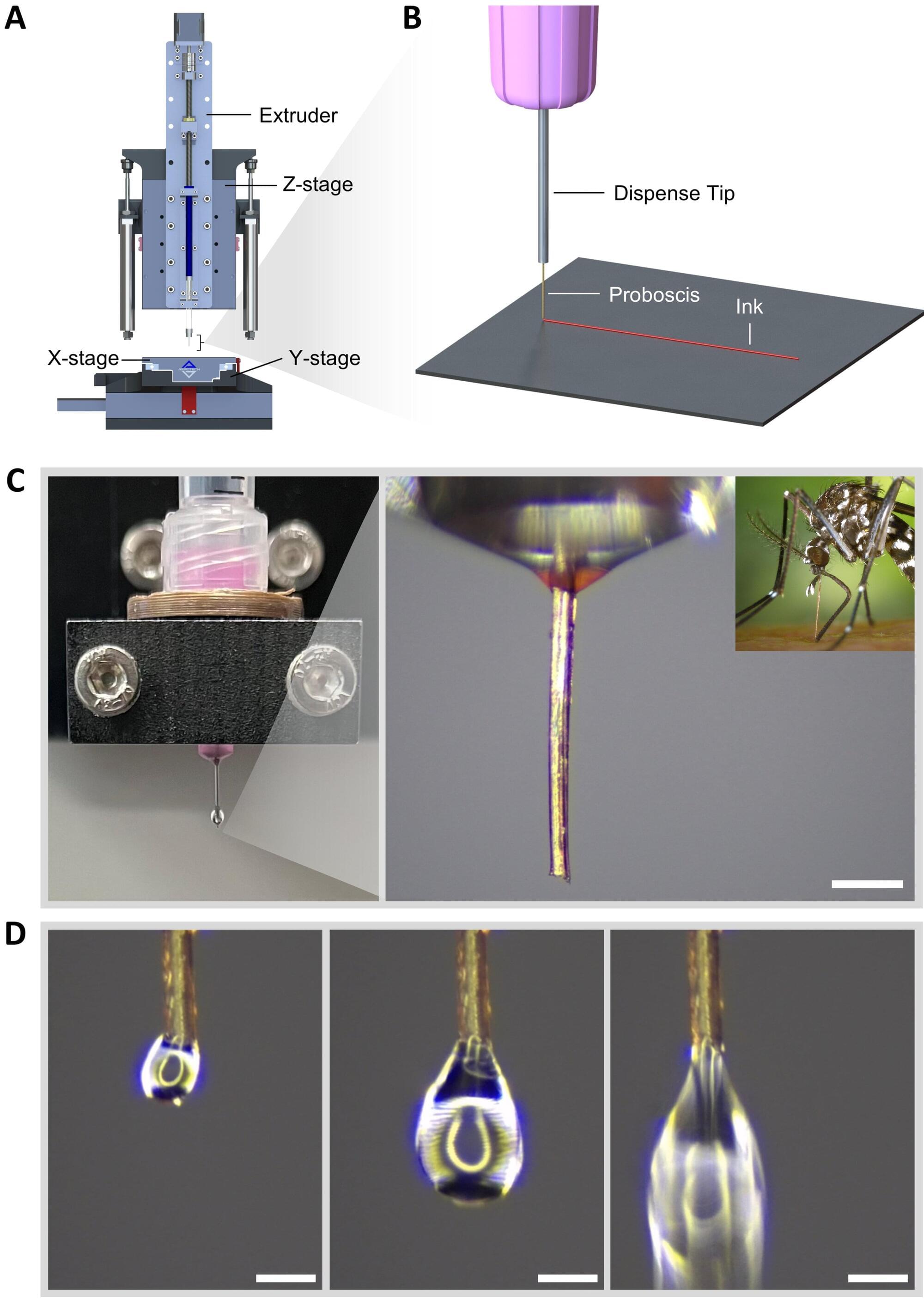

When it comes to innovation, engineers have long proved to be brilliant copycats, drawing inspiration directly from nature. But now some scientists are moving beyond simple imitation to incorporating natural materials into their designs. Stuck for ideas on how to create ultra-fine, low-cost 3D printing nozzles, researchers at McGill University in Canada repurposed the proboscis of a deceased female mosquito to create a sustainable, high-resolution 3D printing tip.

The work is published in the journal Science Advances.

High-resolution 3D printing is a process that creates three-dimensional objects with extremely fine details and very smooth surfaces. The technology is used in numerous fields such as aerospace, dentistry and biomedical research. However, its level of precision comes at a steep cost. The tiny nozzles can cost more than $80 per tip and are made of metal or plastic, both of which are nonbiodegradable.