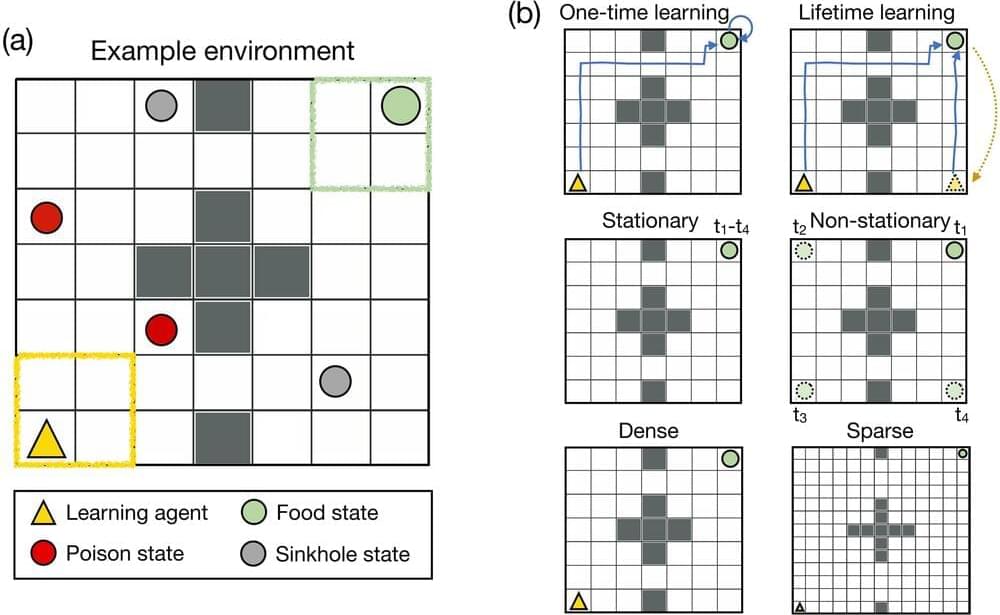

A trio of researchers, two with Princeton University, the other the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, has developed a reinforcement learning–based simulation that shows the human desire always to want more may have evolved as a way to speed up learning. In their paper posted in the open-access PLOS Computational Biology, Rachit Dubey, Thomas Griffiths and Peter Dayan describe the factors that went into their simulations.

Researchers studying human behavior have often been puzzled by people’s seemingly contradictory desires. Many people have an unceasing desire for more of certain things, even though they know that meeting those desires may not result in the desired outcome. Many people want more and more money, for example, with the idea that more money would make life easier, which should make them happier. But a host of studies has shown that making more money rarely makes people happier (with the exception of those starting from a very low income level). In this new effort, the researchers sought to better understand why people would have evolved this way. To that end, they built a simulation to mimic the way humans respond emotionally to stimuli, such as achieving goals. And to better understand why people might feel the way they do, they added checkpoints that could be used as a happiness barometer.

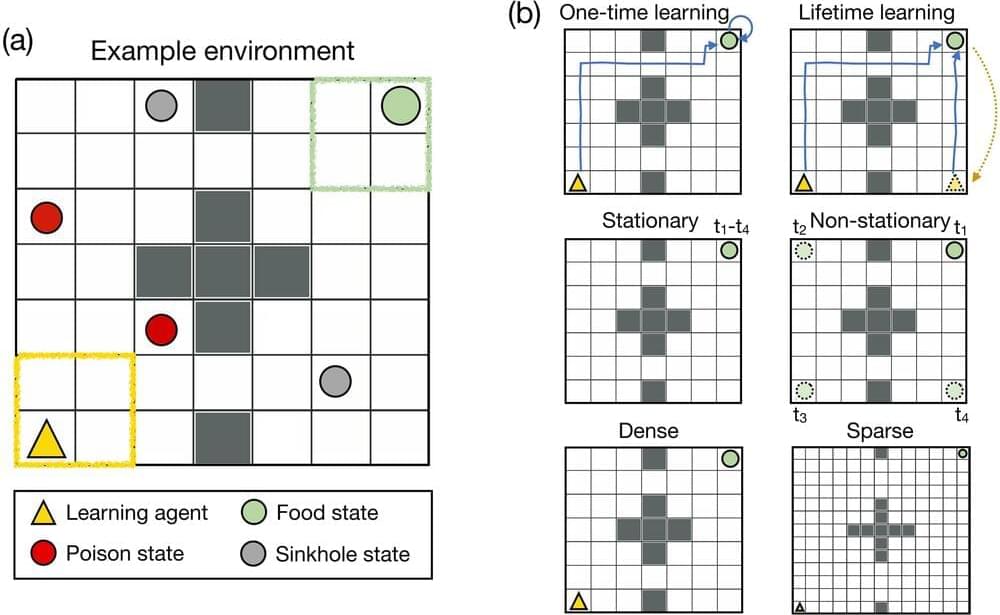

The simulation was based on reinforcement learning, in which people (or a machine) continue doing things that offer a positive reward and cease doing things that offer no reward or a negative reward. The researchers also added simulated emotional reactions to the known negative impacts of habituation and comparison, whereby people become less happy over time as they get used to something new and become less happy when seeing that someone else has more of something they want.