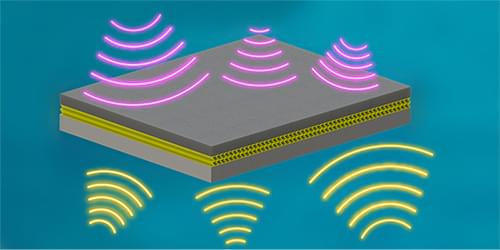

A lightweight structure made of rubber and metal layers can provide an object with underwater acoustic stealth over a broad frequency range.

An acoustic “cloak” could hide an underwater object from detection by sonar devices or by echolocating marine animals. Much like camouflage clothing allows figures to fade into a background, acoustic camouflage can make an object indistinguishable from the surrounding water. Underwater acoustic cloaks have previously been demonstrated, but they typically work over a narrow range of frequencies or are too bulky to be practical. Now Hao-Wen Dong at the Beijing Institute of Technology and colleagues demonstrate a lightweight, broadband cloak made of a thin shell of layered material. The cloak achieves acoustic stealth by both blocking the reflection of sonar pings off the surface and preventing the escape of sound generated from within the cloaked object [1].

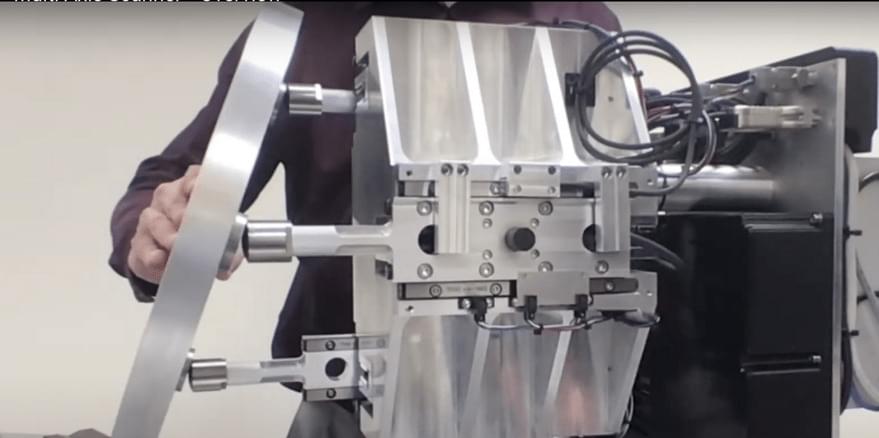

Dong and colleagues designed a 4-cm-thick structure—combining an outer rubber layer and a “metamaterial” made of porous aluminum—which covered a steel plate. Using a genetic algorithm, they optimized the metamaterial’s elastic properties to tailor the interaction with underwater sound waves. Specifically, the metamaterial converts impinging longitudinal sound waves, which can travel long distances underwater, to transverse sound waves, which cannot propagate through water. These transverse waves get trapped in the rubber layer, where they get absorbed, eliminating reflected and transmitted waves simultaneously. The researchers built and tested a prototype cloak, confirming that it behaved as predicted. In particular, it absorbed 80% of the energy of incoming sound waves while offering 100-fold attenuation of acoustic noise produced on the side of the steel plate.