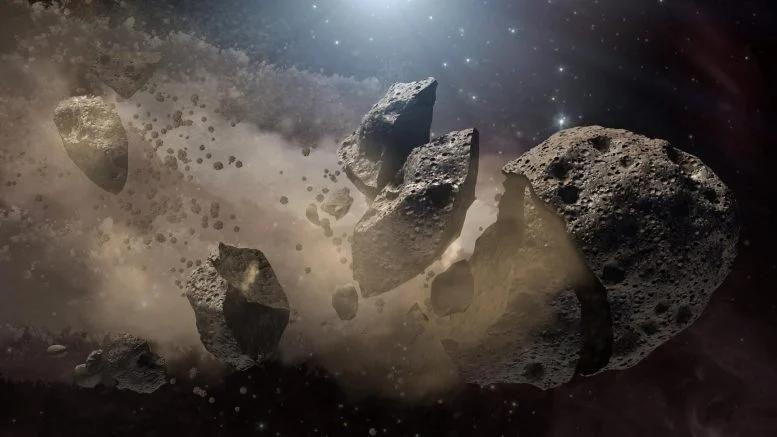

I found this on NewsBreak: New models of Big Bang show that visible universe and invisible dark matter co-evolved.

Physicists have long theorized that our universe may not be limited to what we can see. By observing gravitational forces on other galaxies, they’ve hypothesized the existence of “dark matter,” which would be invisible to conventional forms of observation.