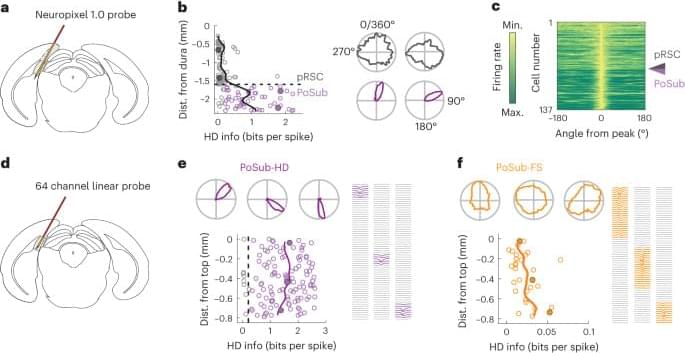

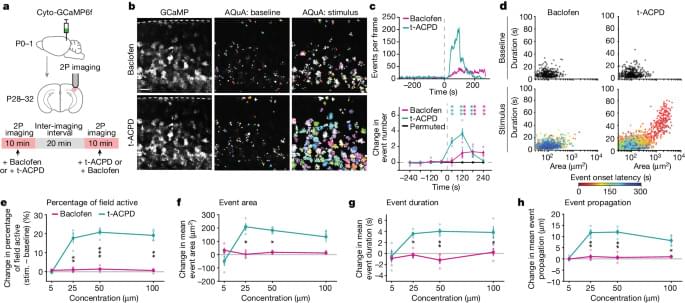

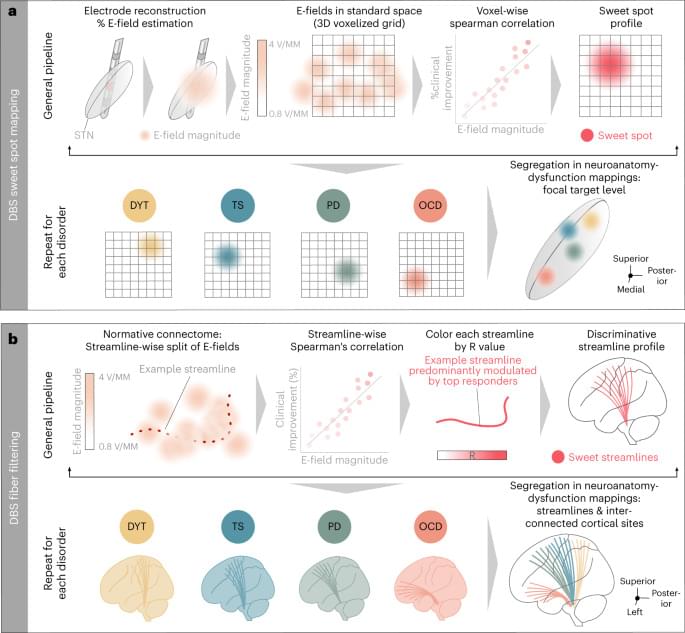

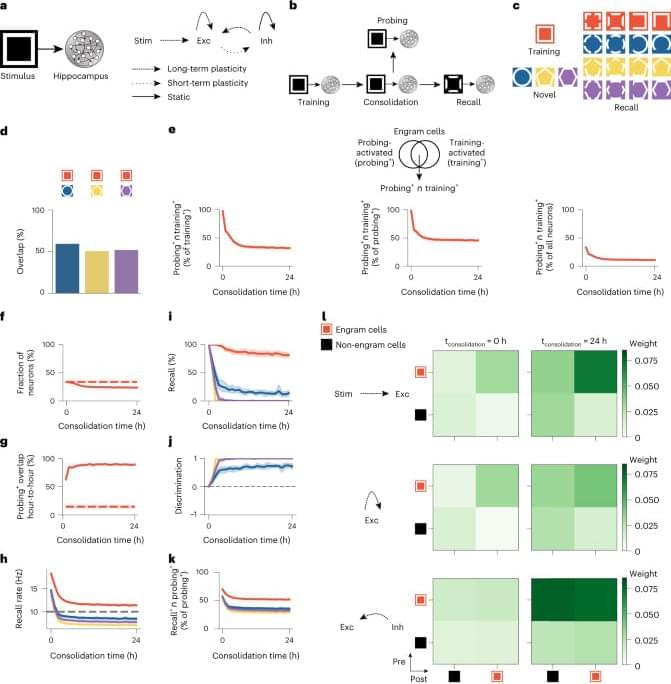

The changes in engram composition and selectivity observed in our model were associated with ongoing synaptic plasticity during memory consolidation (Fig. 1l). Feedforward synapses from training stimulus neurons (that is, sensory engram cells; Methods) onto hippocampal engram cells were strengthened over the course of memory consolidation, and, consequently, the synaptic coupling between the stimulus population and the hippocampus network was increased. Recurrent excitatory synapses between engram cells also experienced a modest gain in synaptic efficacy. Notably, inhibitory synapses from inhibitory engram cells onto both engram and non-engram cells were strongly potentiated throughout memory consolidation. This indicated that a number of training-activated engram cells were forced out of the engram due to strong inhibition, and, consequently, only neurons highly responsive to the training stimulus remained in the engram, in line with our previous analysis (Fig. 1e). Inhibitory neurons also controlled the overall activity of excitatory neurons in the network through inhibitory synaptic plasticity (Extended Data Fig. 2h).

To investigate the contribution of synaptic plasticity to the engram dynamics in our model, we performed several manipulations in our simulations. First, we blocked the reactivation of the training stimulus during memory consolidation and found that this altered the temporal profile of engrams and prevented them from becoming selective (Extended Data Fig. 3a–i). These effects were associated with reduced potentiation of inhibitory synapses onto engram cells (compare Extended Data Fig. 3i to Fig. 1l, bottom rows). Previous experiments demonstrated that sleep-specific inhibition of learning-activated sensory neurons disrupts memory selectivity11, and, hence, our model was consistent with these findings, and it predicted underlying mechanisms. Second, blocking long-term potentiation (LTP) during memory consolidation almost completely eliminated engram cell turnover after