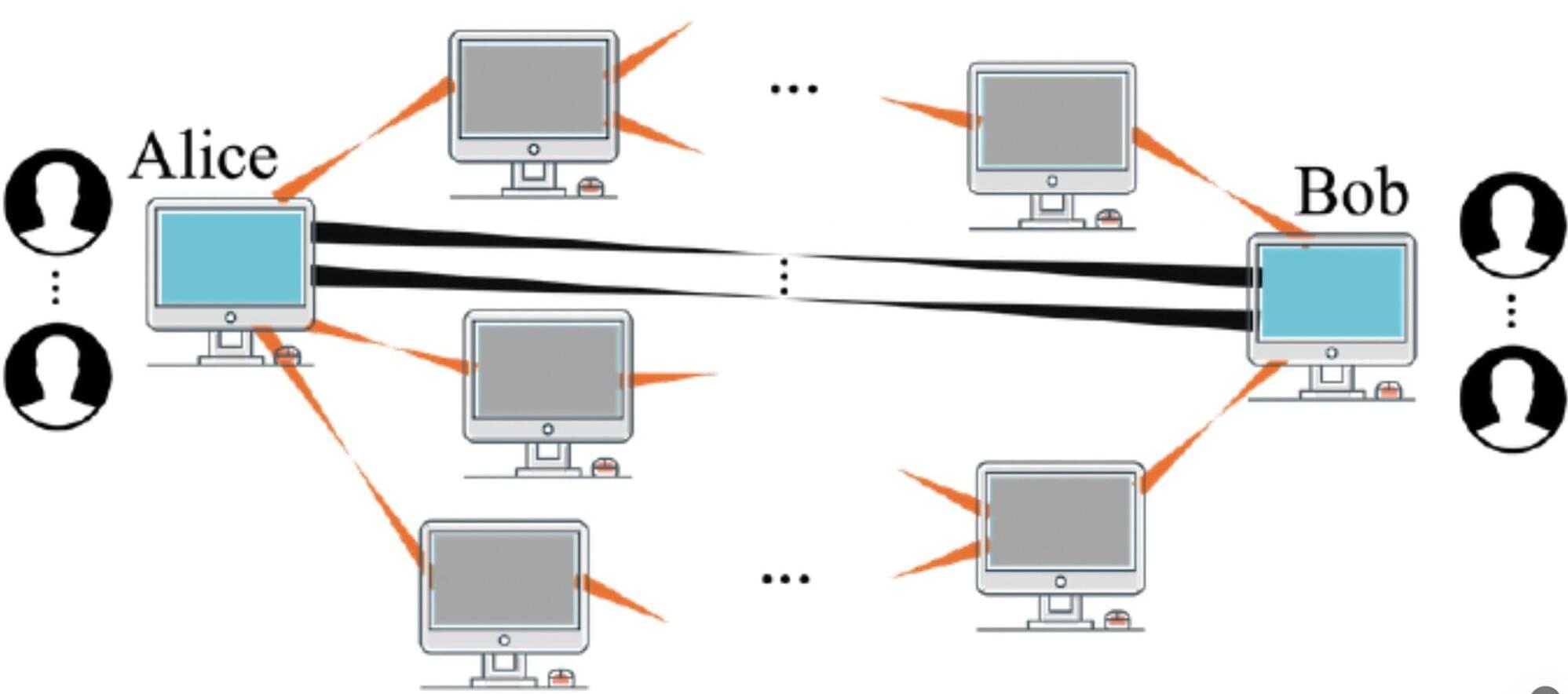

Quantum technologies, systems that process, transfer or store information leveraging quantum mechanical effects, could tackle some real-world problems faster and more effectively than their classical counterparts. In recent years, some engineers have been focusing their efforts on the development of quantum communication systems, which could eventually enable the creation of a “quantum internet” (i.e., an equivalent of the internet in which information is shared via quantum physical effects).

Networks of quantum devices are typically established leveraging quantum entanglement, a correlation that ensures that the state of one particle or system instantly relates to the state of another distant particle or system. A key assumption in the field of quantum science is that greater entanglement would be linked to more reliable communications.

Researchers at Northwestern University recently published a paper in Physical Review Letters that challenges this assumption, showing that, in some realistic scenarios, more entanglement can adversely impact the quality of communications. Their study could inform efforts aimed at building reliable quantum communication networks, potentially also contributing to the future design of a quantum internet.