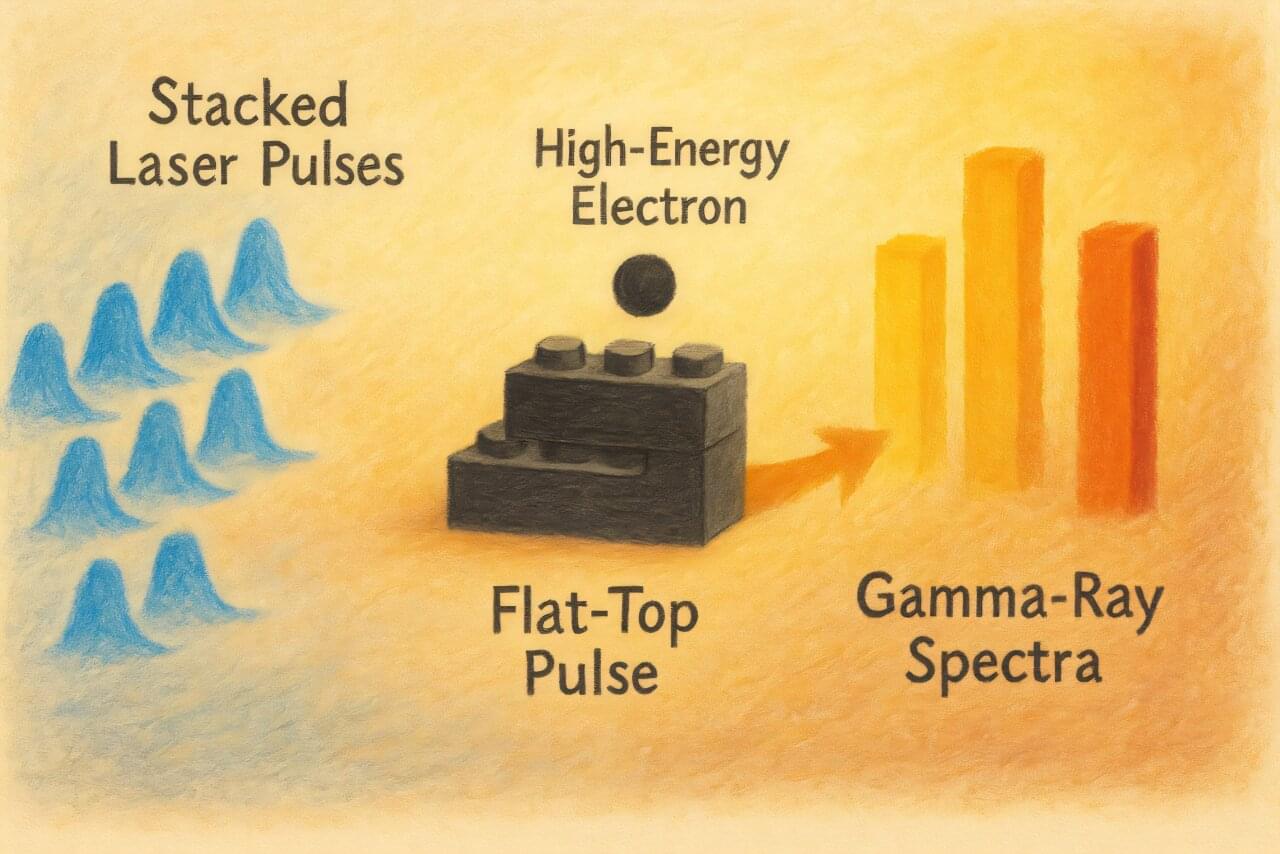

Researchers from Skoltech, MEPhI, and the Dukhov All-Russian Research Institute of Automation have proposed a new method to create compact gamma-ray sources that are simultaneously brighter, sharper, and capable of emitting multiple “colors” of gamma rays at once.

This opens up possibilities for more accurate medical diagnostics, improved material inspection, and even the production of isotopes for medicine directly in the laboratory. The work has been published as a Letter in the journal Physical Review A.

Gamma rays produced using lasers and electron beams represent a promising technology, but until now they have had a significant drawback: the emission spectrum was too “blurred.” This reduced brightness and precision, limiting their applications in areas where clarity is crucial—such as scanning dense materials or medical imaging.