If it has seemed like more people you know are developing diabetes, you are right. The diabetes epidemic is not called an epidemic for nothing: According to the American Diabetes Association, over 10% of the U.S. population—approximately 38.4 million people—had diabetes in 2021, and 1.2 million more people get diagnosed each year.

Type 2 diabetes occurs when your body develops a resistance to insulin, the hormone that helps regulate glucose levels in your blood. Insulin is secreted by pancreatic cells called β-cells, and in T2D, they ramp up insulin production to try to regulate blood glucose levels, but even that is insufficient and the β-cells eventually become exhausted over time. Thanks to their importance, the functional β-cell mass, or the total number of β-cells and their function, determines a person’s risk of diabetes.

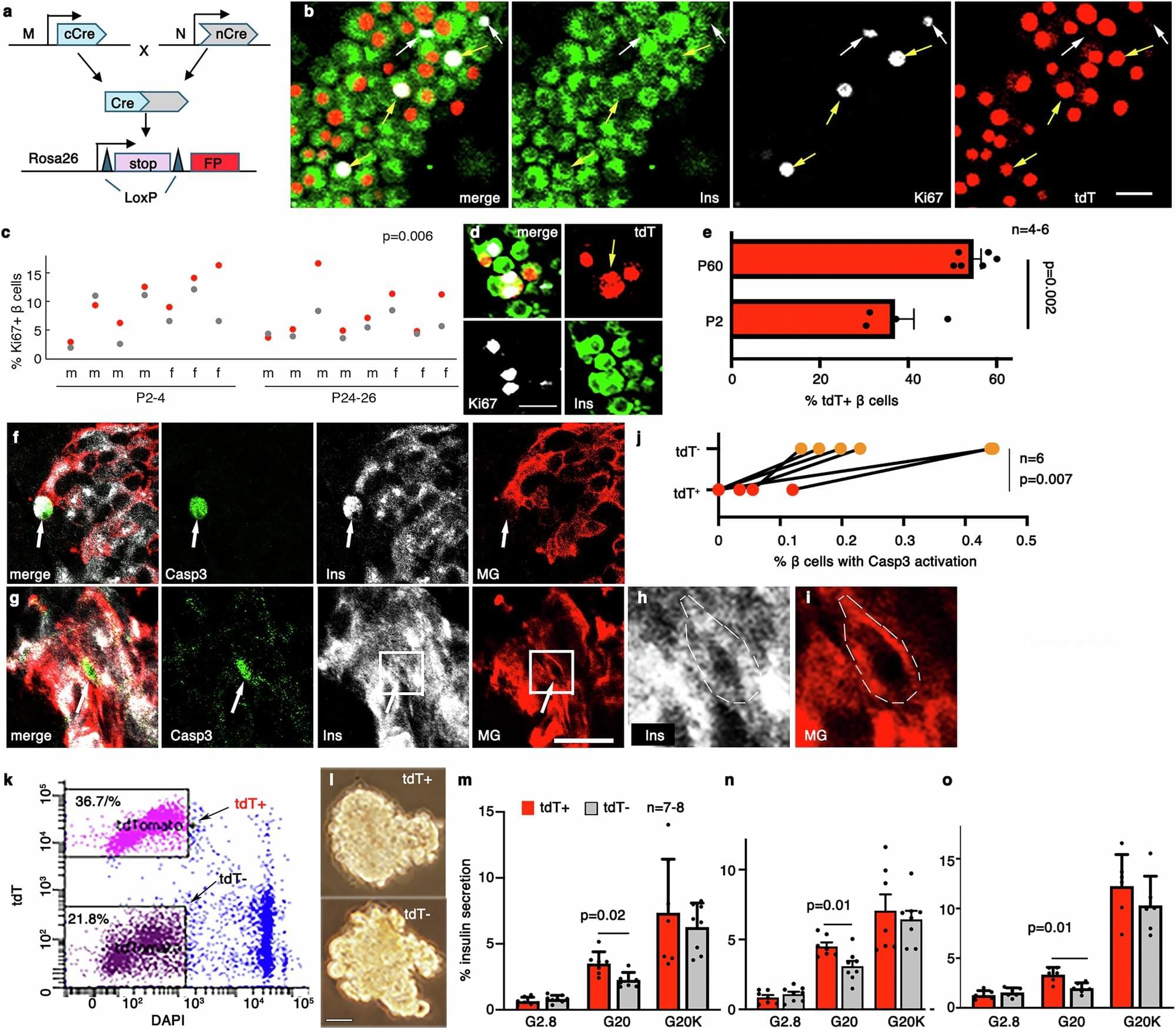

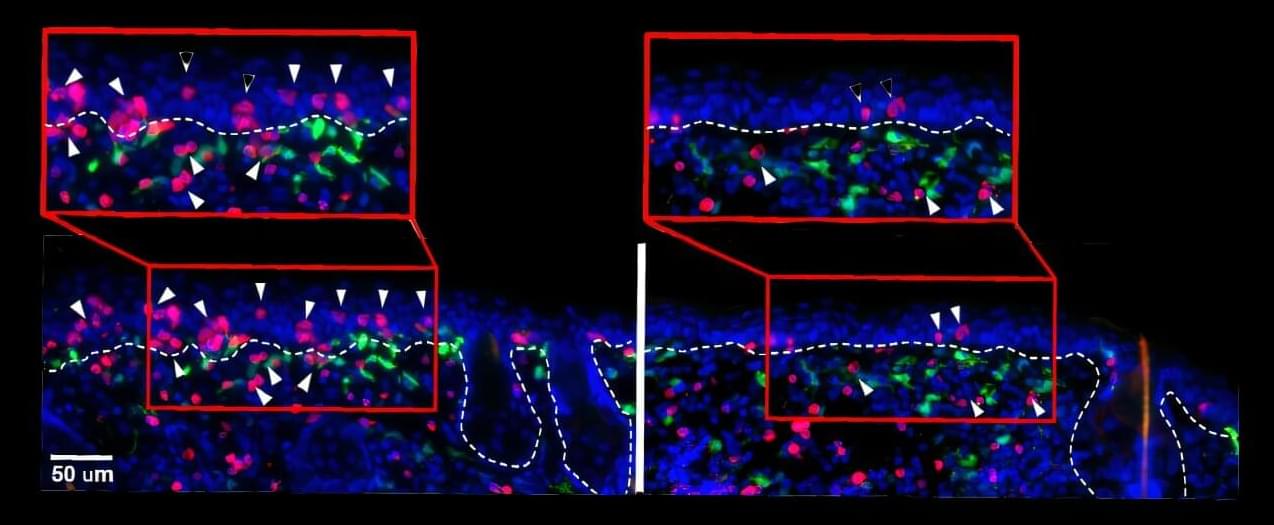

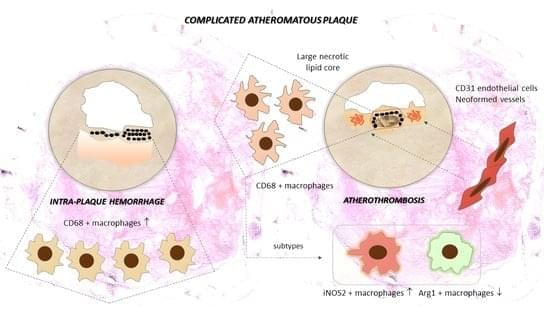

Β-cells are not homogeneous, even within a single individual, and consist of different “subtypes,” each with their own secretory function, viability, and ability to divide. In other words, each β-cell subtype has a different level of fitness, and the higher, the better. When diabetes develops, the proportions of some β-cell subtypes are changed. But a key question remains: Are the proportion and fitness of different β-cell subtypes altered by diabetes or are the changes responsible for the disease?