For more videos and information from Philip Clayton click here http://bit.ly/1CCgAsDFor more videos on how emergence can explain reality click here http://bit.ly/1CCgAsDFor

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

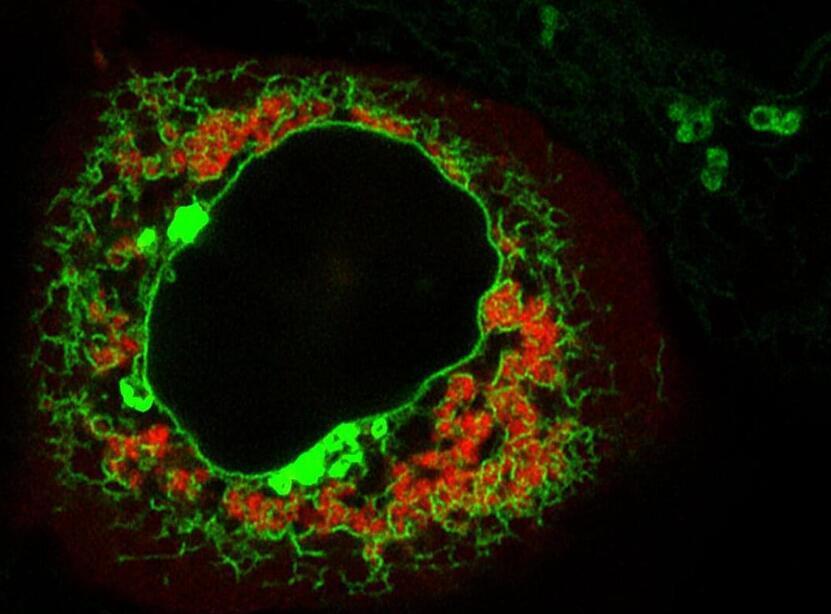

Location, location, location: Research reveals the hidden power of intracellular neighborhoods

New findings published in Molecular Cell provide details about the hidden organization of the cytoplasm—the soup of liquid, organelles, proteins, and other molecules inside a cell. The research shows it makes a big difference where in that cellular broth, messenger RNA (mRNA) gets translated into proteins.

“You know the old real estate saying, ‘location, location, location.’ It turns out it applies to how proteins get made inside of cells, too,” says Dr. Mayr, a molecular and cell biologist at the Sloan Kettering Institute, a hub for basic and translational research within MSK. “If it’s translated over here, you get twice as much protein as if it’s translated over there.”

This first-of-its-kind study highlights the degree to which the cytoplasm is “beautifully organized” rather than being just a big jumble of stuff, she says.

Finally!! SpaceX Conducts New Starship Hardware Test! — SpaceX Weekly #94

This week at Starbase Booster 10 joins Ship 28 at the launch site to begin its testing on the orbital launch mount, Ship 28 performs a static fire test, and SpaceX shows off its holiday spirit, while over at Cape Canaveral, Starlink launch and recovery operations continue as several tanks and a prefabricated tower section are shipped out to Brownsville.\

\

Thanks for watching this week’s LabPadre Update!\

\

If you would like to get involved with our community or learn more about Rockets and Space, please feel free to join our LabPadre Discord server at / discord \

\

X: https://x.com/LabPadre\

Instagram: / labpadre \

\

Browse our online store!\

http://shop.labpadre.com/\

\

Support us on Patreon and get special perks!\

/ labpadre \

\

Other ways you can support:\

PayPal — https://paypal.me/labpadre\

Cashapp — $LabPadre\

Venmo — @LabPadre\

BitCoin Wallet: bc1q7w0932yn2xk9ympkm2uzn28pnm90qzmplr4yew\

\

Patreon Elite/Royalty Crew: Tim Dodd, Eric Beavers, Marcus House, Matt Lowne, Zack Golden, Colin Smith, Steve Roberts, Azatht, Stumpy, Peter Lehrack, Eagle Eye Chuck, Gort, Robert Castle, Seth Count, Unreal Patch, Wil Schweitzer\

\

Special thanks to:\

Audio/Video Editors: Lucid, timmy\

Videography: LabPadre, Kevin Randolph, Spaceflight Now\

Photography: Kevin Randolph\

Clip Capture Bot: Arc\

Clip Reporting: Anomalia, DaOPCreeper, Jon Tait, Kalim, Vix, WLAnimal\

Script Editors: 61Naps, Jon Tait, Lucid\

Script Writers: WLAnimal\

\

Images may not be used without written consent from LabPadre Media or their rightful owner.

The Genetic Revolution: The Manipulation of Human DNA | Documentary

The Genetic Revolution is a compelling science documentary that invites viewers into the groundbreaking world of DNA manipulation and genetic engineering. This intriguing documentary showcases the innovative science behind genetic modifications and chronicles a diverse team of scientists from around the world as they utilize advanced DNA editing technologies like CRISPR in ways previously deemed unthinkable.\

With its exploration into the rapidly evolving science of DNA editing, \.

