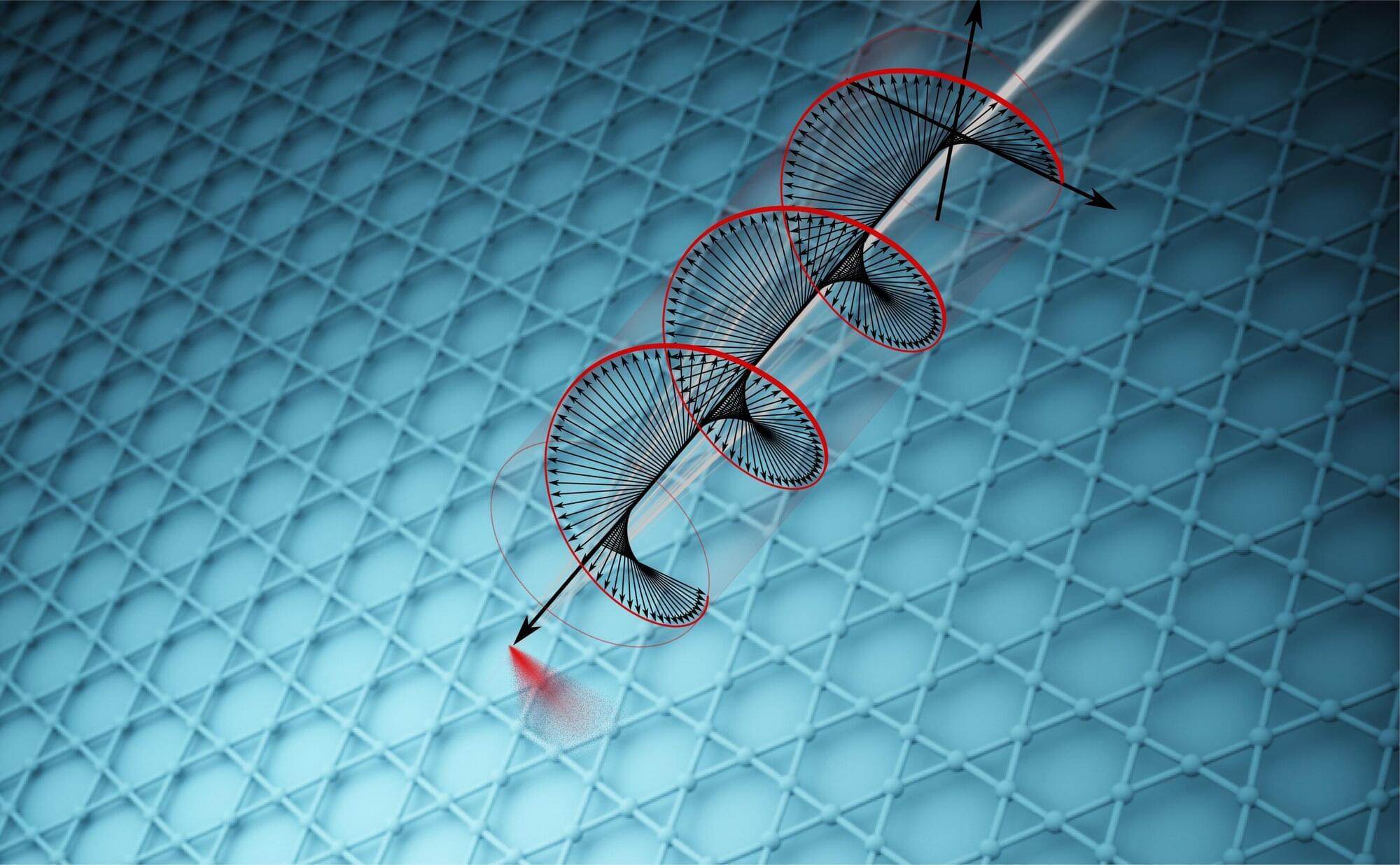

Chirality—the property of an object that is distinct from its mirror image—has long captivated scientists across biology, chemistry, and physics. The phenomenon is sometimes called “handedness,” because it refers to an object possessing a distinct left- or right-handed form. It is a universal quality that is found across various scales of nature, from molecules and amino acids to the famed double-helix of DNA and the spiraling patterns of snail shells.

