From VR at the Las Vegas Sphere to AI trained on synthetic children’s stories, check out this week’s awesome tech stories from around the web.

The brain is an evolutionary marvel. By shifting the control of sensing and behavior to this central organ, animals (including us) are able to flexibly respond and flourish in unpredictable environments. One skill above all—learning—has proven key to the good life.

But what of all the organisms that lack this precious organ? From jellyfish and corals to our plant, fungi, and single-celled neighbors (such as bacteria), the pressure to live and reproduce is no less intense, and the value of learning is undiminished.

Recent research on the brainless has probed the murky origins and inner workings of cognition itself, and is forcing us to rethink what it means to learn.

On Monday, Waymo announced on X that it’s expanding its city-wide, fully autonomous robotaxi service to thousands more riders in San Francisco.

The company had been testing a service area of nearly the whole city (around 47 square miles) with employees and, later, a group of test riders. But most people using the service were precluded from riding in the city’s dense northeast corner, an area including Fisherman’s Wharf, the Embarcadero, and Chinatown.

Now, the full San Francisco service area will be available to all current Waymo One users—amounting to tens of thousands of people, according to TechCrunch. While it’s a significant increase, not just anyone can use Waymo in SF yet. The company has been growing the service by admitting new riders from a waitlist that numbered 100,000 in June.

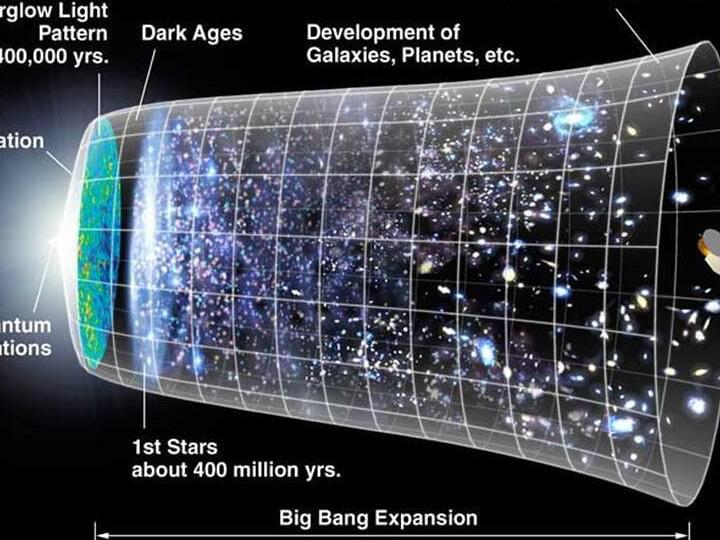

From the vast expanse of galaxies that paint our night skies to the intricate neural networks within our brains, everything we know and see can trace its origins back to a singular moment: the Big Bang. It’s a concept that has not only reshaped our understanding of the universe but also offers profound insights into the interconnectedness of all existence.

Imagine, if you will, the entire universe compressed into an infinitesimally small point. This is not a realm of science fiction but the reality of our cosmic beginnings. Around 13.8 billion years ago, a singular explosion gave birth to time, space, matter, and energy. And in that magnificent burst of creation, the seeds for everything — galaxies, stars, planets, and even us — were sown.

But what if the Big Bang was not just a physical event? What if it also marked the birth of a universal consciousness? A consciousness that binds every particle, every star, and every living being in a cosmic tapestry of shared experience and memory.

Although climate change and global warming affect countries all over the world, Iraq has been hit especially hard. Temperatures are rising twice as fast and annual rainfall is decreasing, leaving the country struggling with many severe droughts. However, the lower water levels of the Euphrates River during these droughts allowed the secrets of a forgotten civilization to emerge. Join us as we embark on an extraordinary journey to discover the ancient ruins found under the Euphrates River!

In 2018, a terrible drought in Iraq left the water levels of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers dangerously low. In an effort to help the country, the Mosul Dam Reservoir in the Kurdistan region was drained, providing much-needed water to dying crops. But, as the reservoir’s water receded, the ruins of an ancient city suddenly emerged!

