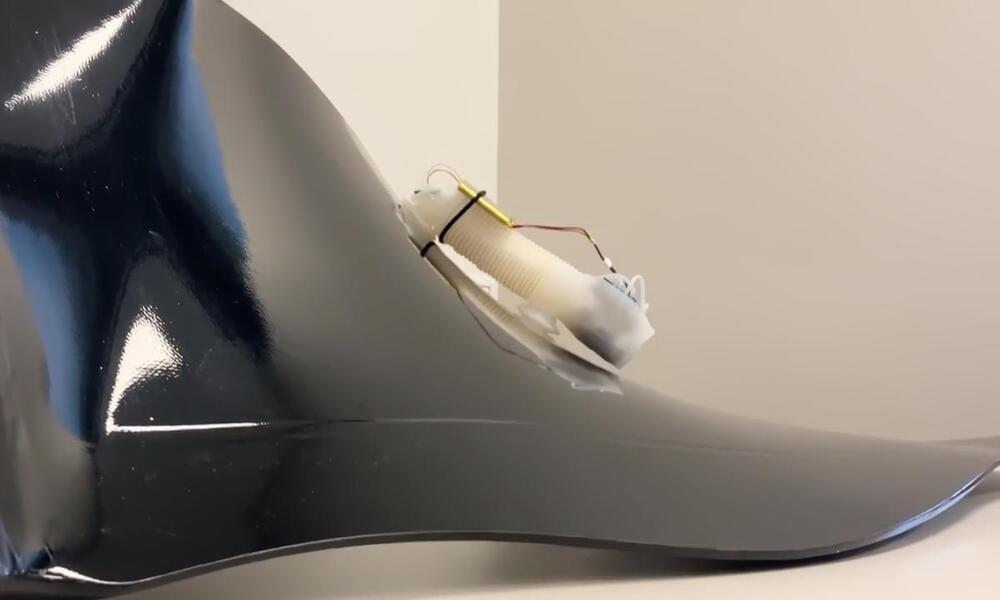

Researchers who created a soft robot that could navigate simple mazes without human or computer direction have now built on that work, creating a “brainless” soft robot that can navigate more complex and dynamic environments. The paper, “Physically Intelligent Autonomous Soft Robotic Maze Escaper,” was published Sept. 8 in the journal Science Advances.

“In our earlier work, we demonstrated that our soft robot was able to twist and turn its way through a very simple obstacle course,” says Jie Yin, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University. “However, it was unable to turn unless it encountered an obstacle. In practical terms this meant that the robot could sometimes get stuck, bouncing back and forth between parallel obstacles.

We’ve developed a new soft robot that is capable of turning on its own, allowing it to make its way through twisty mazes, even negotiating its way around moving obstacles. And it’s all done using physical intelligence, rather than being guided by a computer.