Thousands of people and pets are signed up to be preserved in chambers at liquid nitrogen temperatures in the hopes of being resuscitated one day.

Google’s conversation AI tool Bard can now help software developers with programming, including generating code, debugging and code explanation — a new set of skills that were added in response to user demand.

Coding has been one of the top requests Google has received from users, according to a Friday blog post by Google Research product lead Paige Bailey.

Google said Friday it is launching these software development capabilities in more than 20 programming languages including C++, Go, Java, JavaScript, Python and TypeScript. Users can export Python code to Google Colab. Bard can also help with writing functions for Google Sheets.

Figured reliefs found at the Casas del Turuñuelo site (Badajoz). / Samuel Sanchez (El País)

BADAJOZ, Spain — Archaeologists excavating the ancient Tartessian site of Casas del Turuñuelo have uncovered the first human representations of the ancient Tartessos people, shedding light on the Bronze Age civilization that mysteriously vanished around 2,500 years ago.

The historical and lost civilization of Tartessos flourished in southern Spain and has been previously linked to the myth of Atlantis.

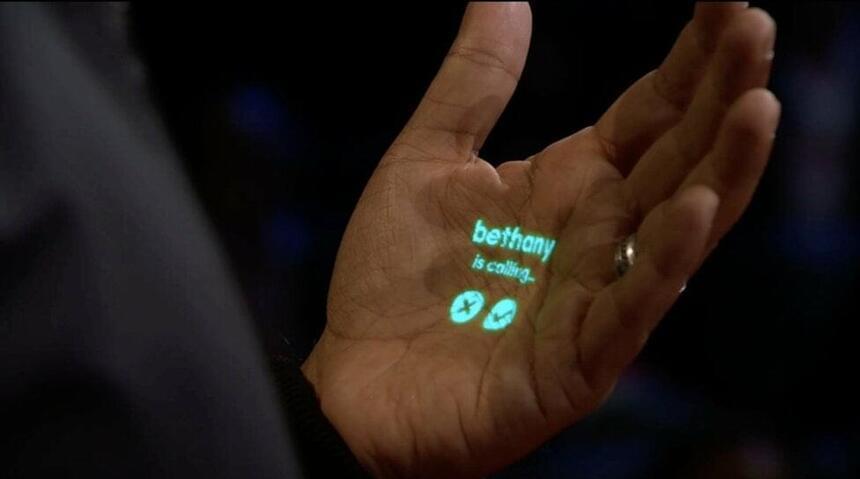

Mini GPT 4 has visual understanding abilities to carry out reasoning from pictures and complete numerous next gen AI tasks all before OpenAI releases their own visual modality. Nvidia unveils next gen text to video artificial intelligence model that can be customized.

Deep Learning AI Specialization: https://imp.i384100.net/GET-STARTED

AI Marketplace: https://taimine.com/

Try Mini GPT 4 here: https://minigpt-4.github.io/

AI news timestamps:

0:00 Mini GPT 4 AI

3:13 Model architecture.

5:06 Nvidia text to video.

#ai #future #tech

This group might appreciate this new show about fighting the AI overlord, lol:

Mrs. Davis is streaming April 20th on Peacock: https://pck.tv/3IMMtIP

Synopsis: “Mrs. Davis is the world’s most powerful Artificial Intelligence. Simone is the nun devoted to destroying Her. Who ya got?

#Peacock #MrsDavis #OfficialTrailer.

About Peacock: Stream current hits, blockbuster movies, bingeworthy TV shows, and exclusive Originals — plus news, live sports, WWE, and more. Peacock’s got your faves, including Parks & Rec, Yellowstone, Modern Family, and every episode of The Office. Peacock is currently available to stream within the United States.

Live from the Center for Future Mind and the Gruber Sandbox at Florida Atlantic University, Join us for an interactive Q&A with Yudkowsky about Al Safety! El…

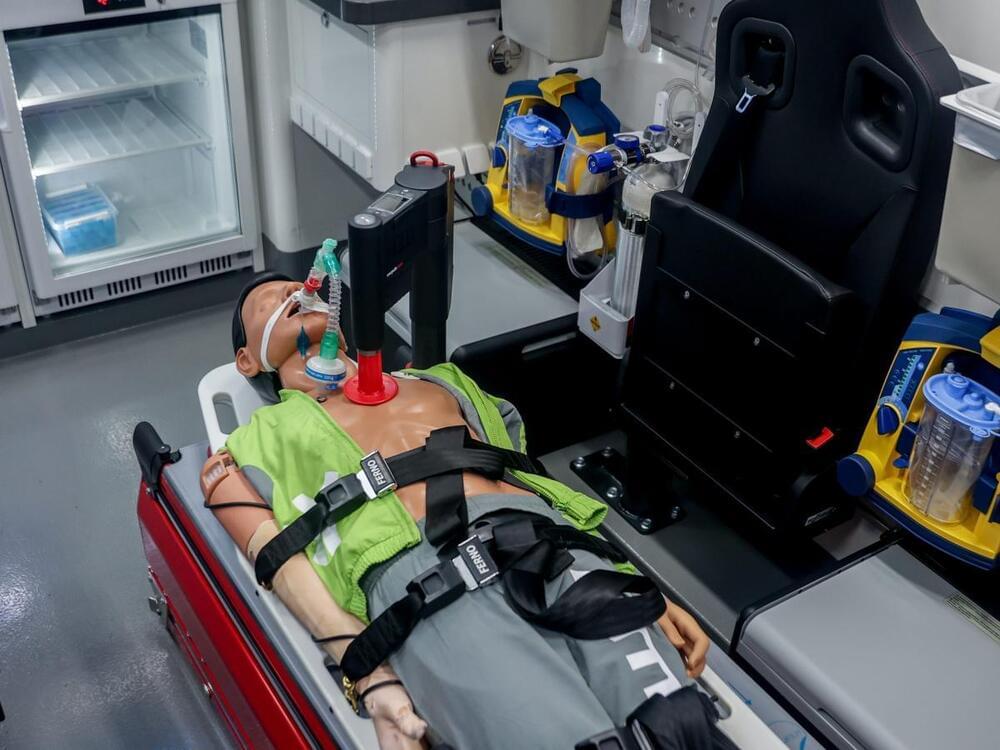

And it could fly to orbit, in only one launch, by the early 2030s.

European aerospace giant Airbus has just revealed a new concept space habitat called LOOP. The 26-foot-wide (8 meters) multi-purpose orbital module will feature three customizable decks, all of which will be connected by a tunnel overlooking a space greenhouse.

In a press statement, Airbus said its new space station design could accommodate up to eight crew members, and it could be deployed to orbit, in only one launch, by the early 2030s.

Airbus.

The 26-foot-wide (8 meters) multi-purpose orbital module will feature three customizable decks, all of which will be connected by a tunnel overlooking a space greenhouse.