You’ll get all of the video & audio recordings (so you can listen and watch whenever you want), as well as the transcripts and learning tools.

4.25 CE/CME Credits or Clock Hours are available for purchase at checkout.

You’ll get all of the video & audio recordings (so you can listen and watch whenever you want), as well as the transcripts and learning tools.

4.25 CE/CME Credits or Clock Hours are available for purchase at checkout.

Richard Mansell, Chief Executive Officer at IVO Limited gave the reasons he is optimistic about the Quantum Space Drive tests that will be done in orbital microgravity.

IF the orbital test works then it will lead to interstellar travel and shrinking it down would give material that would have anti-gravity like effects. We would spend the money to make nanocavities so that we could have propellantless thrust for floating cities. All of space and propulsion related science fiction would become possible within about three decades short of faster than light. This drive is in orbit now for a few months. I think DARPA gave them more money to conclusively prove if it works or not. All of the ground tests show it might work. But if it proves out then we first get 1,000 times better than a hall effect thruster but with no fuel limit. No fuel is used. So long as you have power, solar or nuclear the drive keeps working. So nuclear fuel supply for decades then thrust for decades. The theory proves out, then we make nanocavities which could act like antigravity then we get 1G or even 3G thrusters in space. This would be the Expanse TV show tech.

Summary: Researchers identified cortical gray matter thinning as a potential early biomarker for dementia. In a study involving 1,500 participants from diverse backgrounds, thinner cortical gray matter was linked to a higher risk of developing dementia 5 to 10 years before symptoms appeared.

This finding suggests that measuring gray matter thickness via MRI could be key in early dementia detection and intervention. The research highlights the importance of early diagnosis in managing and possibly slowing the progression of dementia.

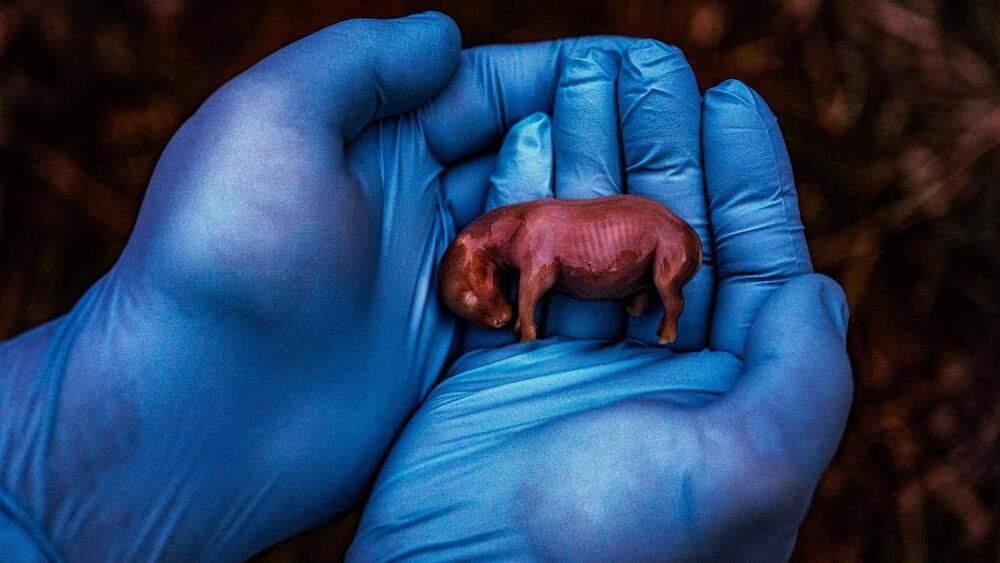

Scientists have cleared a significant hurdle in the years-long effort to save Africa’s northern white rhinoceros from extinction with the first-ever rhino pregnancy using in vitro fertilization.

A new medical breakthrough with embryo transfer offers hope for Africa’s northern white rhinos—there are only two left.

If you give a rat a camera, it will apparently take selfies.

