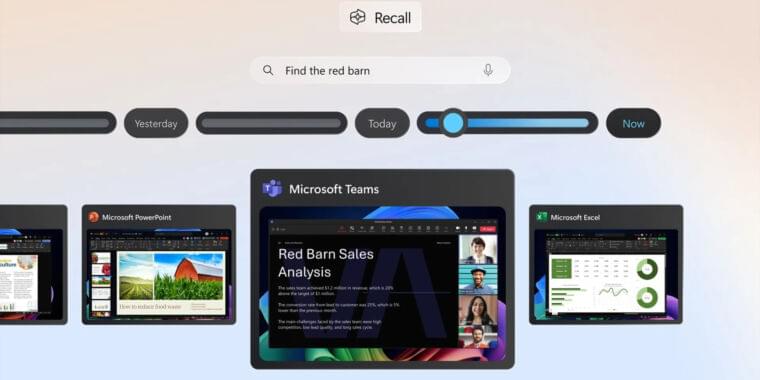

“Recall uses Copilot+ PC advanced processing capabilities to take images of your active screen every few seconds,” Microsoft says on its website. “The snapshots are encrypted and saved on your PC’s hard drive. You can use Recall to locate the content you have viewed on your PC using search or on a timeline bar that allows you to scroll through your snapshots.”

By performing a Recall action, users can access a snapshot from a specific time period, providing context for the event or moment they are searching for. It also allows users to search through teleconference meetings they’ve participated in and videos watched using an AI-powered feature that transcribes and translates speech.

At first glance, the Recall feature seems like it may set the stage for potential gross violations of user privacy. Despite reassurances from Microsoft, that impression persists for second and third glances as well. For example, someone with access to your Windows account could potentially use Recall to see everything you’ve been doing recently on your PC, which might extend beyond the embarrassing implications of pornography viewing and actually threaten the lives of journalists or perceived enemies of the state.