Metallenes are atomically thin metals whose unique properties make them extremely promising for nanoscale applications. However, their extreme thinness makes them also flimsy.

Integrated circuits are the brains behind modern electronic devices like computers or smart phones. Traditionally, these circuits—also known as chips—rely on electricity to process data. In recent years, scientists have turned their attention to photonic chips, which perform similar tasks using light instead of electricity to improve speed and energy efficiency.

When a gas is highly energized, its electrons get torn from the parent atoms, resulting in a plasma—the oft-forgotten fourth state of matter (along with solid, liquid, and gas). When we think of plasmas, we normally think of extremely hot phenomena such as the sun, lightning, or maybe arc welding, but there are situations in which icy cold particles are associated with plasmas. Images of distant molecular clouds from the James Webb Space Telescope feature such hot–cold interactions, with frozen dust illuminated by pockets of shocked gas and newborn stars.

Now a team of Caltech researchers has managed to recreate such an icy plasma system in the lab. They created a plasma in which electrons and positively charged ions exist between ultracold electrodes within a mostly neutral gas environment, injected water vapor, and then watched as tiny ice grains spontaneously formed.

They studied the behavior of the grains using a camera with a long-distance microscope lens. The team was surprised to find that extremely “fluffy” grains developed under these conditions and grew into fractal shapes—branching, irregular structures that are self-similar at various scales. And that structure leads to some unexpected physics.

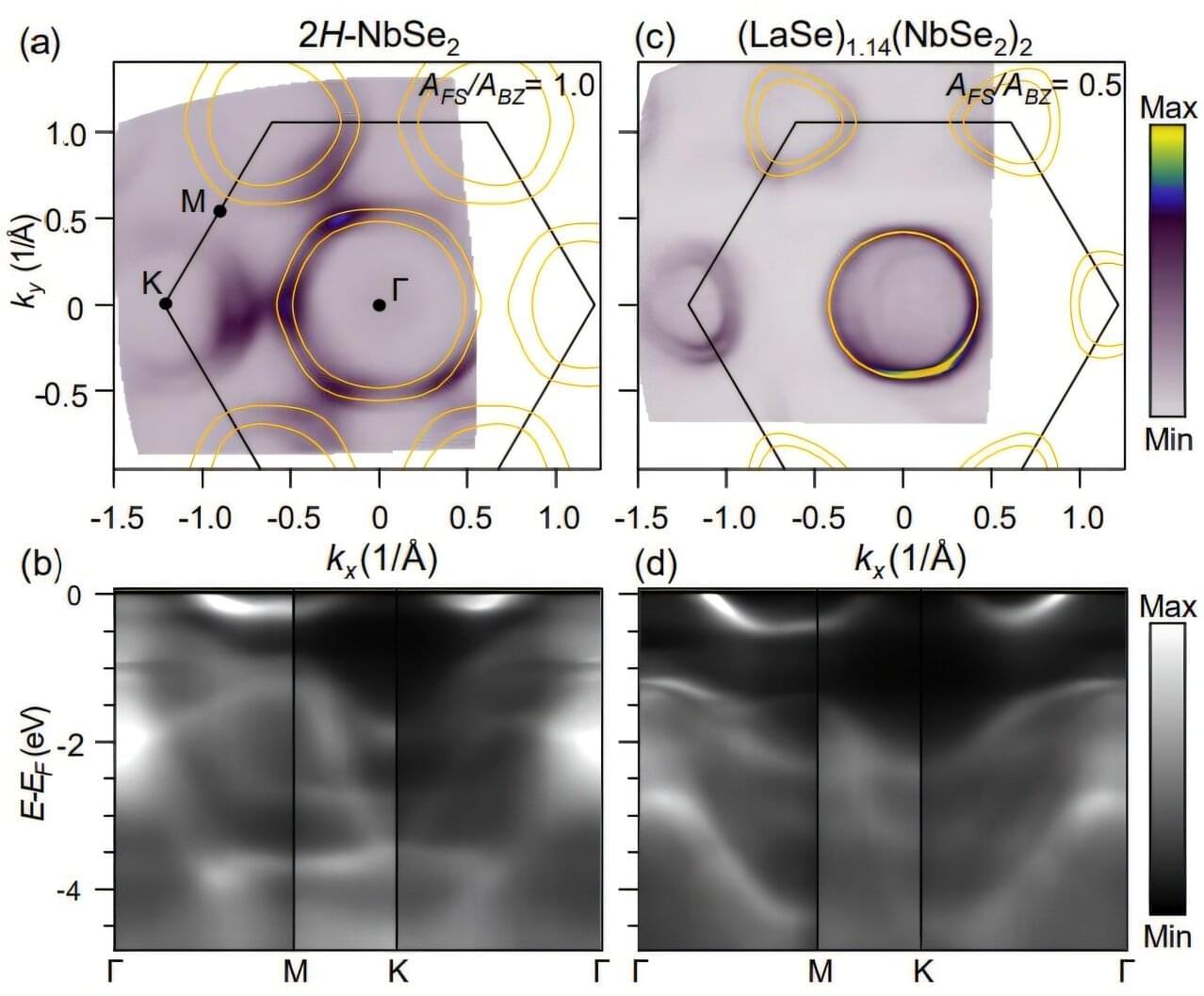

Electrons can be elusive, but Cornell researchers using a new computational method can now account for where they go—or don’t go—in certain layered materials.