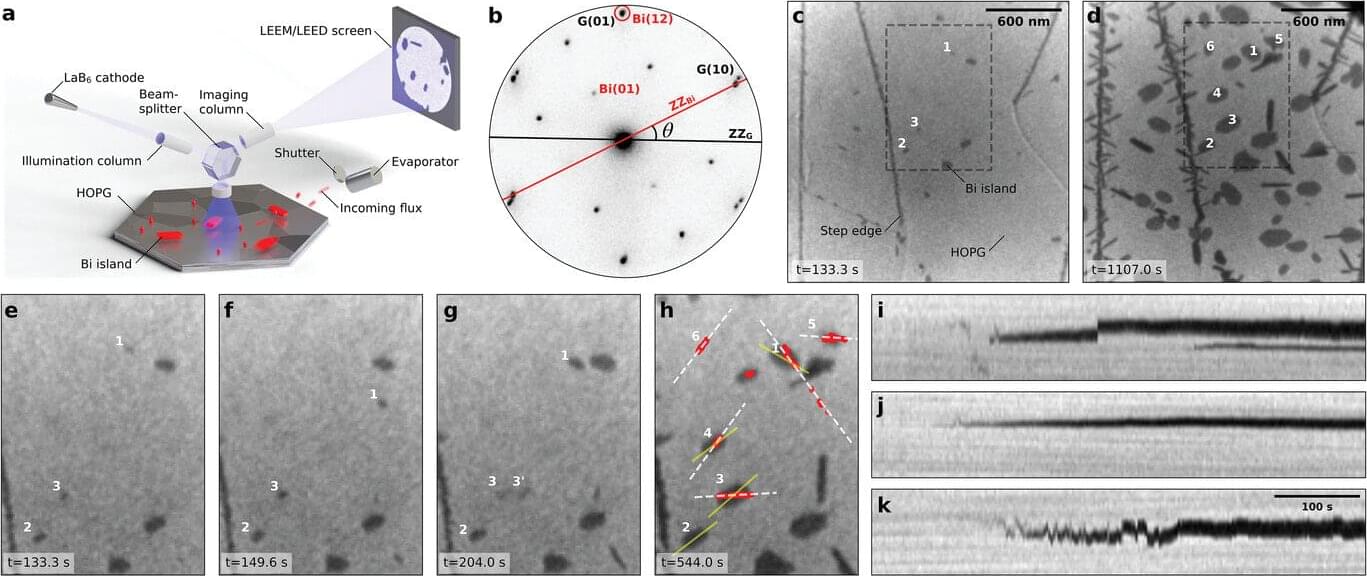

Scientists from the Faculty of Physics and Applied Informatics at the University of Lodz have published an article on friction in the journal Small. Their research on “bismuth islands” moving on the surface of graphite confirmed the existence of a totally new form of so-called superlubricity—a friction-free contact between two solid bodies.

This discovery could revolutionize the way we design nanoscale machines, and even vehicles, in the future. By understanding these processes, we can create devices that can operate much more efficiently, saving on energy and resources.

Scientists led by Dr. Hab. Paweł Kowalczyk, associate professor at the University of Lodz, have discovered a new phenomenon related to the disappearance of friction—superlubricity. This special phenomenon was observed at the contact of two solid materials, bismuth and graphite.

Amazon’s warehouses are a paradox of order and chaos, where robots like Vulcan strive to match human efficiency in picking items from cluttered bins. Can AI truly master the art of ‘bin etiquette’ and revolutionize warehouse operations?

A team of Harvard researchers have unveiled a way to map the molecular underpinnings of how learning and memories are formed, a new technique expected to offer insights that may pave the way for new treatments for neurological disorders such as dementia.

“This technique provides a lens into the synaptic architecture of memory, something previously unattainable in such detail,” said Adam Cohen, professor of chemistry and chemical biology and of physics and senior co-author of the research paper, published in Nature Neuroscience.

Memory resides within a dense network of billions of neurons within the brain. We rely on synaptic plasticity—the strengthening and modulation of connections between these neurons—to facilitate learning and memory.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology’s new cesium fountain clock is one of the most precise atomic clocks ever created.

