Study finds measuring levels of a protein could be just as good at detecting disease as lumbar punctures.

It has long been thought that the ingredients for life came together slowly, bit by bit. Now there is evidence it all happened at once in a chemical big bang.

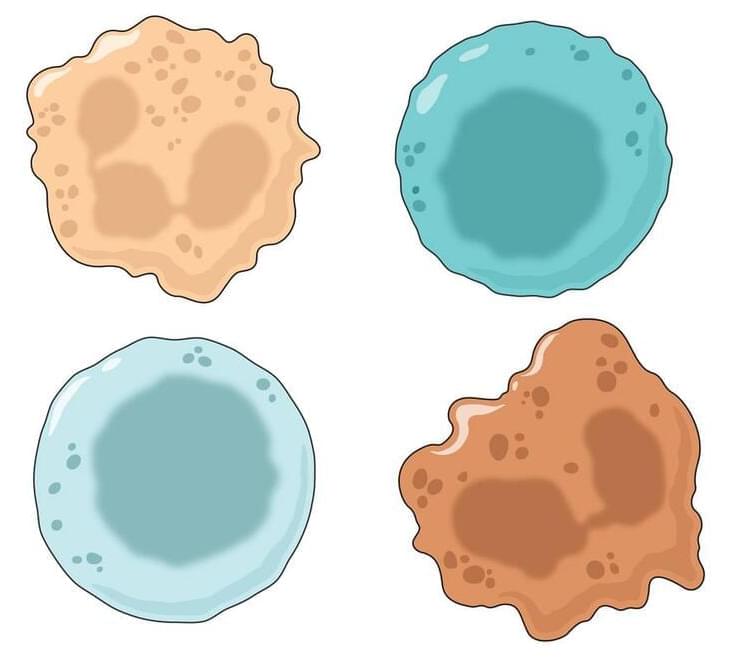

Three years old boy with reassuring development had presented to the Pediatric Neurology clinic with a referral due to a large head. Occipito-frontal circumference was more than 97th centile with an unremarkable neurological examination. MRI brain exhibited an acute on chronic large right frontoparietal subdural hematoma with prominent mass effect. Consequentially, the hematoma was evacuated by the neurosurgeon. Postoperative recovery stayed satisfactory. Hematology workup showed normal coagulation and clotting factors levels. Whole exome sequencing (WES) study revealed heterozygous variant c.5187G>A p.(Trp1729• in gene FBN1 — pathogenic for Marfan syndrome. However, this variant has not yet been reported in association with cerebral arteritis/intracerebral bleed. On follow-up, the child remained asymptomatic clinically with static head size.

By Chuck Brooks

Computing paradigms as we know them will exponentially change when artificial intelligence is combined with classical, biological, chemical, and quantum computing. Artificial intelligence might guide and enhance quantum computing, run in a 5G or 6G environment, facilitate the Internet of Things, and stimulate materials science, biotech, genomics, and the metaverse.

Computers that can execute more than a quadrillion calculations per second should be available within the next ten years. We will also rely on clever computing software solutions to automate knowledge labor. Artificial intelligence technologies that improve cognitive performance across all envisioned industry verticals will support our future computing.

Advanced computing has a fascinating and mind-blowing future. It will include computers that can communicate via lightwave transmission, function as a human-machine interface, and self-assemble and teach themselves thanks to artificial intelligence. One day, computers might have sentience.

