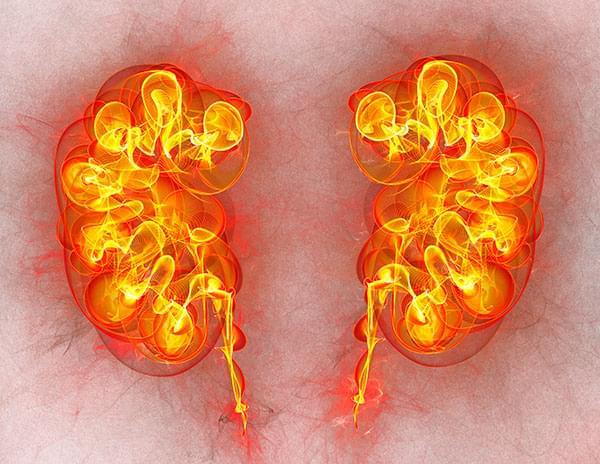

A new study from Aarhus University demonstrates that a protein known for treating cardiovascular diseases also affects a mechanism in the kidney that reabsorbs proteins. This finding could lead to new treatment options for chronic kidney disease.

The new study is published in Kidney International in an article titled, “Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 targets megalin in the kidney proximal tubule and aggravates proteinuria in nephrotic syndrome.”

“Proteinuria is a prominent feature of chronic kidney disease,” wrote the researchers. “Interventions that reduce proteinuria slow the progression of chronic kidney disease and the associated risk of cardiovascular disease. Here, we propose a mechanistic coupling between proteinuria and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), a regulator of cholesterol and a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease.”