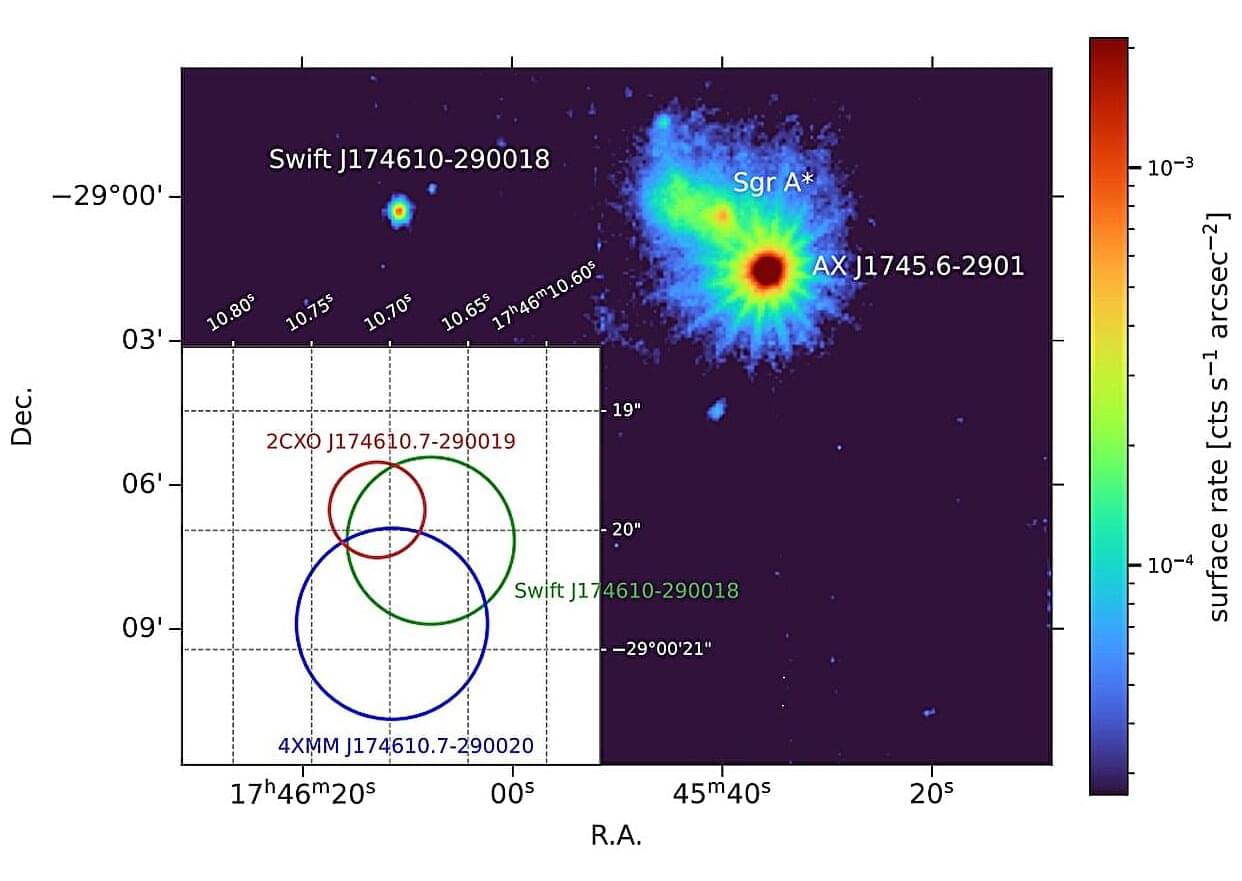

Using various space telescopes, an international team of astronomers have observed a newly detected very faint X-ray transient designated 4XMM J174610.7–290020. Results of the observational campaign, published October 2 on the arXiv pre-print server, yield new insights into the nature of this transient.

Very faint X-ray transients (VFXTs) are X-ray binary systems experiencing occasional outbursts with peak X-ray luminosities lower than an undecillion erg/s, therefore fainter than typical X-ray binaries. To date, only a few tens of VFXTs have been detected in the Milky Way, and about a dozen in the center of our galaxy.

Due to their typical low fluxes, the number of VFXTs that have been investigated in detail is still very small. Therefore, finding new VFXTs and studying them is essential to get a comprehensive view of the population of these transients.