The ‘power couple’ of solar-plus-storage, facilitated by AIoT, will be vital to safeguarding countries’ energy security and reducing geopolitical risks.

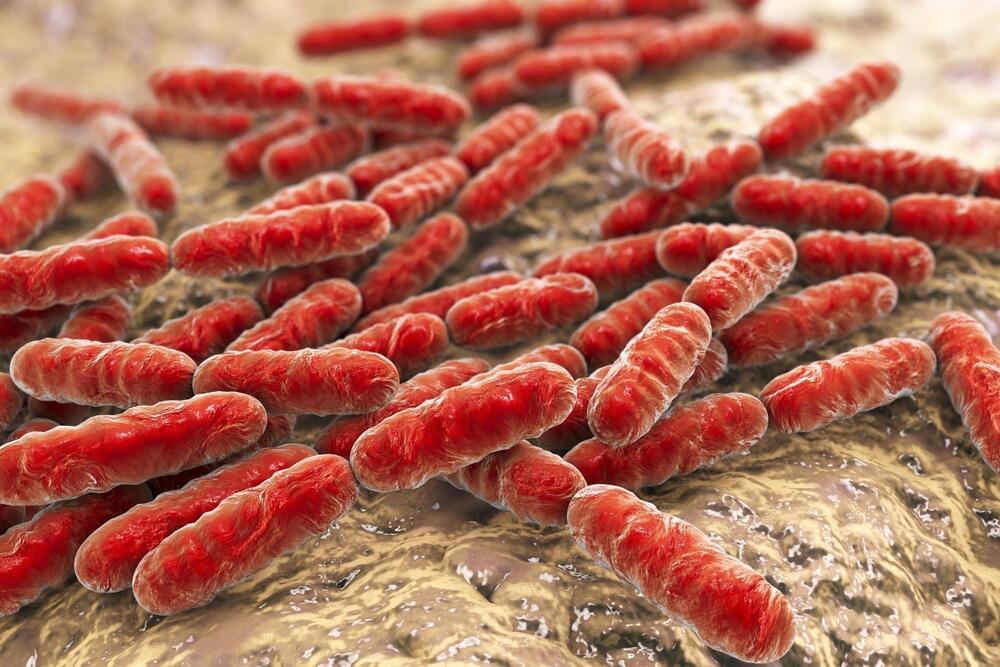

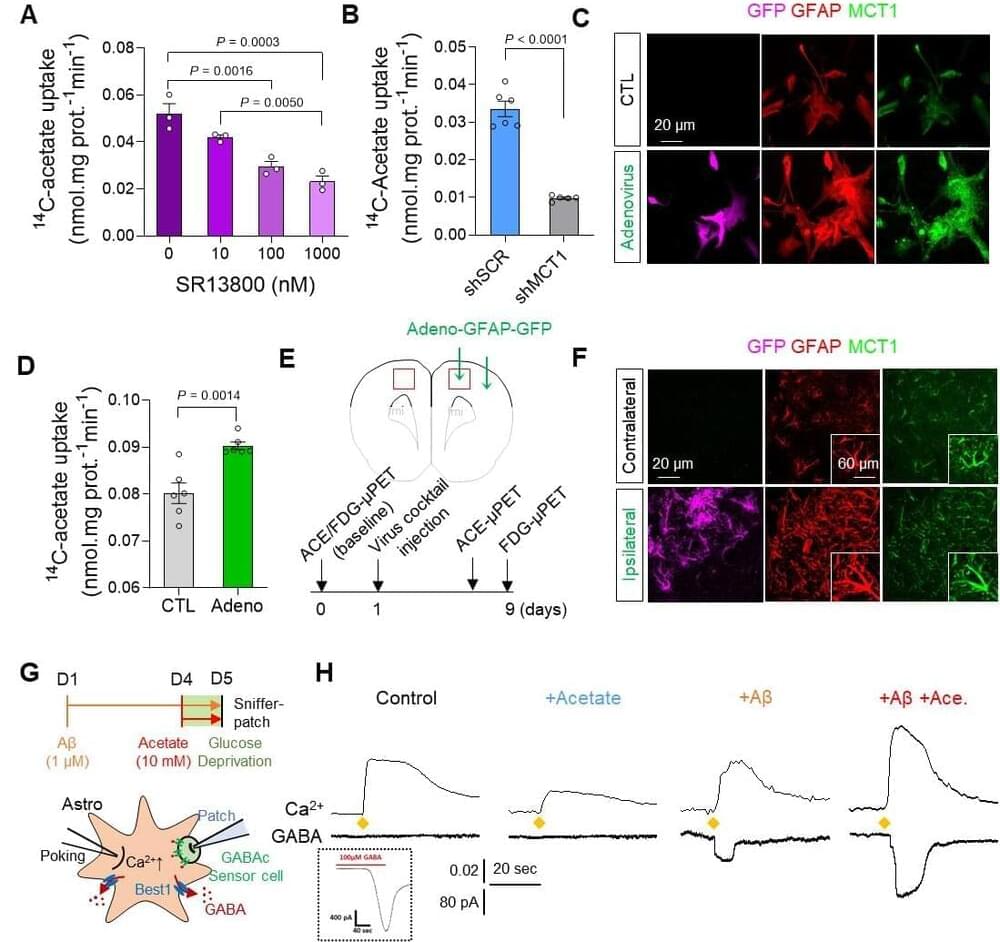

Recently, a team of South Korean scientists led by Director C. Justin Lee of the Center for Cognition and Sociality within the Institute for Basic Science made a discovery that could revolutionize both the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. The group demonstrated a mechanism where the astrocytes in the brain uptake elevated levels of acetates, which turns them into hazardous reactive astrocytes. They then went on to further develop a new imaging technique that takes advantage of this mechanism to directly observe the astrocyte-neuron interactions.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), one of the major causes of dementia, is known to be associated with neuroinflammation in the brain. While traditional neuroscience has long believed that amyloid beta plaques are the cause, treatments that target these plaques have had little success in treating or slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

On the other hand, Director C. Justin Lee has been a proponent of a novel theory that reactive astrocytes are the real culprit behind Alzheimer’s disease. Reactive astrogliosis, a hallmark of neuroinflammation in AD, often precedes neuronal degeneration or death.

In the brains of people without schizophrenia, concepts are organized into specific semantic domains and are globally connected, enabling coherent thought and speech.

In contrast, the researchers reported that the semantic networks of people with schizophrenia were disorganized and randomized. These impairments in semantics and associations contribute to delusion and incoherent speech.

Lithium-ion batteries power our lives.

Because they are lightweight, have high energy density and are rechargeable, the batteries power many products, from laptops and cell phones to electric cars and toothbrushes.

However, current lithium-ion batteries have reached the limit of how much energy they can store. That has researchers looking for more powerful and cheaper alternatives.

Researchers in Carnegie Mellon University’s Robotics Institute (RI) have designed a system that makes an off-the-shelf quadruped robot nimble enough to walk a narrow balance beam—a feat that is likely the first of its kind.

“This experiment was huge,” said Zachary Manchester, an assistant professor in the RI and head of the Robotic Exploration Lab. “I don’t think anyone has ever successfully done balance beam walking with a robot before.”

To the team’s knowledge, this is the first instance of a quadruped successfully walking on a narrow balance beam. Their paper, “Enhanced Balance for Legged Robots Using Reaction Wheels,” was accepted to the 2023 International Conference on Robotics and Automation. The annual conference will be held May 29–June 2, in London.