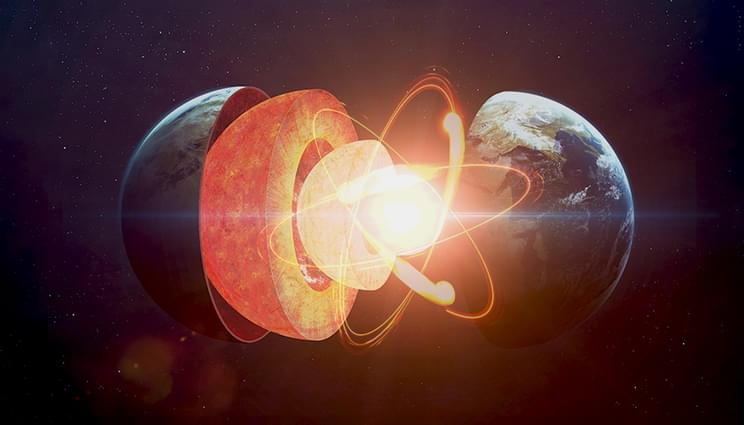

Iron is one of the world’s most abundant elements and a primary component of the Earth’s core. Understanding the behavior of iron under extreme conditions, such as ultra-high pressures and temperatures, has implications for the science of geology and the Earth’s evolution.

In a study conducted by a team led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. researchers combined lasers and X-ray diffraction methods to examine how different crystal structures of iron are related to each other and what happens when it melts at ultrahigh pressures and temperatures. The paper was published in the journal Physical Review B.

Using the Dynamic Compression Sector beamline at Argonne National Laboratory, researchers applied nanosecond laser shock compression to iron at pressures up to 275 gigapascals (GPa) — more than 2 million times atmospheric pressure — and used in situ picosecond X-ray diffraction to study the structure of the iron under these extreme conditions. Authors said the ability to gather this novel data on iron provides insights into materials science and the internal dynamics of Earth and other terrestrial exoplanets.

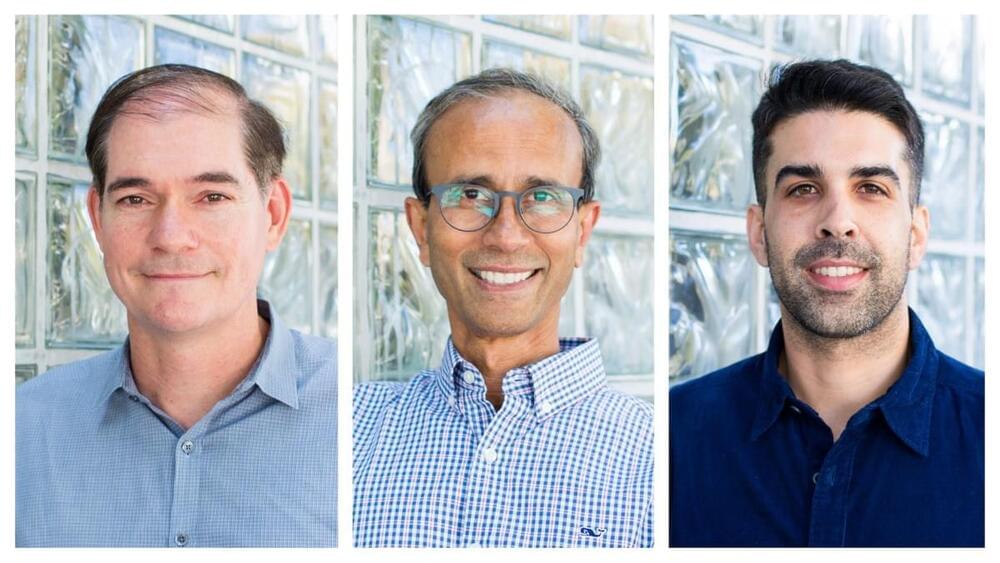

Thomvest Ventures is popping into 2024 with a new $250 million fund and the promotion of Umesh Padval and Nima Wedlake to the role of managing directors.

The Bay Area venture capital firm was started about 25 years ago by Peter Thomson, whose family is the majority owners of Thomson Reuters.

“Peter has always had a very strong interest in technology and what technology would do in terms of shaping society and the future,” Don Butler, Thomvest Ventures’ managing director, told TechCrunch. He met Thomson in 1999 and joined the firm in 2000.

Will AI automate human jobs, and — if so — which jobs and when?

That’s the trio of questions a new research study from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), out this morning, tries to answer.

There’s been many attempts to extrapolate out and project how the AI technologies of today, like large language models, might impact people’s’ livelihoods — and whole economies — in the future.