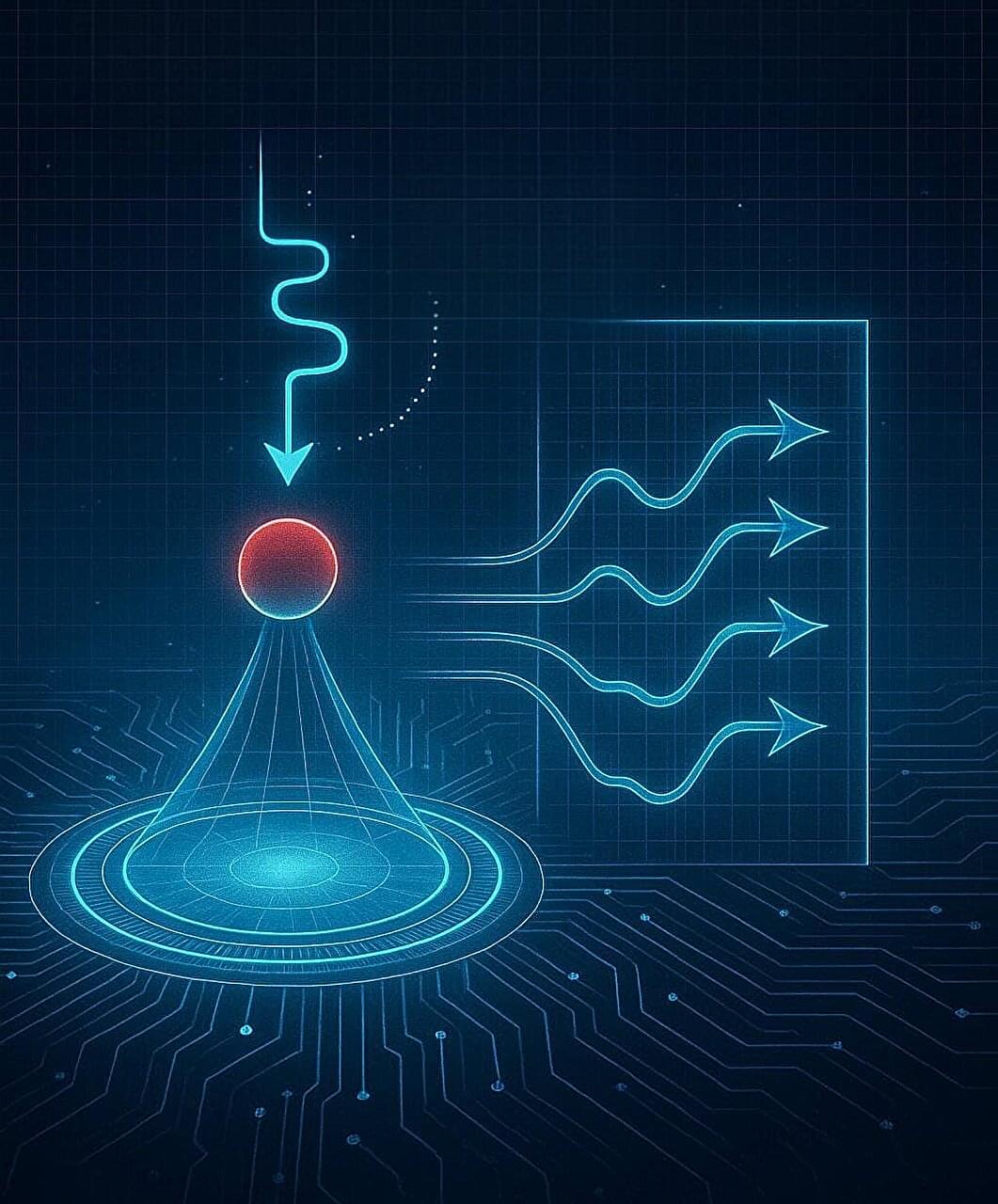

A radio-frequency field can be resonant with nuclear spins in a sample even if its frequency does not match a spectroscopic transition—a result that could enable new forms of NMR spectroscopy.

Physical systems often have characteristic frequencies. When excited at such a frequency, they start to resonate. The Broughton Suspension Bridge incident on April 12, 1831, showed how this can go wrong. A detachment of 74 riflemen marched in step over the bridge, accidentally matching its resonance frequency. Before they had crossed, the bridge collapsed. At the much-smaller scale of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, resonant excitation is less dramatic yet very useful. Typically, NMR relies on secular resonance, which occurs when the energy of the radio-frequency photons used in a measurement matches the energy required for flipping the magnetic moment of a nucleus in a static magnetic field. This secular resonance occurs at the so-called Larmor frequency. Structure determination of chemical compounds, experimental observation of protein dynamics, and magnetic resonance imaging rely on this matching.