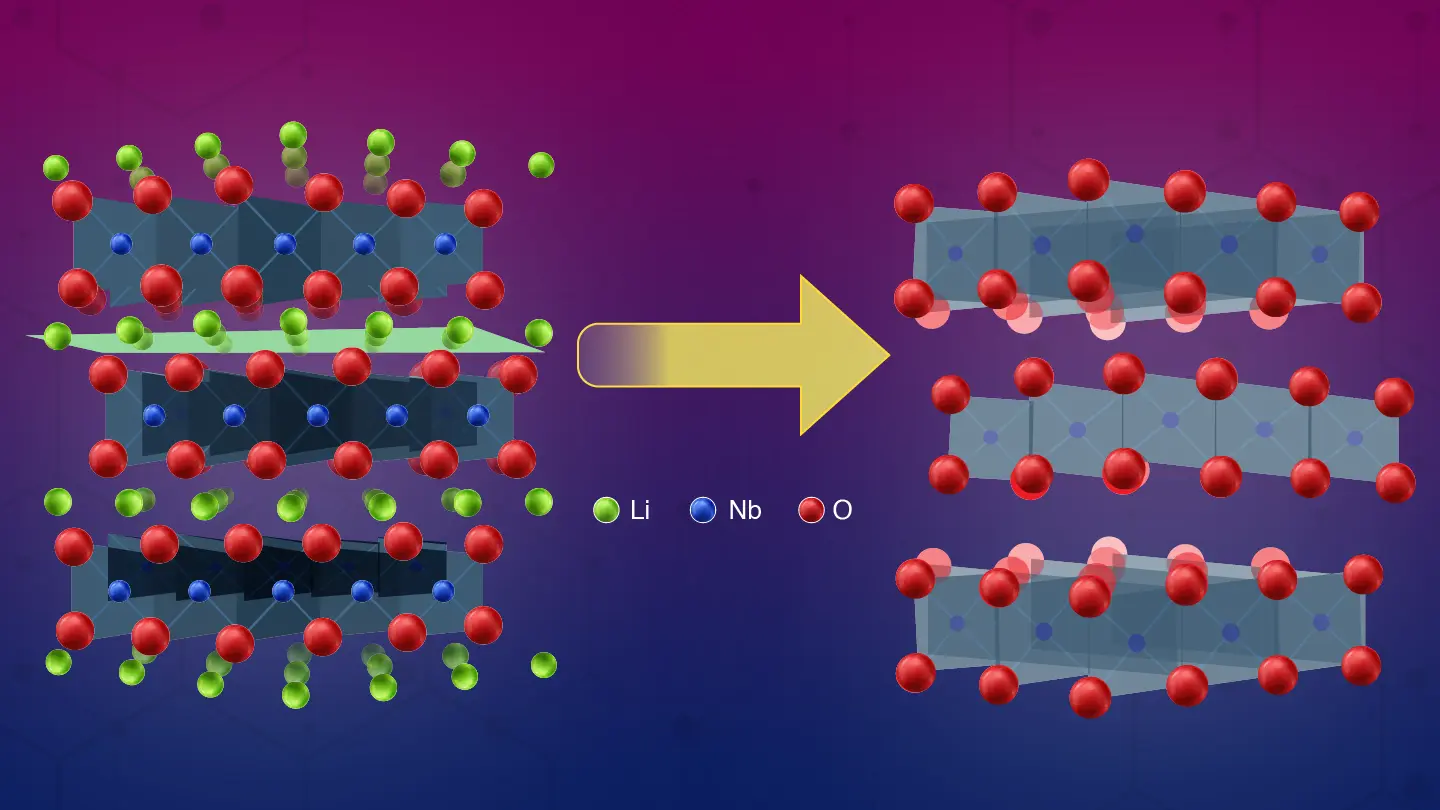

Scientists led by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) investigators have made a significant advance in developing alternative materials for the high-speed memory chips that let computers access information quickly and that bypass the limitations of existing materials.

They have discovered a way that allows them to make sense of previously hard-to-read data stored in these alternative materials, known as antiferromagnets.

Researchers consider antiferromagnets to be attractive materials for making computer memory chips because they are potentially more energy efficient than traditional ones made of silicon. Memory chips made of antiferromagnets are not subject to the size and speed constraints nor corruption issues that are inherent to chips made with certain magnetic materials.