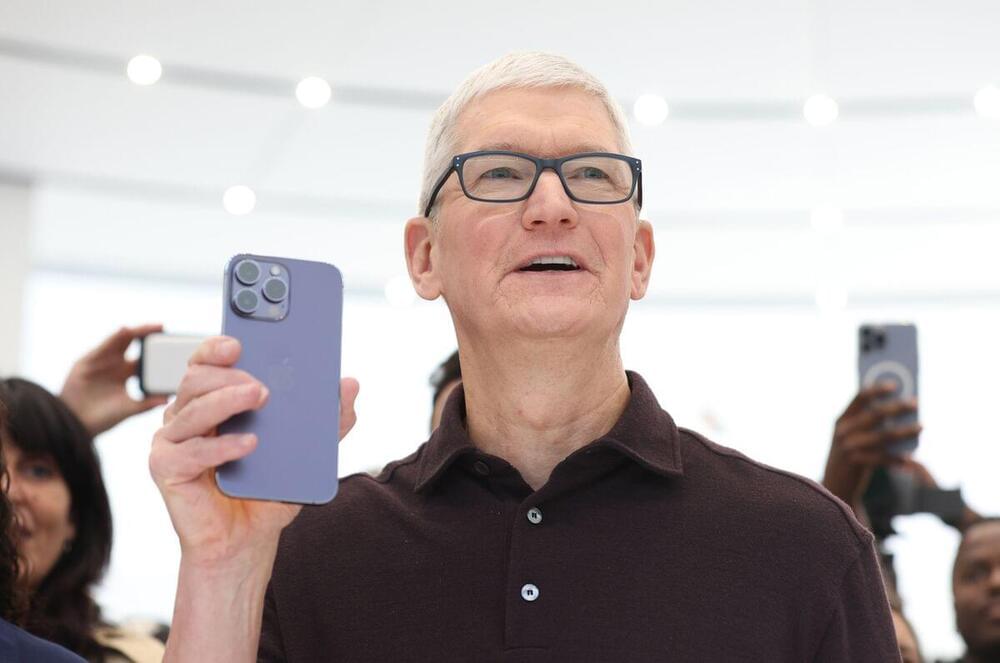

On the cusp of the iPhone 15 debut, Apple has finally admitted what has long been clear: The industry is facing a smartphone slowdown. Also: Another M3 Mac goes into testing, Apple seeks to downplay its Goldman Sachs rift, and Vision Pro developer labs get off to a sluggish start.

Last week in Power On: The iPhone 15 will have thinner bezels in another step toward Apple’s dream phone.