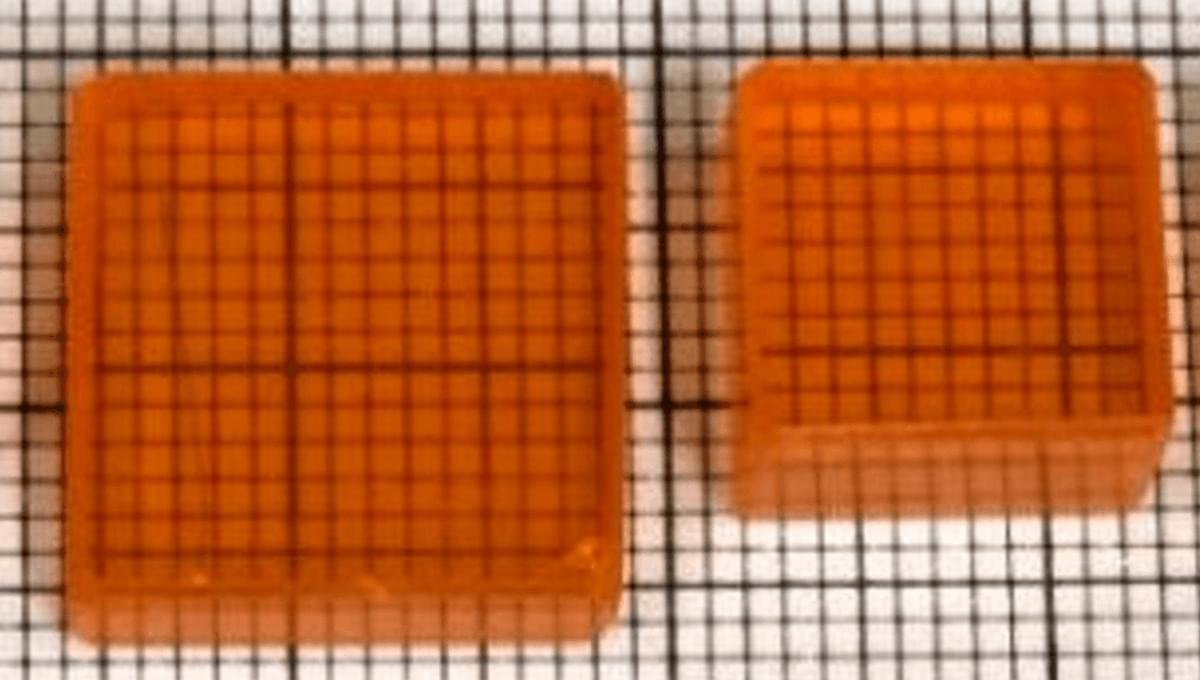

For the first time, lab-grown mini brains have revealed how neurons misfire in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

To learn for free on Brilliant, go to https://brilliant.org/mattbatwings/

You’ll also get 20% off an annual premium subscription.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/mattbatwings.

Discord: https://discord.gg/V5KFaF63mV

My socials: https://linktr.ee/mattbatwings.

My texture pack: https://modrinth.com/resourcepack/mattpack.

World Download: (JAVA 1.21.4) https://www.planetminecraft.com/project/redstone-powder-simulation/

Powder Pack: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_Ec7NOa_Dou_NKmCX-EbEDT-y6p…sp=sharing.

Powder Sims used in this video:

https://dan-ball.jp/en/javagame/dust2/

https://sandboxels.r74n.com/

Thank you again @bratworst for all your help! His powder sim: https://youtu.be/FUlX9AomkU8

Thumbnail made by @Activation123

See my Comment below for a link to David Orban’s 20 minute talk.

In this keynote, delivered at The Futurists X Summit, on September 22 in Dubai, David Orban maps how AI and humanoid robotics shift us from steady exponential progress to an acceleration of acceleration—what he calls the Jolting Technologies Hypothesis. He argues we’re not in a zero-sum economy; as capability compounds and doubling times shrink, we unlock new degrees of freedom for individuals, firms, and society. The challenge is to steer that power with clear narratives, robust safety, and deliberate design of work, value, and purpose.

You’ll hear:

• Why narratives (optimism vs. doom) shape which futures become real.

• How shortening doubling times in AI capabilities pull forward timelines once thought 20–30 years out.

• Why trust in AI is task-relative: if +5% isn’t enough, aim for 10× reliability.

• The coming phase transformation as intelligence becomes infrastructure (homes, mobility, industry).

• Concrete social questions (e.g., organ donation post–road-death decline) that demand AI-assisted governance.

• Why the nature of work will change: from jobs as status to human aspiration as value.

Key ideas:

• Humanoid robots at scale: rapid iteration, non-fragile recovery, and human-complementary performance.

• Designing agency: go from idea → action with near-instant execution; experiment, learn, and iterate fast.

• From zombies to luminaries: use newfound freedom to architect lives worth living.

Resources & Links:

In an article published in Communications Physics, researchers from the Université libre de Bruxelles and the Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information in Vienna present a new framework for describing physics relative to quantum reference frames, unveiling the importance of previously unrecognized “extra particles.”

In any experiment, specifying a physical quantity of interest always relies on a reference frame. For example, identifying the time at which an event happens only makes sense relative to a clock. Similarly, the position of a particle is usually defined relative to other particles. Reference frames are typically treated as classical systems, that is, they are assumed to have definite values when measured relative to other reference frames.

However, as far as we know, every system is ultimately quantum. As such, it can, in principle, exist in indefinite states called quantum superpositions. What does the physical world look like when described from the perspective of a reference frame that can be in a quantum superposition? Can we define consistent rules for changing between different perspectives?