Physics and engineering researchers have confirmed that in certain quantum materials, known as “misfits” because their crystal structures don’t align perfectly—picture LEGOs where one layer has a square grid and the other a hexagonal grid—electrons mostly stay in their home layers.

This discovery, important for designing materials with quantum properties including superconductivity, overturns a long-standing assumption. For years, scientists believed that large shifts in energy bands in certain misfit materials meant electrons were physically moving from one layer to the other. But the Cornell researchers have found that chemical bonding between the mismatched layers causes electrons to rearrange in a way that increases the number of high-energy electrons, while few electrons move from one layer to the other.

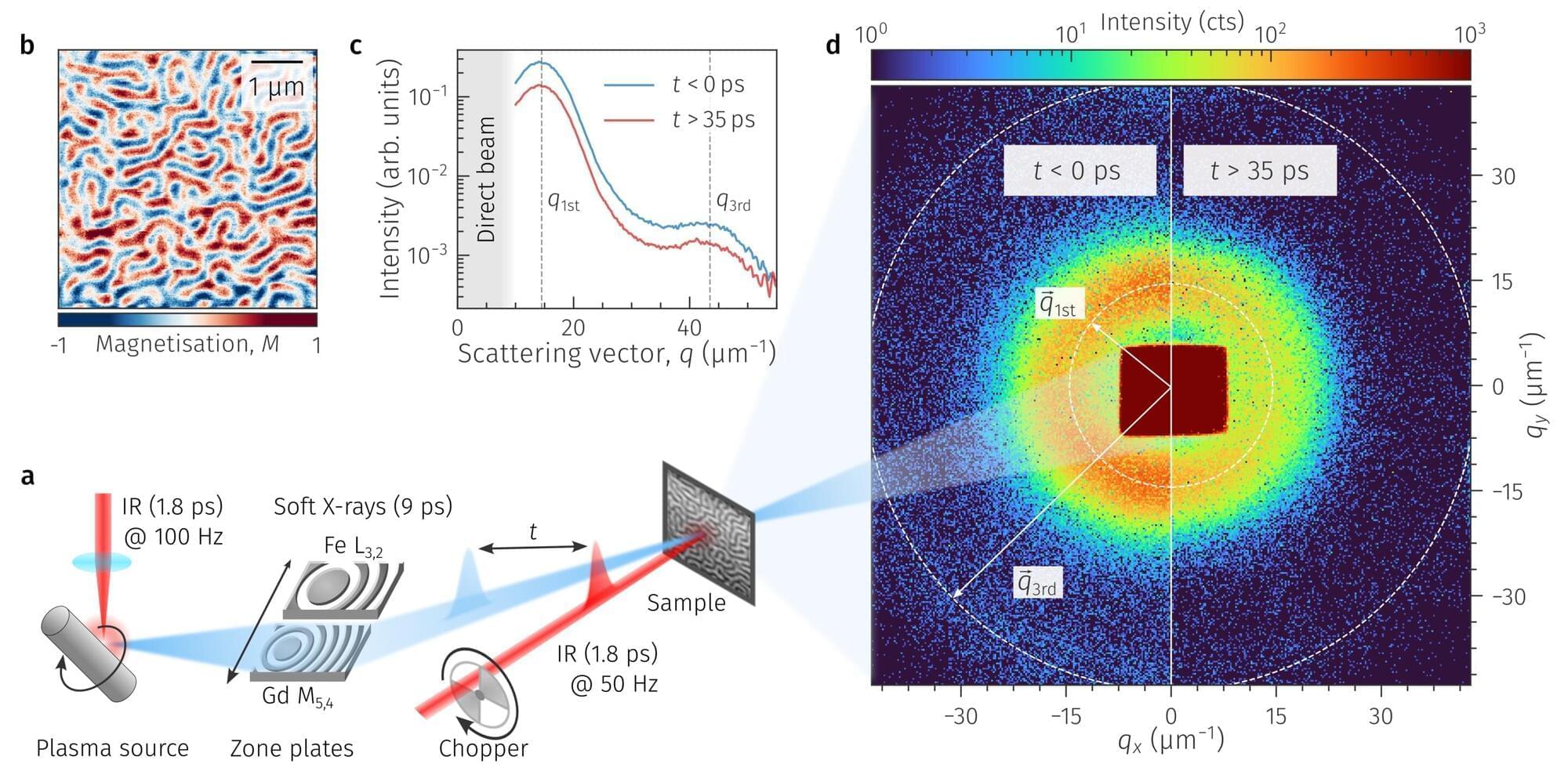

Scientists at the Max Born Institute have developed a new soft X-ray instrument that can reveal dynamics of magnetic domains on nanometer length and picosecond time scales. By bringing capabilities once exclusive to X-ray free-electron lasers into the laboratory, the work paves the way for routine investigations of ultrafast processes of emergent textures in magnetic materials and beyond.

A dropped fridge magnet offers a simple glimpse into a complex physical phenomenon: although it appears undamaged on the outside, its holding force can weaken because its internal magnetic structure has reorganized into countless tiny regions with opposing magnetization, so-called magnetic domains.

These nanoscale textures are central to modern magnetism research, but observing them at very short time scales has long required access to large-scale X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) facilities.