Every week quantum computing hits a new milestone: more qubits, fewer errors, better readout of results. But will these breakthroughs help solve the advanced computational problems facing energy, like how to model energy storage catalysts or ensure power grid reliability? That is what scientists at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) want to know.

Working with local quantum companies, an NREL team is developing benchmarks for quantum computers on the problems that are important to energy science. The pursuit of benchmarks will allow NREL and industry to prioritize practical utility for the next generation of quantum software and hardware.

The first nonverbal patient to receive Elon Musk’s Neuralink shares a video he edited and narrated using his brain chip

Posted in biotech/medical, computing, Elon Musk, neuroscience | Leave a Comment on The first nonverbal patient to receive Elon Musk’s Neuralink shares a video he edited and narrated using his brain chip

The first nonverbal Neuralink patient to receive the chip implant is offering a glimpse into how he uses the technology — editing and narrating a YouTube video using signals from his brain.

Brad Smith is the third person in the world to get a brain chip implant with Elon Musk’s Neuralink, and the first person with ALS to do so.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects motor neurons — the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movement. Over time, patients lose voluntary control of muscle movements, affecting their ability to speak, eat, move, and breathe independently.

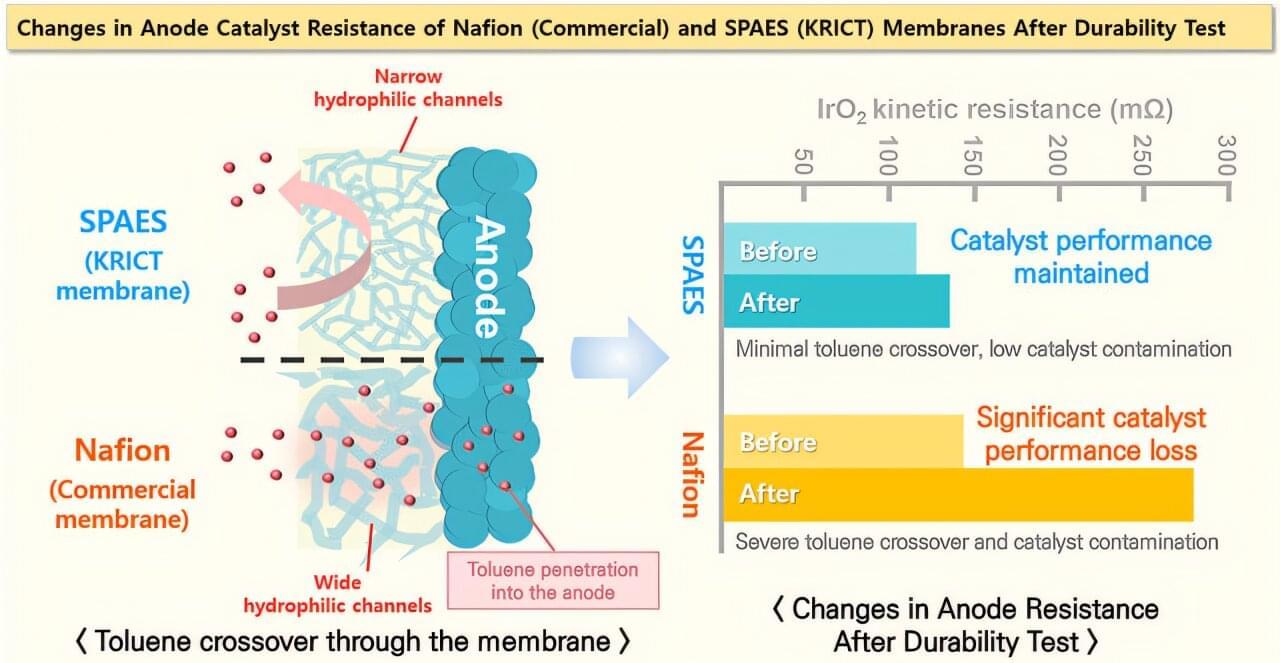

A Korean research team has developed a new proton exchange membrane (PEM) that significantly enhances the performance of electrochemical hydrogen storage systems. The work was published as a cover article in the Journal of Materials Chemistry A.

