AI is going to have a huge impact on the workforce. And while there will be winners in the workplace, there will also be losers.

Since 2015, reusable rockets have dramatically decreased the cost of transportation from Earth to orbit. Such process is paving the path toward a civilian sp…

Summary: Researchers developed a machine learning algorithm, FoodProX, capable of predicting the degree of processing in food products.

The tool scores foods on a scale from zero (minimally or unprocessed) to 100 (highly ultra-processed). FoodProX bridges gaps in existing nutrient databases, providing higher resolution analysis of processed foods.

This development is a significant advancement for researchers examining the health impacts of processed foods.

Is Senior Vice President of the Energy Systems business unit of Westinghouse Electric Company, which is the nuclear power unit of.

Westinghouse, where her core focus is in leading the team developing and.

deploying their AP300 Small Modular Nuclear Reactor (https://www.westinghousenuclear.com/Portals/0/about-2020/lea…UL22.pdf).

Dr. Baranwal recently served Chief Technology Officer of the organization, where she led the company’s global research and development investments, spearheading their technology strategy to advance the company’s nuclear innovation, and drove next-generation solutions for existing and new markets.

Dr. Baranwal’s appointment to this CTO role in 2022 marked a return to Westinghouse where she worked for nearly a decade in leadership positions in the Global Technology Development, Fuel Engineering, and Product Engineering groups.

Prior to rejoining Westinghouse, Dr. Baranwal served as Assistant Secretary for the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Nuclear Energy where she directed the R&D portfolio across current and advanced nuclear technologies while collaborating across nuclear utilities, national labs, reactor developers, academia and government stakeholders. She has also held senior leadership roles with the Idaho National Laboratory as Director of the Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear (GAIN), and most recently was the Chief Nuclear Officer and Vice President of Nuclear for the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI).

Prior to joining Westinghouse, Dr. Baranwal was a manager in Materials Technology at Bechtel Bettis, Inc. where she led and conducted R&D in advanced nuclear fuel materials for US Naval Reactors.

Dr. Baranwal is a Fellow of the American Nuclear Society. She has a bachelor’s degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in materials science and engineering and a master’s degree and Ph.D. in the same disciplines from the University of Michigan.

The system demonstrated its chops on Kepler’s third law of planetary motion, Einstein’s relativistic time-dilation law, and Langmuir’s equation of gas adsorption.

AI-Descartes, a new AI scientist, has successfully reproduced Nobel Prize-winning work using logical reasoning and symbolic regression to find accurate equations. The system is effective with real-world data and small datasets, with future goals including automating the construction of background theories.

In 1918, the American chemist Irving Langmuir published a paper examining the behavior of gas molecules sticking to a solid surface. Guided by the results of careful experiments, as well as his theory that solids offer discrete sites for the gas molecules to fill, he worked out a series of equations that describe how much gas will stick, given the pressure.

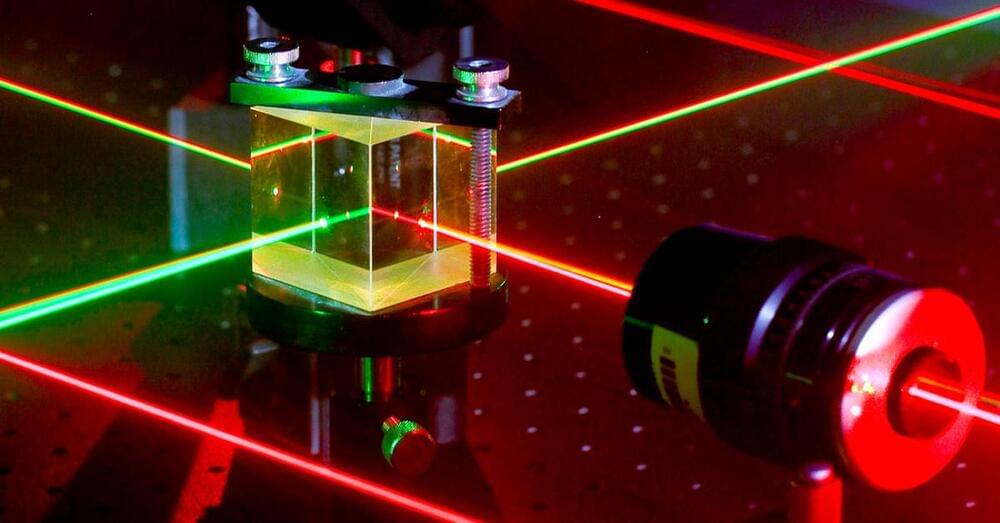

Finding practical applications for quantum entanglement is a formidable endeavor to say the least, but a group of Chinese researchers overcame some of the fundamental challenges of open-air quantum teleportation by developing a highly accurate laser pointing and tracking system, as reported by Ars Technica. The team was able to teleport a qubit (a standard unit of data in quantum computing) 97 kilometers across a lake using a small set of photons without fiberoptic cables or other intermediaries.

