(TGA) is a syndrome of sudden, reversible anterograde and shrinking retrograde amnesia, typically lasting several hours for which the etiology remains obscure.

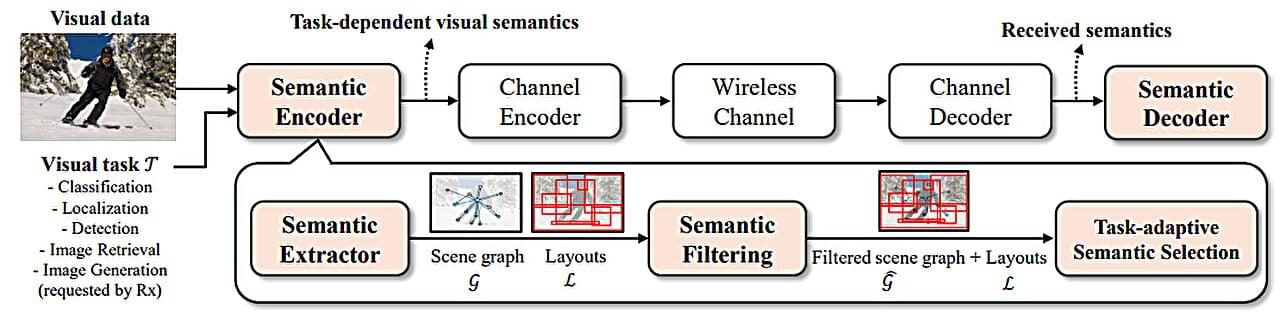

A new AI-driven technology developed by researchers at UNIST promises to significantly reduce data transmission loads during image transfer, paving the way for advancements in autonomous vehicles, remote surgery and diagnostics, and real-time metaverse rendering—applications that demand rapid, large-scale visual data exchange without delay.

Led by Professor Sung Whan Yoon from the Graduate School of Artificial Intelligence at UNIST, the research team developed Task-Adaptive Semantic Communication, an innovative wireless image transmission method that selectively transmits only the most essential semantic information relevant to the specific task. Their study is published in the IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications.

Current wireless image transmission methods compress entire images without considering their underlying semantic structures—such as objects, layout, and relationships—resulting in bandwidth limitations and transmission delays that hinder real-time high-resolution image sharing.

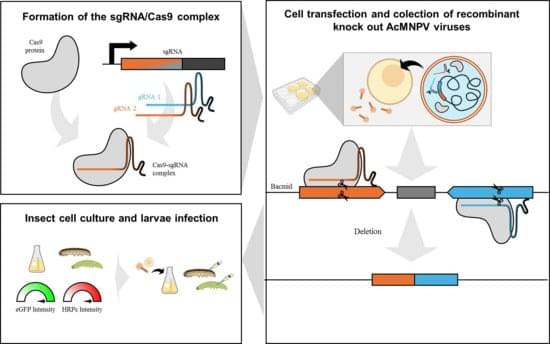

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a powerful genome-editing tool that is applied in baculovirus engineering. In this study, we present the first report of the AcMNPV genome deletions for bioproduction purposes, using a dual single-guide RNA (sgRNA) CRISPR/Cas9 approach. We used this method to remove nonessential genes for the budded virus and boost recombinant protein yields when applied as BEVS. We show that the co-delivery of two distinct ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, each assembled with a sgRNA and Cas9, into Sf9 insect cells efficiently generated deletions of fragments containing tandem genes in the genome. To evaluate the potential of this method, we assessed the expression of two model proteins, eGFP and HRPc, in insect cells and larvae. The gene deletions had diverse effects on protein expression: some significantly enhanced it while others reduced production.