Dr. Soonyong So of the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT) and Professor Sang-Young Lee of Yonsei University have developed a next-generation PEM for LOHC-based electrochemical hydrogen storage using a hydrocarbon-based polymer called SPAES (sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone)).

This SPAES membrane reduces toluene permeability by over 60% compared to the commercially available perfluorinated PEM Nafion and improves the Faradaic efficiency of hydrogenation to 72.8%.

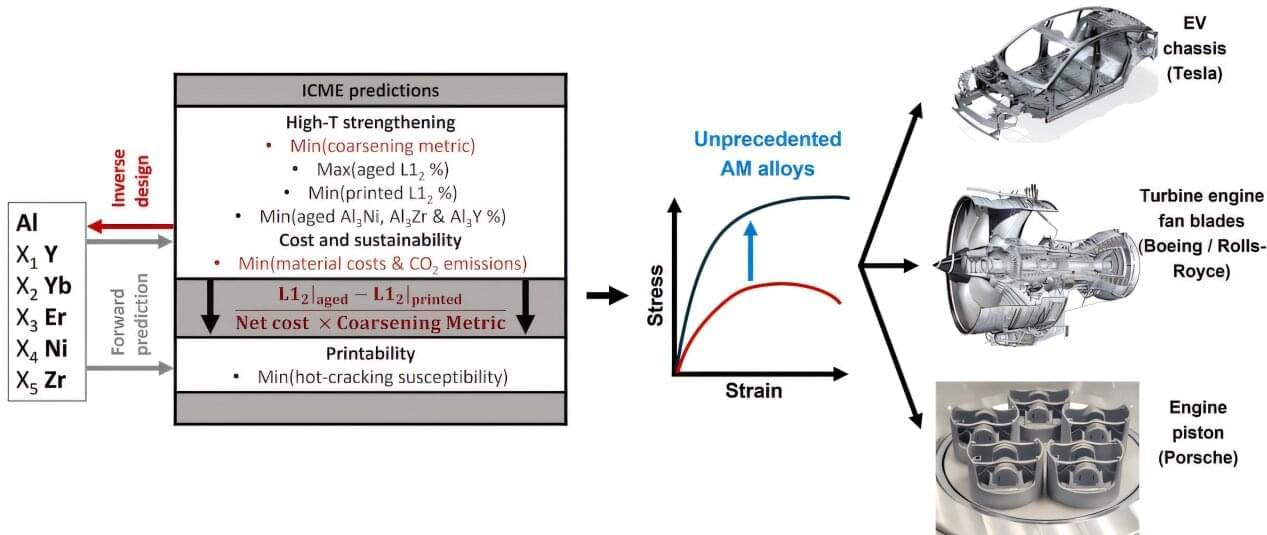

Aluminum alloys are widely used in transportation applications because of their high strength-to-weight ratio, as well as their affordability. However, challenges arise when using them in extremely high-strength and high-temperature applications, particularly in components such as pistons of combustion engines, fan blades of jet engines, and vacuum pumps.

At elevated temperatures, few aluminum alloys can block dislocation movements effectively, which controls the strength. Moreover, few of the designs have considered costs and sustainability metrics in the design, which are essential for high-demand industries. Titanium alloys, such as Ti-64, that are often used in fan blades, are not only heavier and not machinable, but also nearly twice as expensive.

Additive manufacturing (AM) is rapidly evolving and providing new pathways for designing innovative alloys. A recent study by Carnegie Mellon University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers has utilized computational simulations and optimization techniques to identify a new aluminum alloy system that balances strength and cost.

It’s spring, the birds are migrating and bird flu (H5N1) is rapidly evolving into the possibility of a human pandemic. Researchers from the University of Maryland School of Public Health have published a comprehensive review documenting research on bird flu in cats and calling for urgent surveillance of cats to help avoid human-to-human transmission.

The work is published in the journal Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

“The virus has evolved, and the way that it jumps between species—from birds to cats, and now between cows and cats, cats and humans—is very concerning. As summer approaches, we are anticipating cases on farms and in the wild to rise again,” says lead and senior author Dr. Kristen Coleman, assistant professor in UMD School of Public Health’s Department of Global, Environmental and Occupational Health and affiliate professor in UMD’s Department of Veterinary Medicine.