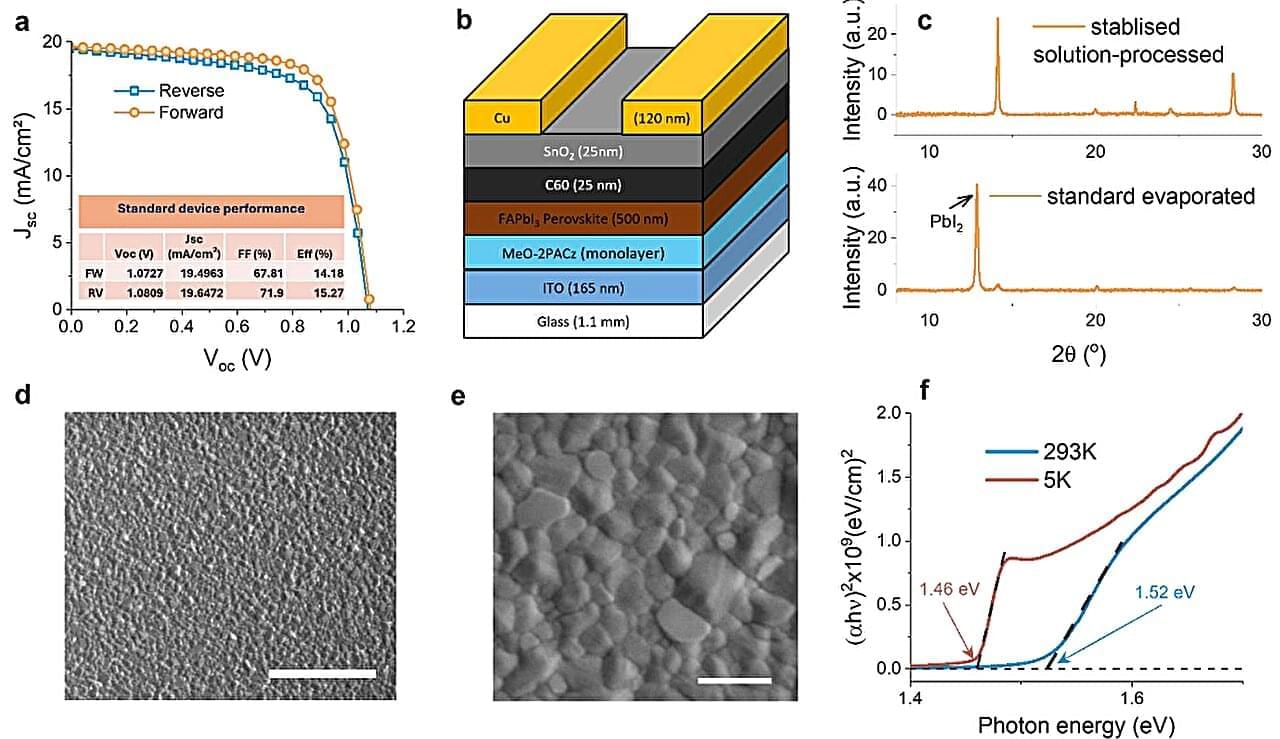

A research team, led by Professor Heein Yoon in the Department of Electrical Engineering at UNIST has unveiled an ultra-small hybrid low-dropout regulator (LDO) that promises to advance power management in advanced semiconductor devices. This innovative chip not only stabilizes voltage more effectively, but also filters out noise—all while taking up less space—opening new doors for high-performance system-on-chips (SoCs) used in AI, 6G communications, and beyond.

The new LDO combines analog and digital circuit strengths in a hybrid design, ensuring stable power delivery even during sudden changes in current demand—like when launching a game on your smartphone—and effectively blocking unwanted noise from the power supply.

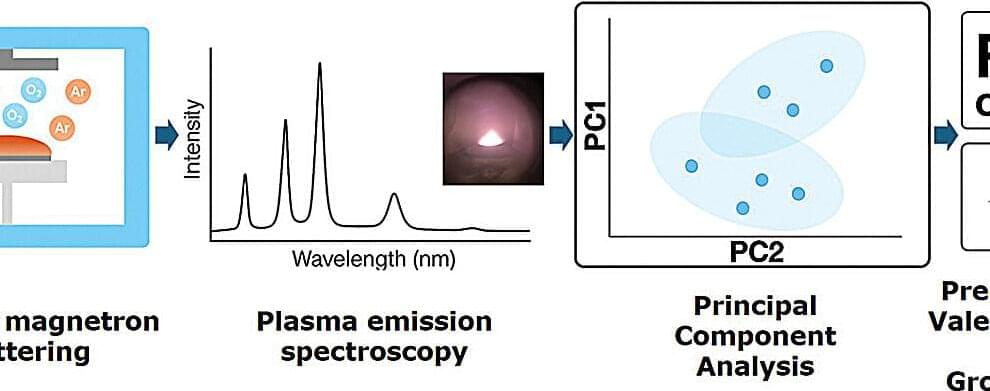

What sets this development apart is its use of a cutting-edge digital-to-analog transfer (D2A-TF) method and a local ground generator (LGG), which work together to deliver exceptional voltage stability and noise suppression. In tests, it kept voltage ripple to just 54 millivolts during rapid 99 mA current swings and managed to restore the voltage to its proper level in just 667 nanoseconds. Plus, it achieved a power supply rejection ratio (PSRR) of −53.7 dB at 10 kHz with a 100 mA load, meaning it can effectively filter out nearly all noise at that frequency.