Generative AI and other easy-to-use software tools can help employees with no coding background become adept programmers, or what the authors call citizen developers. By simply describing what they want in a prompt, citizen developers can collaborate with these tools to build entire applications—a process that until recently would have required advanced programming fluency.

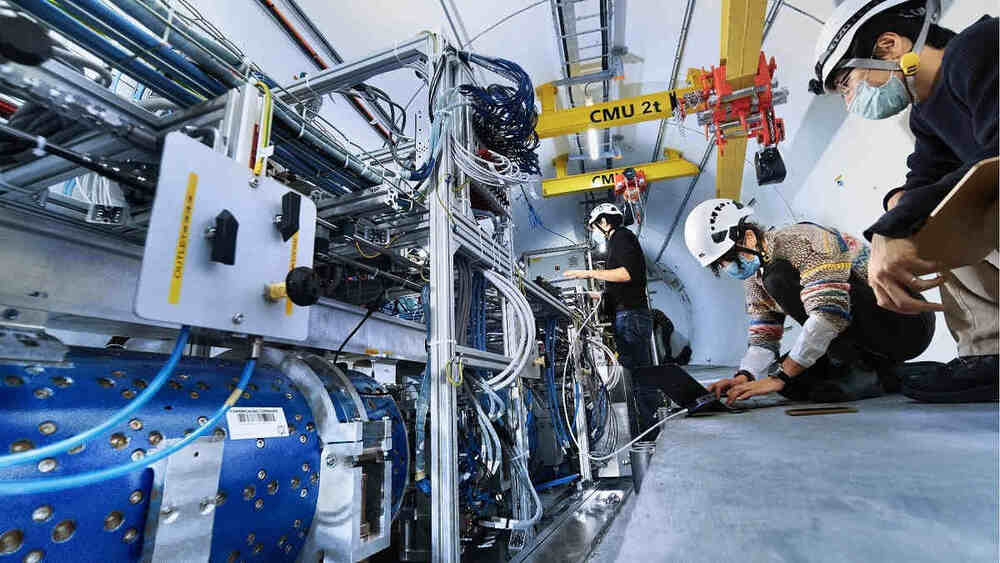

Information technology has historically involved builders (IT professionals) and users (all other employees), with users being relatively powerless operators of the technology. That way of working often means IT professionals struggle to meet demand in a timely fashion, and communication problems arise among technical experts, business leaders, and application users.

Citizen development raises a critical question about the ultimate fate of IT organizations. How will they facilitate and safeguard the process without placing too many obstacles in its path? To reject its benefits is impractical, but to manage it carelessly may be worse. In this article the authors share a road map for successfully introducing citizen development to your employees.