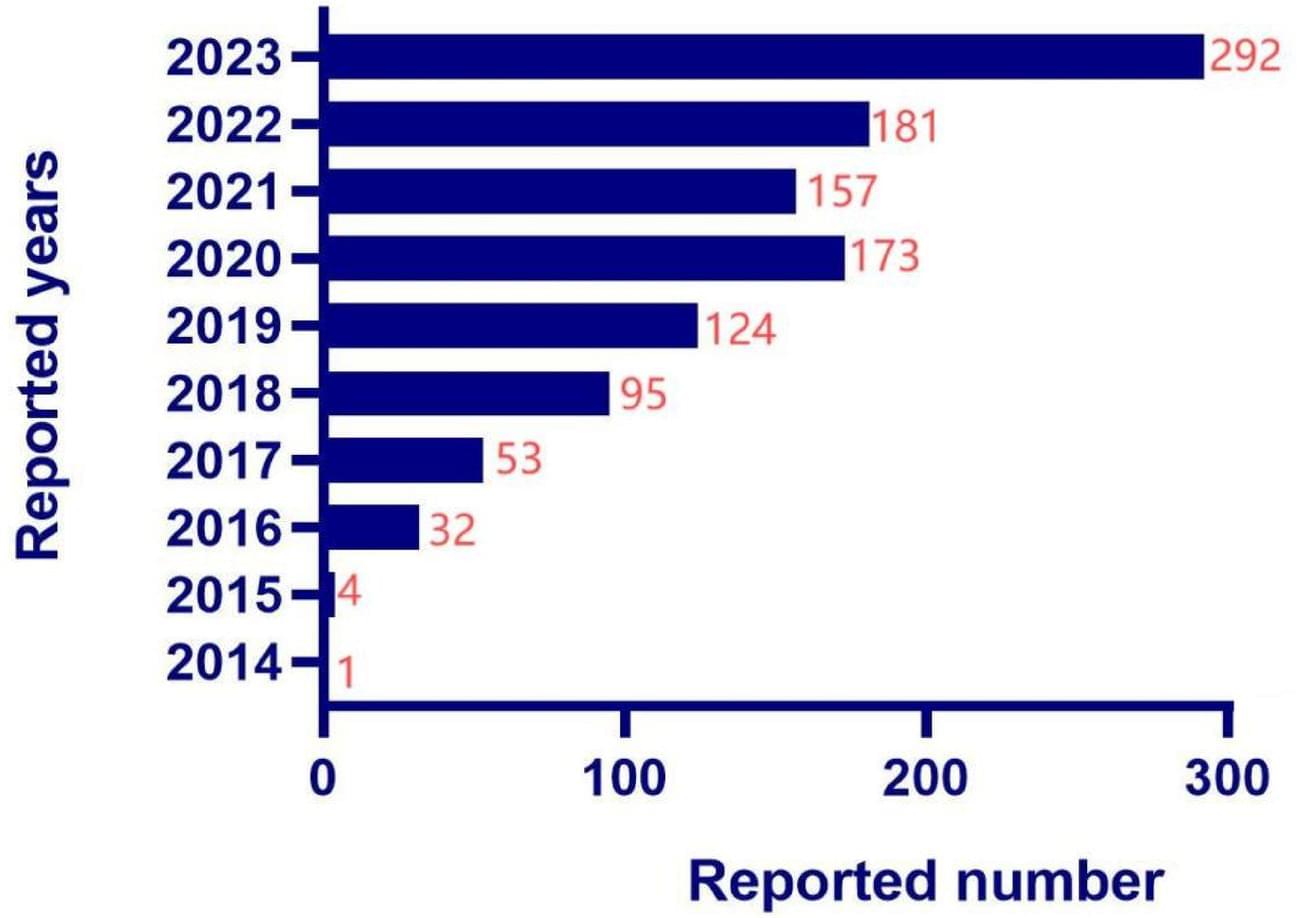

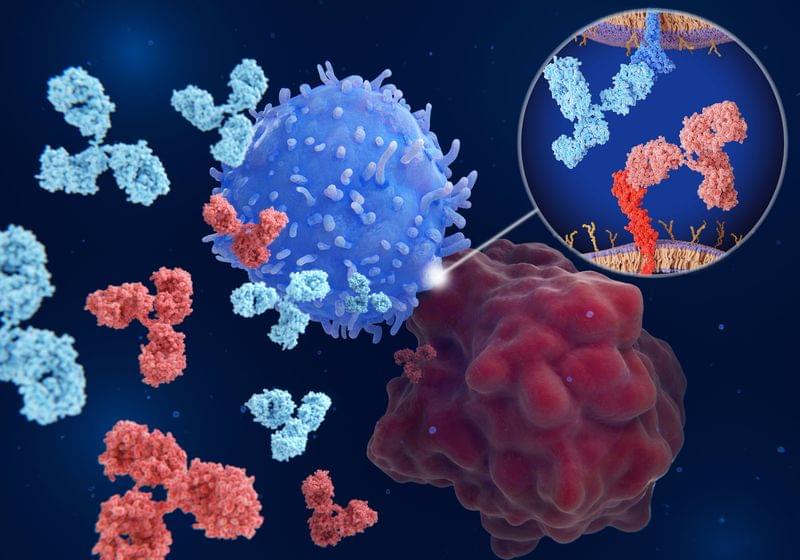

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are medications used in cancer immunotherapy. However, treatment with ICIs may lead to adverse effects, particularly myocarditis and pericarditis. This practical pharmacovigilance study investigates the relationship between ICIs and myocarditis and pericarditis using the FAERS (U.S. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) database.

Data on myocarditis and pericarditis related to ICIs were extracted from the FAERS database for the period from 2014Q1 to 2023Q4. Data mining was performed using the Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network (BCPNN) and the Reporting Odds Ratio (ROR).

A total of 1,112 cases involving 1,134 adverse event (AE) reports related to ICIs-associated noninfectious myocarditis/pericarditis (NM/P) were extracted from the FAERS database. After excluding reports with missing data, the primary reporters were physicians, consumers, and pharmacists, with the United States and Japan being the main reporting countries. The cases showed a greater percentage of males than females, with a median age of 67 years, a median weight of 65 kg, and a median onset time of 28 days. The signal strength of ICIs-associated NM/P, from highest to lowest, was as follows: Pembrolizumab (ROR: 12.32, 95% CI: 11.28–13.45, IC 025: 3.45) Nivolumab (ROR: 11.23, 95% CI: 10.13–12.44, IC 025: 3.30) Atezolizumab (ROR: 10.62, 95% CI: 8.67–13.02, IC 025: 3.10) Ipilimumab (ROR: 10.25, 95% CI: 8.34–12.58, IC 025: 3.04) Durvalumab (ROR: 9.25, 95% CI: 7.21–11.88, IC 025: 2.83).