Gravitas: China’s golden veil | Gravitas Shorts

Chinese researchers have designed a new camouflage device that can make fighter jets appear like civilian planes on radars. Will this change the face of wars?\

\

#china #fighterjet #wion\

\

About Channel: \

\

WION The World is One News examines global issues with in-depth analysis. We provide much more than the news of the day. Our aim is to empower people to explore their world. With our Global headquarters in New Delhi, we bring you news on the hour, by the hour. We deliver information that is not biased. We are journalists who are neutral to the core and non-partisan when it comes to world politics. People are tired of biased reportage and we stand for a globalized united world. So for us, the World is truly One.\

\

Please keep discussions on this channel clean and respectful and refrain from using racist or sexist slurs and personal insults.\

\

Check out our website: http://www.wionews.com\

Join our WhatsApp Channel: https://bit.ly/455YOQ0\

Connect with us on our social media handles:\

Facebook: / wionews \

Twitter: / wionews \

\

Follow us on Google News for the latest updates\

\

Zee News:- https://bit.ly/2Ac5G60\

Zee Business:- https://bit.ly/36vI2xa\

DNA India:- https://bit.ly/2ZDuLRY\

WION: https://bit.ly/3gnDb5J\

Zee News Apps: https://bit.ly/ZeeNewsApps

Working Memory 2.0

MIT brain and cognitive sciences webinar.

Meet ELLiQ, an AI-enabled chatty companion robot for the elderly

Leveraging advancements in Genrative AI, the robot enables more immersive and continuous conversations, deepening the user-device connection.

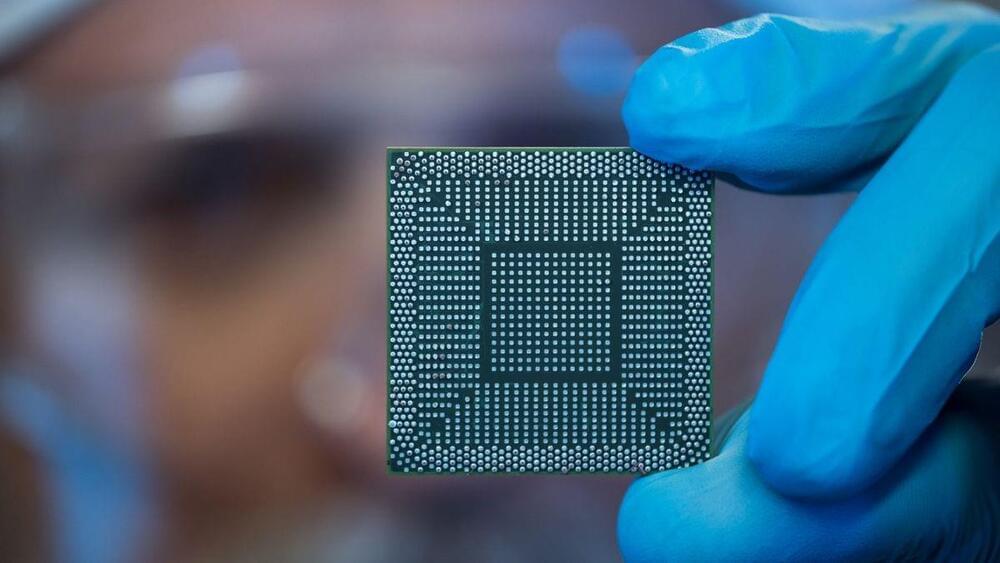

Wireless charger that sits under your skin could power medical devices before dissolving into your body

The researchers embedded this prototype in a biodegradable, chip-like implant that combined energy harvesting and energy storage. When the prototype was attached to a medical implant, power passed through the circuit directly to the device and into the capacitor to ensure a constant power supply.

In rats, the wireless implant worked for up to 10 days and dissolved completely within two months — proving its biodegradability. But it could potentially last longer if the team thickened the protective polymer and wax layers encasing the system, Lan said.

The researchers also tested the wireless charger as a drug-delivery system and delivered anti-inflammatory medicine to rats with a fever. After 12 hours, the rats that had no implants had much higher body temperatures than those with the chips, suggesting the device was successfully delivering the medicine.

Aging is just a disease! | Aubrey de Grey

Those who will live 1,000 years have already been born! They will not only live long, but will be healthy and active throughout life! This will already be possible in the transition phase of building the Creative Society!

We will talk about it in a live conversation with British biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey.

In this new episode of Health Navigator, you will find out the answers to these questions:

❓️ How will the future of people change if life expectancy is 1,000 years?

❓️ How can we move from traditional healthcare, which only treats the symptoms of disease, to preventive healthcare?

❓️ Why has Aubrey de Grey chosen preventative healthcare as his area of expertise?

❓️ Why is the Creative Society the type of human interaction that Aubrey de Grey would like to live and work in?