Professor Mallet spent his life researching time travel in order to be able to go back and visit his dead father — now he claims he invented a time machine.

Previously Fahy has reported as much as a 15 year epigenetic clock reset. Again though, this won’t get you beyond your maximum natural limit, but younger and healthier now leads to the next bridge.

Dr Greg Fahy talks about the thymus magic. What are the out of expectation benefits of reprogramming our thymus(Not TRIIM or TRIIM-X) in this short clip.

Gregory M. Fahy is a cryobiologist and biogerontologist, and is also Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer at Twenty-First Century Medicine, Inc. Fahy is the world’s foremost expert in organ cryopreservation by vitrification. Fahy introduced the modern successful approach to vitrification for cryopreservation in cryobiology and he is widely credited, along with William F. Rall, for introducing vitrification into the field of reproductive biology.

Fahy is also a well-known biogerontologist and is the originator and Editor-in-Chief of The Future of Aging: Pathways to Human Life Extension, a multi-authored book on the future of biogerontology. He currently serves on the editorial boards of Rejuvenation Research and the Open Geriatric Medicine Journal and served for 16 years as a Director of the American Aging Association and for 6 years as the editor of AGE News, the organization’s newsletter.

=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*=*

The world has been learning an awful lot about artificial intelligence lately, thanks to the arrival of eerily human-like chatbots.

Less noticed, but just as important: Researchers are learning a great deal about us – with the help of AI.

AI is helping scientists decode how neurons in our brains communicate, and explore the nature of cognition. This new research could one day lead to humans connecting with computers merely by thinking–as opposed to typing or voice commands. But there is a long way to go before such visions become reality.

Recent public interest in tools like ChatGPT has raised an old question in the artificial intelligence community: is artificial general intelligence (in this case, AI that performs at human level) achievable? An online preprint this week has added to the hype, suggesting the latest advanced large language model, GPT-4, is at the early stages of artificial general intelligence (AGI) as it’s exhibiting “sparks of intelligence”.

Dr Ajaz Ali predicts that our loved ones who pass away will continue to exist in a digital form thanks to Artificial Intelligence ‘capturing’ their looks and personality People will be able to ‘live on’ after death thanks to powerful AI technology, a computer expert has claimed.

Join us on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/MichaelLustgartenPhD

Discount Links:

NAD+ Quantification: https://www.jinfiniti.com/intracellular-nad-test/

Use Code: ConquerAging At Checkout.

Green Tea: https://www.ochaandco.com/?ref=conqueraging.

Oral Microbiome: https://www.bristlehealth.com/?ref=michaellustgarten.

Epigenetic Testing: https://bit.ly/3Rken0n.

Use Code: CONQUERAGING!

At-Home Blood Testing: https://getquantify.io/mlustgarten.

The pursuit of a cure for Alzheimer’s disease is becoming an increasingly competitive and contentious quest with recent years witnessing several important controversies.

In July 2022, Science magazine reported that a key 2006 research paper, published in the prestigious journal Nature, which identified a subtype of brain protein called beta-amyloid as the cause of Alzheimer’s, may have been based on fabricated data.

One year earlier, in June 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration had approved aducanumab, an antibody-targeting beta-amyloid, as a treatment for Alzheimer’s, even though the data supporting its use were incomplete and contradictory.

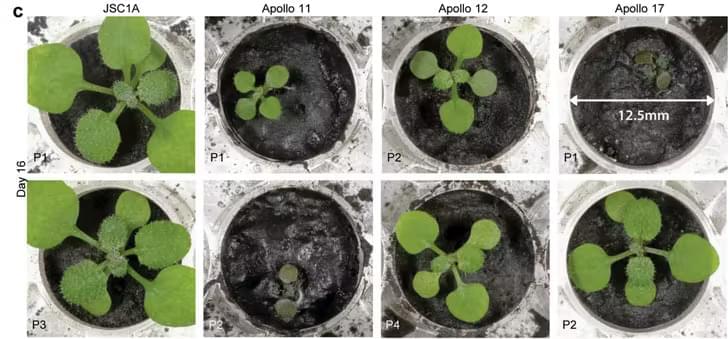

Plants could be grown in Moon soil, a new study shows. The findings on plant stress responses have the potential to help develop drought-resistant crops.

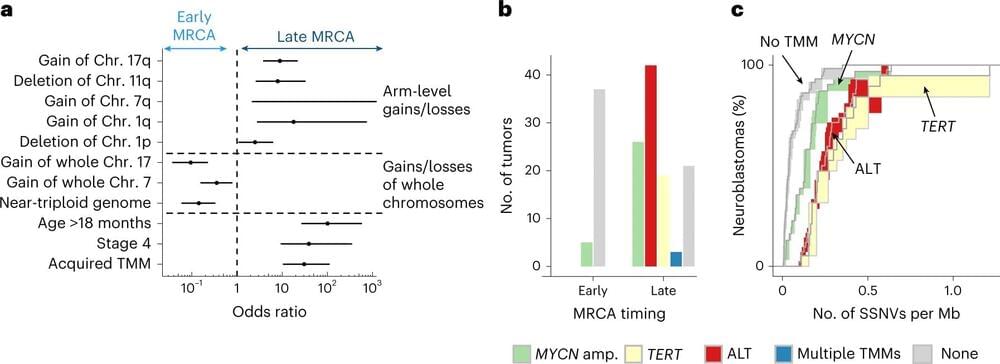

A research team led by the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, Germany, has discovered that the genetic sequence of a tumor can be read like a molecular clock, traced back to its most recent common ancestor cell. Extracting the duration of tumor evolution can give an accurate predictor of neuroblastoma outcomes.

In a paper published in Nature Genetics titled “Neuroblastoma arises in early fetal development and its evolutionary duration predicts outcome,” the team details the steps they took in identifying a genomic clock tested against a whole genome sequenced population combined with analysis and mathematical modeling, to identify evolution markers, traceability and a likely origin point of infant neuroblastomas.

Cancer cells start out life as heroic healthy tissues, with the sort of all for one, one for all, throw yourself on a grenade to save your mates–type attitude that is taking place throughout the body every day. At some point, something goes wrong, and a good cell goes bad.

The use of time-lapse monitoring in IVF does not result in more pregnancies or shorten the time it takes to get pregnant. This new method, which promises to “identify the most viable embryos,” is more expensive than the classic approach. Research from Amsterdam UMC, published today in The Lancet, shows that time-lapse monitoring does not improve clinical results.

Patients undergoing an IVF treatment often have several usable embryos. The laboratory then makes a choice as to which embryo will be transferred into the uterus. Crucial to this decision is the cell division pattern in the first three to five days of embryo development. In order to observe this, embryos must be removed from the incubator daily to be checked under a microscope. In time-lapse incubators, however, built-in cameras record the development of each embryo. This way embryos no longer need to be removed from the stable environment of the incubator and a computer algorithm calculates which embryo has shown the most optimal growth pattern.

More and more IVF centers, across the world, use time-lapse monitoring for the evaluation and selection of embryos. Prospective parents are often promised that time-lapse monitoring will increase their chance of becoming pregnant. Despite frequent use of this relatively expensive method, there are hardly any large clinical studies evaluating the added value of time-lapse monitoring for IVF treatments.