That was the biggest takeaway from a fresh riff on a classic rat experiment undertaken by French photographer and amateur behaviorist Augustin Lignier, who told the New York Times that when he taught some pet store rats how to take selfies using a lever that snapped a pic and rewarded them with some sugar, the photo-snapping continued even after the treats stopped.

Born from a desire to understand why people take and post so many self-portraits online, Lignier designed a modified version of behaviorist B.F. Skinner’s conditioning experiments wherein rats were given food for pushing a button inside a box. Known now as the “Skinner box,” this groundbreaking methodology developed in the 1930s has been used repeatedly in the past century not just to study behavior but also as an allegory — and has even served to describe humans’ relationship to social media.

People with long COVID have dysfunctional immune cells that show signs of chronic inflammation and faulty movement into organs, among other unusual activity, according to a new study by scientists at Gladstone Institutes and UC San Francisco (UCSF).

The team analyzed immune cells and hundreds of different immune molecules in the blood of 43 people with and without long COVID. They delved particularly deep into the characteristics of each person’s T cells—immune cells that help fight viral infections but can also trigger chronic inflammatory diseases.

Their findings, which appear in Nature Immunology, support the hypothesis that long COVID may involve a low-level viral persistence. The study also reveals a mismatch between the activity of T cells and other components of the immune system in people with long-term COVID-19.

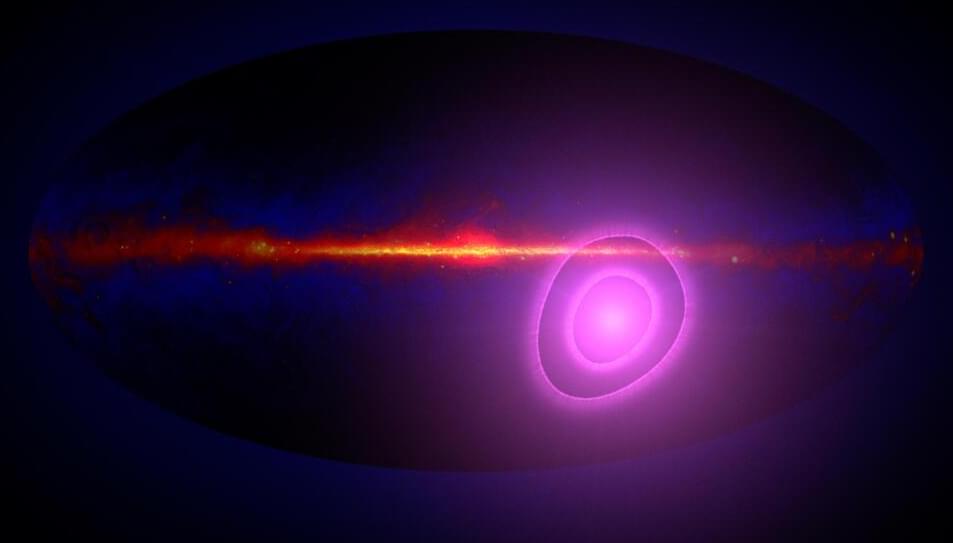

Astronomers analyzing 13 years of data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope have found an unexpected and as yet unexplained feature outside of our galaxy.

“It is a completely serendipitous discovery,” said Alexander Kashlinsky, a cosmologist at the University of Maryland and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, who presented the research at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in New Orleans. “We found a much stronger signal, and in a different part of the sky, than the one we were looking for.”

Intriguingly, the gamma-ray signal is found in a similar direction and with a nearly identical magnitude as another unexplained feature, one produced by some of the most energetic cosmic particles ever detected.

Summary: Researchers made a significant discovery using an artificial neural network model, suggesting that musical instinct may emerge naturally from the human brain. By analyzing various natural sounds through Google’s AudioSet, the team found that certain neurons in the network selectively responded to music, mimicking the behavior of the auditory cortex in real brains.

This spontaneous generation of music-selective neurons indicates that our ability to process music may be an innate cognitive function, formed as an evolutionary adaptation to better process sounds from nature.