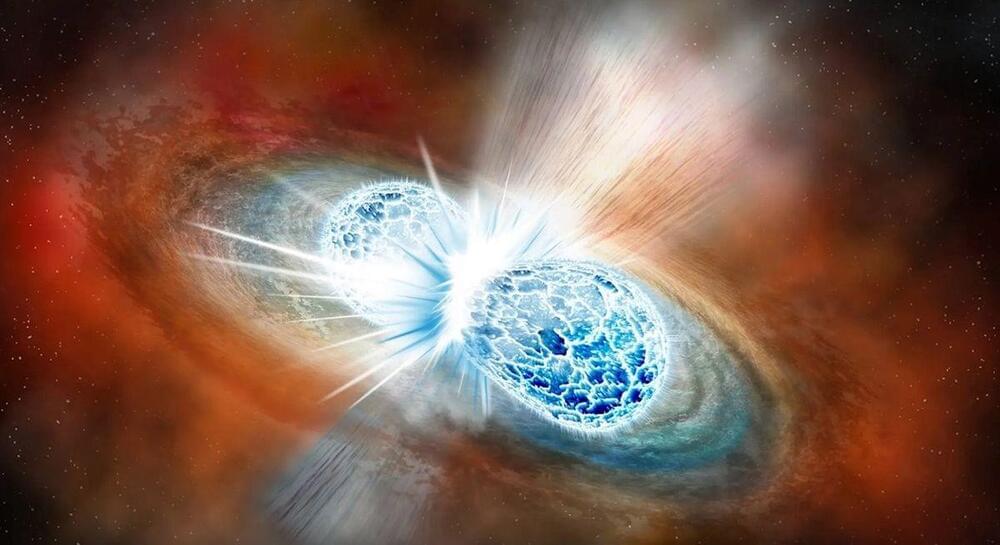

A kilonova is a bright blast of electromagnetic radiation that happens when two neutron stars or a neutron star and a stellar-mass black hole collide and merge.

When these collisions occur, a vast amount of material is ejected from the neutron stars, the ultradense cores of massive stars that have reached the ends of their lives. This matter is rich in neutral particles called neutrons, and in this violent sea of particles around a neutron star merger, the heaviest elements of the periodic table are forged. These include gold and platinum, radioactive materials such as uranium, and the iodine that flows through our blood. In fact, many pieces of jewelry owe their existence to a kilonova-triggering event.