The judicious shaping of a tube of plasma by one laser enhances the properties of electron bunches accelerated by another.

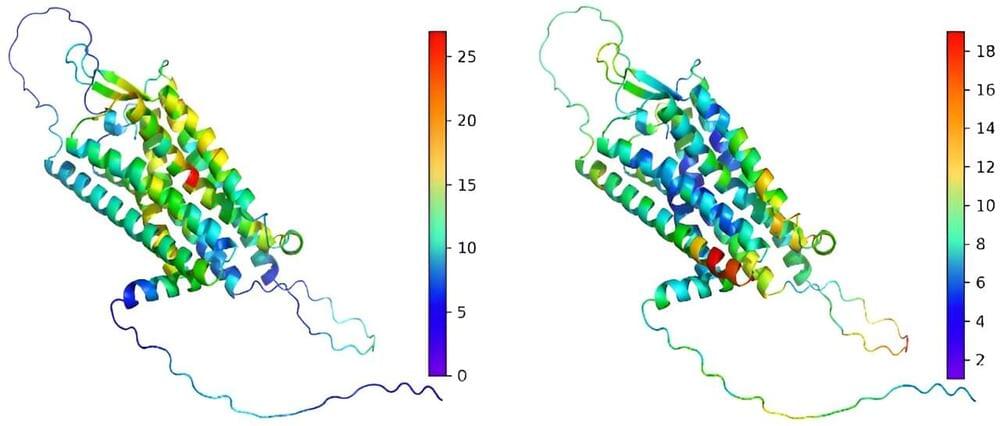

The idea was first proposed in 1979: use a laser to separate a plasma’s electrons from its ions, thereby creating an electric field that accelerates electrons to giga-electron-volt (GeV) energies over a few micrometers. Turning that idea into useful devices requires bestowing electrons with not just high energy but also with a tight spread in energy. Now a team led by Simon Hooker of Oxford University, UK, has demonstrated a plasma-preparation technique that yields 1.2 GeV electrons with an energy spread of 4.5% [1]. Although that performance falls short of conventional accelerators, further improvement is possible.

In general, the more intense the laser and the denser the plasma, the greater the electron acceleration. But if the laser–plasma interaction is pushed up into the nonlinear regime, the acceleration becomes unruly. Working at lower intensities and densities requires sustaining the acceleration for longer. It also requires that the electrons in the lowest-density part of the plasma are accelerated first. That way, the exiting electrons form a tight bunch.