The laser targeting device developed by Juan Yin and his team was necessary to counteract the minute seismic and atmosphere shifts that would otherwise break the link between the two remote locations. While the use of fiberoptic cables solves the point-to-point accuracy problems faced by open-air systems, using the cables to carry entangled photons — which in turn carry the data needed for quantum teleportation — can cause what’s known as “quantum decoherence,” or rather a corruption in the photon’s entanglement data.

In the grand spectrum of scientific achievement, Yin’s research is a small but crucial stepping stone on the path to a global quantum network, allowing for super-fast data transmission with high levels of encryption to take place. Yin and his team think that quantum repeater satellites could be used to build this network, but until scientists figure out a way to give qubits a few more microseconds of staying power, such a network is probably many years off.

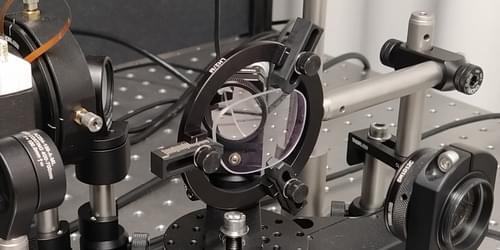

A new device can recreate the refractive errors of a myopic eye—one that displays nearsightedness—allowing scientists to test lenses designed to slow down the progression of the condition.

A team of researchers including Augusto Arias-Gallego at the University of Tübingen, Germany, has developed a device for mimicking the refractive errors of a nearsighted eye [1]. The team demonstrates the ability of this “artificial eye” to characterize the real-world performance of eyeglasses designed to slow the worsening of the condition in children. The team hopes that the insight gained with their system will aid in the development of more effective iterations of a potentially sight-saving technology. “By characterizing the prototype lenses in the lab, we can easily check if the designs are good candidates to slow myopia progression,” Arias-Gallego says. “That could help millions of children.”

Poor eyesight is on the rise. Today, one third of the world’s population suffers from some form of visual impairment, up from one fifth a decade ago. By 2050, estimates indicate that the fraction will increase to over one in two. The most common vision condition is nearsightedness, also known as myopia, which leads moderate sufferers unable to resolve objects more than a few feet away. When left untreated myopia can develop into sight-threatening conditions such as retinal detachment.

Year 2020 o.o!!!

The primary difficulty of interstellar communication is finding common ground between ourselves and other intelligent entities about which we can know nothing with absolute certainty. This common ground would be the basis for a universal language that could be understood by any intelligence, whether in the Milky Way, Andromeda, or beyond the cosmic horizon. To the best of our knowledge, the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe, which suggests that the facts of science may serve as a basis for mutual understanding between humans and an extraterrestrial intelligence.

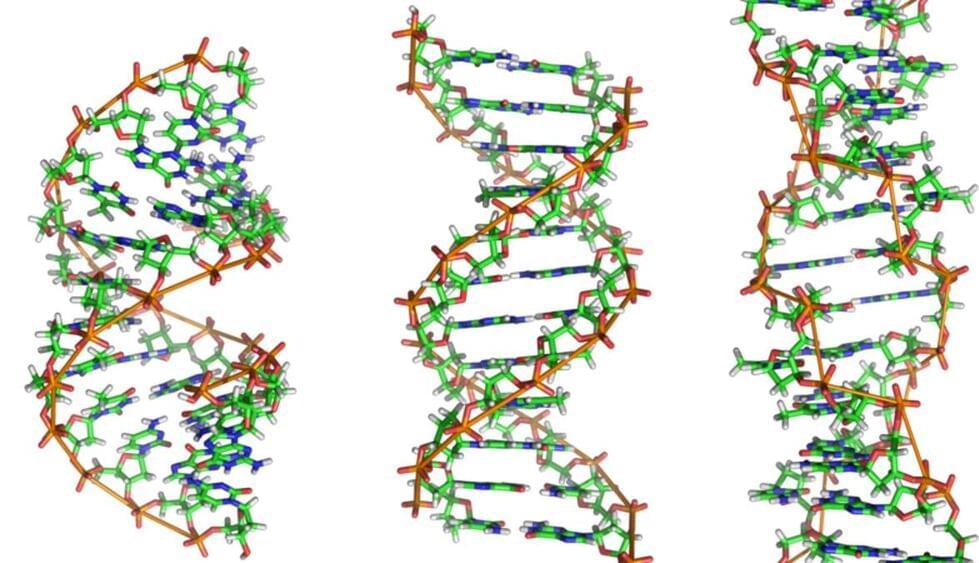

One key set of scientific facts presents an intriguing question. If aliens were to visit Earth and learn about its inhabitants, would they be surprised that such a wide variety of species all share a common genetic code? Or would this be all too familiar? There is probable cause to assume that the structure of genetic material is the same throughout the universe and that, while this is liable to give rise to life forms not found on Earth, the variety of species is fundamentally limited by the constraints built into the genetic mechanism.

On Earth we have only sequenced the genomes of a small percentage of living organisms and have only recently completed the human genome. We have successfully cloned several animals, but technical and ethical roadblocks prevent scientists from doing the same with humans. If an extraterrestrial civilization isn’t burdened with ethical dilemmas about cloning, however, sending the genetic code for humans and other species may be the most effective way to teach them about our biology.