A new thermal transistor can control heat as precisely as an electrical transistor can control electricity.

By Rachel Nuwer

A new thermal transistor can control heat as precisely as an electrical transistor can control electricity.

By Rachel Nuwer

Scientists have fused brain-like tissue with electronics to make an ‘organoid neural network’ that can recognise voices and solve a complex mathematical problem. Their invention extends neuromorphic computing – the practice of modelling computers after the human brain – to a new level by directly including brain tissue in a computer.

The system was developed by a team of researchers from Indiana University, Bloomington; the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Centre, Cincinnati; and the University of Florida, Gainesville. Their findings were published on December 11.

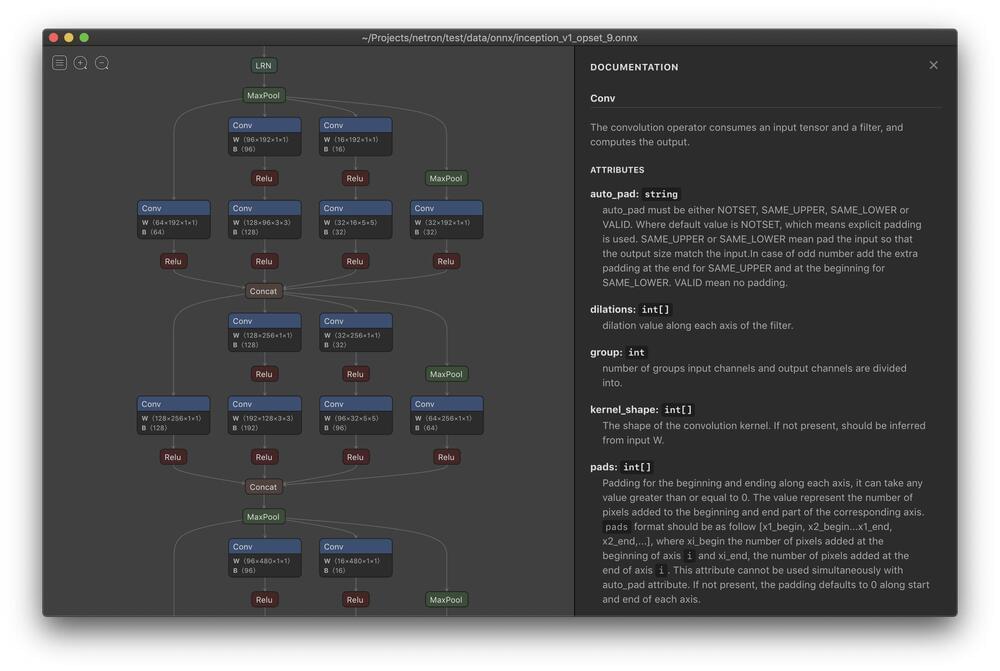

Exploring pre-trained models for research often poses a challenge in Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL). Visualizing the architecture of these models usually demands setting up the specific framework they were trained on, which can be quite laborious. Without this framework, comprehending the model’s structure becomes cumbersome for AI researchers.

Some solutions enable model visualization but involve setting up the entire framework for training the model. This process can be time-consuming and intricate, deterring quick access to model architectures.

One solution to simplify the visualization of ML/DL models is the open-source tool called Netron. This tool functions as a viewer specifically designed for neural networks, supporting frameworks like TensorFlow Lite, ONNX, Caffe, Keras, etc. Netron bypasses the need to set up individual frameworks by directly presenting the model architecture, making it accessible and convenient for researchers.

How the brain adjusts connections between #neurons during learning: this new insight may guide further research on learning in brain networks and may inspire faster and more robust learning #algorithms in #artificialintelligence.

Researchers from the MRC Brain Network Dynamics Unit and Oxford University’s Department of Computer Science have set out a new principle to explain how the brain adjusts connections between neurons during learning. This new insight may guide further research on learning in brain networks and may inspire faster and more robust learning algorithms in artificial intelligence.

The essence of learning is to pinpoint which components in the information-processing pipeline are responsible for an error in output. In artificial intelligence, this is achieved by backpropagation: adjusting a model’s parameters to reduce the error in the output. Many researchers believe that the brain employs a similar learning principle.

However, the biological brain is superior to current machine learning systems. For example, we can learn new information by just seeing it once, while artificial systems need to be trained hundreds of times with the same pieces of information to learn them. Furthermore, we can learn new information while maintaining the knowledge we already have, while learning new information in artificial neural networks often interferes with existing knowledge and degrades it rapidly.

In a new study published in Cancer Cell, YSM researchers at Yale Cancer Center find immunotherapy could benefit thousands of additional patients with colorectal and endometrial cancers who are not currently being offered it:

A new study shows thousands more patients diagnosed with colorectal and endometrial cancers could benefit from immunotherapy than are currently offered it. Researchers showed the importance of looking at DNA Mismatch Repair Deficiency (MMR-D) as a guiding marker for treatment decisions using immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). MMR-D is associated with an increased risk of developing several types of cancer and is the most common cause of hereditary endometrial cancer.

The study, which published in Cancer Cell on December 28, compared two lab testing methods to diagnose cancers— traditional immunohistochemistry (IHC) (a lab technique that uses antibodies to detect antigens in tissues) — and next-generation sequencing (NGS) — a new technology used for DNA sequencing that can detect specific patterns of mutations. The researchers discovered that NGS offers a more accurate assessment of MMR status.

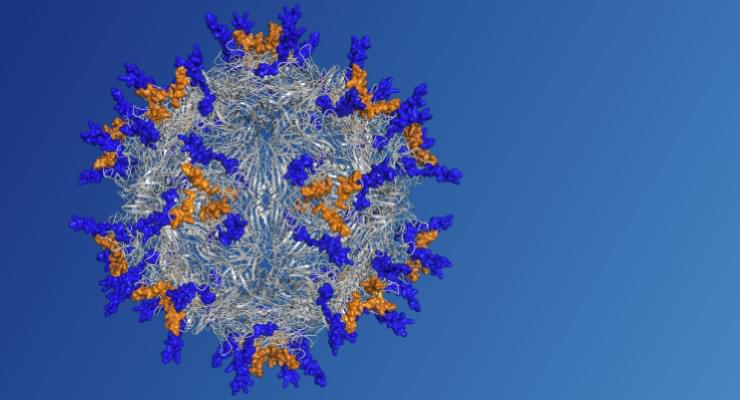

Voyager Therapeutics entered a strategic collaboration and capsid license agreement with Novartis to advance potential gene therapies for Huntington’s disease and spinal muscular atrophy, providing Novartis a target-exclusive license to access its TRACER capsids and other intellectual property.

Novartis obtains target-exclusive access to Voyager’s TRACER capsids related to Huntington’s disease and spinal muscular atrophy.