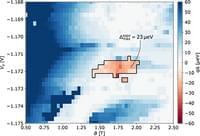

For the first time, researchers using pulsar timing arrays have found evidence for the long-sought-after gravitational wave background. Though the exact source of this low-frequency gravitational wave hum is not yet known, further observations may reveal it to be from pairs of supermassive black holes orbiting one another or from entirely new physics at work in our universe.

A New Window onto Gravitational Waves

In 2016, researchers reported the first detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), opening a new window onto a universe’s worth of collisions between extreme objects like black holes and neutron stars. Though this discovery marked the beginning of a new observational era, many sources of gravitational waves remained beyond the reach of our current detectors on Earth.