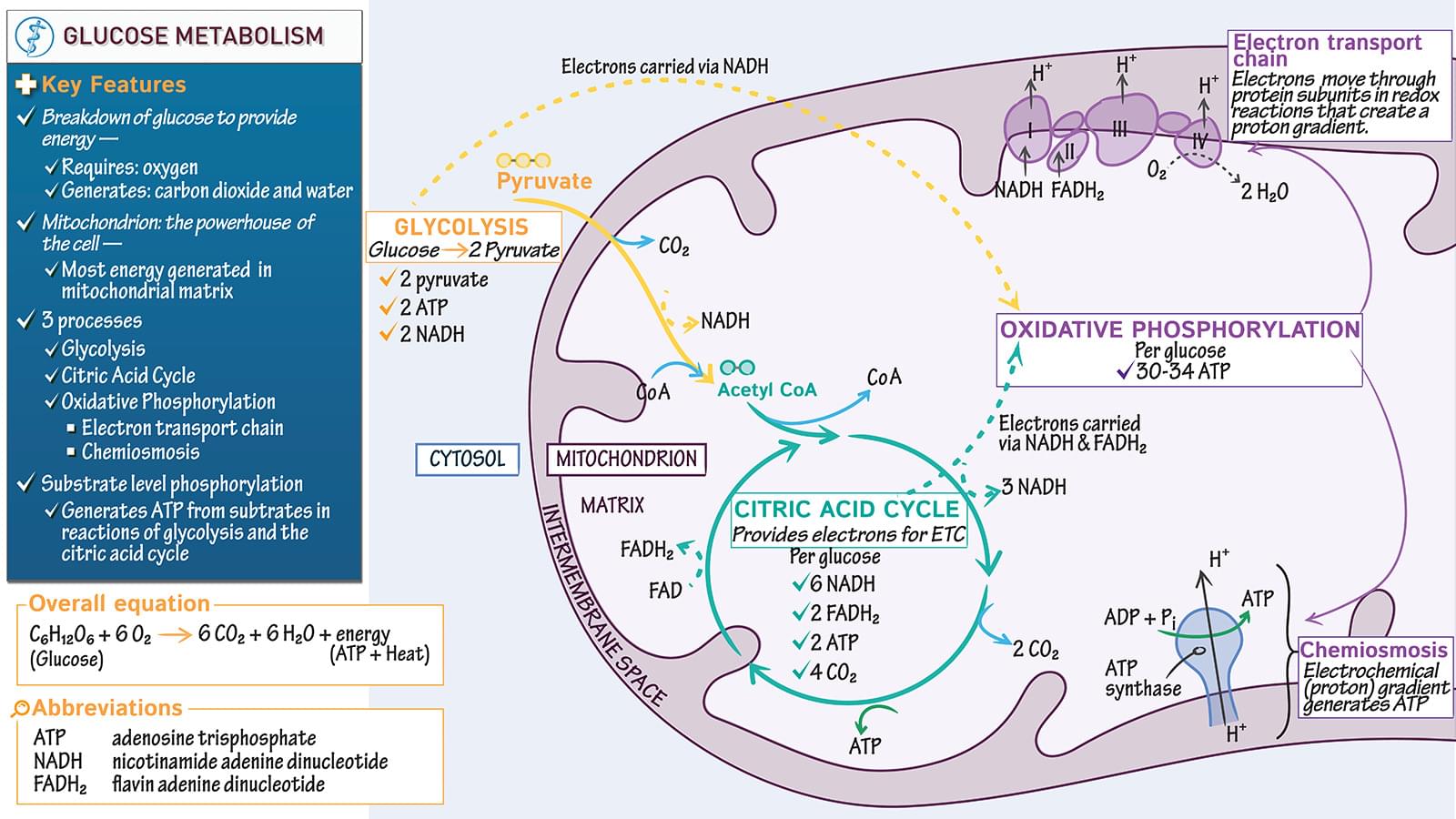

GLUCOSE OXIDATION EQUATION Glucose + 6 O2 — 6 CO2 + 6 H2O + Energy (ATP + heat) • Most energy is generated in mitochondrial matrixCommon Abbreviations: • ATP: adenosine triphosphate • NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide • FADH2: flavin adenine dinucleotide • CoA: Coenzyme AKEY PROCESSES IN GLUCOSE OXIDATION • Glycolysis • Pyruvate decarboxylation • Citric acid cycle (also known as the Krebs’ cycle and the tri-carboxylic acid (TCA) cycle) • Oxidative phosphorylation (electron transport chain & chemiosmosis)CITRIC ACID CYCLE • 1 glucose molecule requires 2 citric acid cycle turns • Input for each turn: 1 Acetyl CoA • Output for each turn: 3 NADH + 2 CO2 + 1 ATP + 1 FADH2 • NADH & FADH2: electron transfer molecules for oxidative phosphorylation • Occurs in mitochondrial matrixSubstrate level phosphorylation • ATP generated from substrates in glycolysis and citric acid cycle • NOT from.

Sewage sludge isn’t just waste, it can be a hotspot for antimicrobial resistance.

This study on @FEMSmicrobes uncovers multidrug-resistant bacteria, high AMR-gene abundance, and metal-tolerant strains in STP sludge, highlighting why environmental screening is crucial for AMR control.

STP sludge study reveals diverse drug-resistant bacteria harboring ARGs, stressing screening to curb AMR and environmental risks.

Emerging trends in the disassembly of stress granules and P-bodies.

Stress granules (SGs) and P-bodies (PBs) are dynamic RNA-protein condensates regulating mRNA fate. While assembly mechanisms are well studied, emerging insights into their dissolution are now coming to light. Here, Garg et al. highlight the current understanding of disassembly mechanisms and their implications in neurodegeneration and cancer.