Racing against time, archaeologists diligently worked to explore and map out the newly-exposed ancient ruins before the water covered them once again. They discovered the ruins of a large palace with 22-foot tall walls, some of which were 6 feet thick! Many of the walls were also adorned with well-preserved wall paintings, shining bright with their blue and red hues. The palace, built in two distinct phases, had been used over a long period of time and may hold many of the secrets of the mighty Mitanni Empire. However, before they could evaluate it further, the palace and the rest of the city resubmerged beneath the Euphrates River, leaving their mysteries unresolved for the next four years.

A sealed tomb featuring a fresco of Cerberus – the three-headed dog from Ancient Greek mythology – has been uncovered in Italy.

The burial chamber was discovered in Giugliano, a suburb of Naples, and is believed to be some 2,000 years old.

It was found on farmland during an archaeological survey carried out prior to the start of maintenance work on the city’s water system.

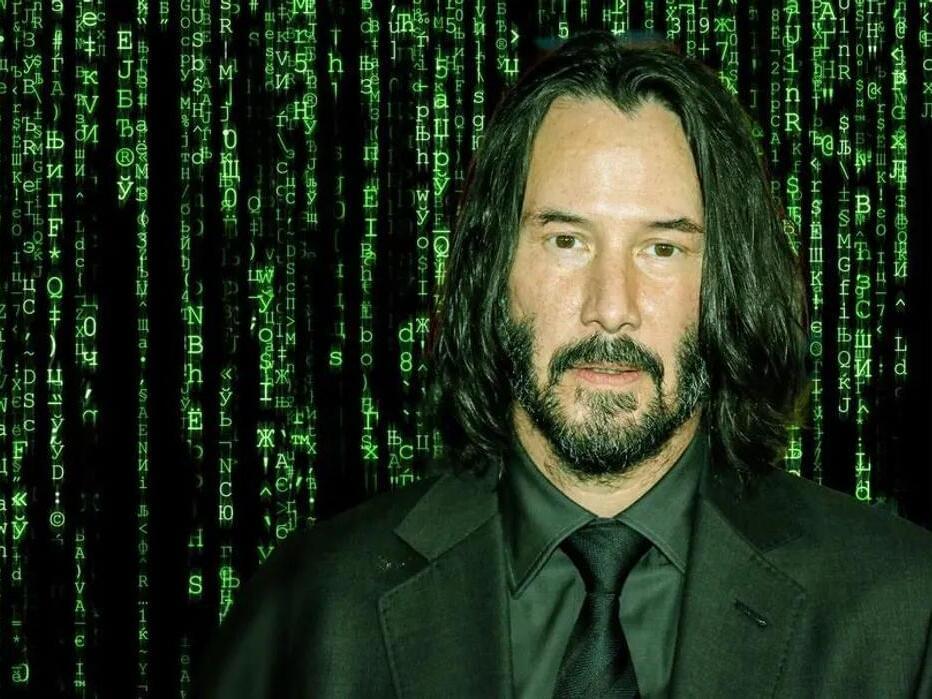

“ The Matrix is everywhere. It is all around us. Even now in this very room. ”

So says Laurence Fishburne’s Morpheus in sci-fi classic ‘ The Matrix ’ as he offers Keanu Reeves’s Neo the choice to find out just how “deep the rabbit hole goes”.

Now, just as Neo discovered that the “life” he’d been living was little more than an algorithmic construct, scientists and philosophers are arguing that we could be stuck inside a simulation ourselves.

Given these perks, it’s no wonder scientists have tried recreating skin in the lab. Artificial skin could, for example, cover robots or prosthetics to give them the ability to “feel” temperature, touch, or even heal when damaged.

It could also be a lifesaver. The skin’s self-healing powers have limits. People who suffer from severe burns often need a skin transplant taken from another body part. While effective, the procedure is painful and increases the chances of infection. In some cases, there might not be enough undamaged skin left. A similar dilemma haunts soldiers wounded in battle or those with inherited skin disorders.

Recreating all the skin’s superpowers is tough, to say the least. But last week, a team from Wake Forest University took a large step towards artificial skin that heals large wounds when transplanted into mice and pigs.

Event Timing: Thursday, October 26, 2023 | Doors open at 6 PM | Service commence at 7 PM. Event Address: Perpetual Life 950 South Cypress Road, Pompano Beach, FL 33,060 Contact us: [email protected] Zoom Registration: Register Now.