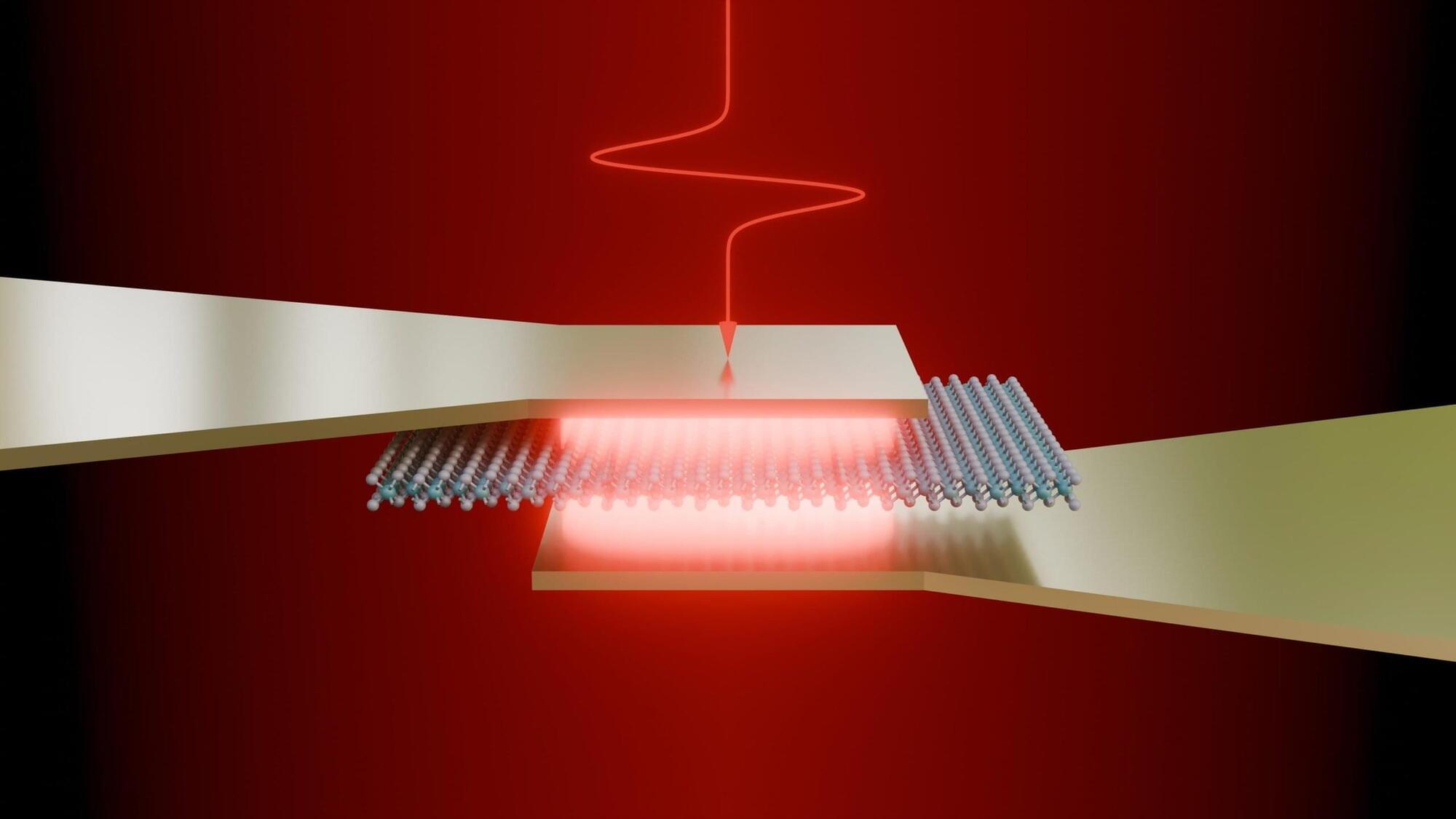

What if particles don’t slow down in a crowd, but move faster? Physicists from Leiden worked together and discovered a new state of matter, where particles pass on energy through collisions and create more movement when packed closely together.

We all know crowds of people, or cars in a traffic jam—when it gets too crowded, all you can do is stand still. Until now, scientists have mainly studied cases of large groups just like this, which slow down when they get too close to each other.

But what if the opposite happens? What if particles could start moving more when packed together? That question hadn’t been studied much—until now. Physicists Marine Le Blay, Joshua Saldi and Alexandre Morin from Leiden University do research in the field of active matter physics—they observe and analyze the collective behaviors that emerge when large groups of particles are packed together.