Alabama spacecraft manufacturer Quantum Space is already putting its $40M Series A extension round to work, announcing the acquisition of Phase Four’s multi-modal propulsion tech on Monday for an undisclosed amount.

Quantum has also taken over ownership of Phase Four’s integration and test facility in Hawthorne, CA, which can churn out up to 100 engines per year.

Paying in gold: The deal opens the door for Quantum to integrate Phase Four’s unique propulsion capabilities to fuel Quantum’s Golden Dome ambitions. Phase Four’s multi-modal propulsion system uses chemical and electric propulsion to perform high thrust or high efficiency maneuvers, depending on the mission.

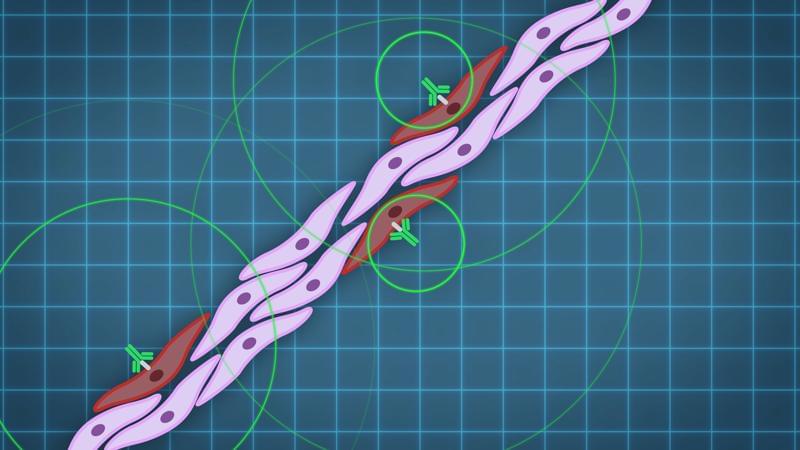

An unusual therapy developed at The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) could change the way the world fights influenza, one of the deadliest infectious diseases. In a new study in Science Advances, researchers report that a cocktail of antibodies protected mice—including those with weakened immune systems—from nearly every strain of influenza tested, including avian and swine variants that pose pandemic threats.

Unlike current FDA-approved flu treatments, which target viral enzymes and can quickly become useless as the virus mutates, this therapy did not allow viral escape, even after a month of repeated exposure in animals. That difference could prove crucial in future outbreaks, when survival often depends on how quickly and effectively doctors can deploy treatments and vaccine development will take about six months.

“This is the first time we’ve seen such broad and lasting protection against flu in a living system,” said Silke Paust, an immunologist at JAX and senior author of the study. “Even when we gave the therapy days after infection, most of the treated mice survived.”

Physician-scientist David Fajgenbaum was dying from a rare disease that didn’t have a cure — until he discovered a lifesaving drug that wasn’t originally intended for his condition. In an astonishing talk, he shares how his near-death experience led him to cofound the nonprofit Every Cure, which is using AI to uncover hidden treatments in existing medicines in order to save lives. (This ambitious idea is part of The Audacious Project, TED’s initiative to inspire and fund global change.)

When it comes to their survival, cancer cells have a host of backup plans.

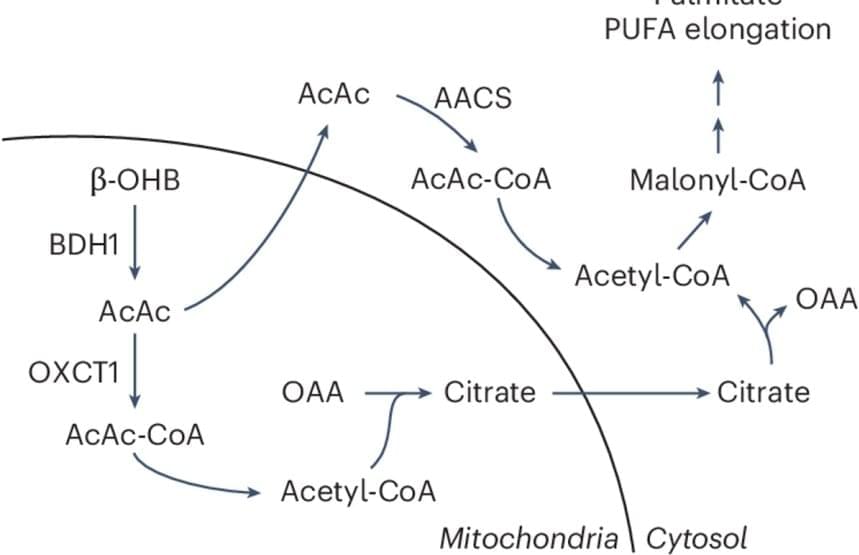

This is especially true of the nutrients that cancers use to grow and spread. In addition to relying on sugars like glucose to power their proliferation, some cancer cells also use ketones — metabolites produced from fats when the body is fasting or on a low carb diet — as an alternate fuel source.

Now, a new study scientists suggest that the routes cancer cells use to process these different nutrients deeply influence cell behavior. They discovered an alternate, or non-canonical, path by which cancer cells convert a ketone called β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) into acetyl-CoA, an essential metabolic building block for fatty acids and cholesterol that supports cell proliferation.

The findings, published in the journal Nature Metabolism, could reshape how the relationship between diet and cancer is viewed.

The authors also found that cancer cells can leverage this alternative β-OHB pathway even when glucose, the body’s main source of energy, is plentiful. This suggests that, depending on the circumstances, glucose may not always be the nutrient of choice for cells.