a steady state was reached, and it also impaired memory recall relative to the control case (Extended Data Fig. 4a–i). Reduced feedforward and recurrent excitatory synaptic weights due to LTP blockage led to engram stabilization and impaired recall (compare Extended Data Fig. 4h to Fig. 1l, top and middle rows). These results are in line with a recent study showing that memory recall is impaired when LTP is optically erased selectively during sleep14. Third, we separately blocked the Hebbian and non-Hebbian forms of long-term excitatory synaptic plasticity in our model and verified that each was essential for memory encoding and consolidation (Extended Data Fig. 5). These results are consistent with a previously reported mean-field analysis showing that this combination of plasticity mechanisms can support stable memory formation and recall9. Fourth, we blocked inhibitory synaptic plasticity in our entire simulation protocol, and this disrupted the emergence of memory selectivity in our network model (Extended Data Fig. 6a–h). This demonstrated that excitatory synaptic plasticity alone could not drive an increase in memory selectivity because it could not increase competition among excitatory neurons in the absence of inhibitory synaptic plasticity (compare Extended Data Fig. 6h to Fig. 1l). However, excitatory synaptic plasticity could promote engram cell turnover on its own in an even more pronounced manner than in the presence of both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic plasticity (compare Extended Data Fig. 6b to Fig. 1g). Finally, we found that an alternative inhibitory synaptic plasticity formulation yielded engram dynamics analogous to those in our original network (compare Extended Data Fig. 7a–h to Fig. 1e–l). This suggested that the dynamic and selective engrams predicted by our model are not a product of a specific form of inhibitory plasticity but a consequence of memory encoding and consolidation in inhibition-stabilized plastic networks in general.

We also conduced loss-of-function and gain-of-function manipulations to examine the role of training-activated engram cells in memory recall in our model (Fig. 2). We found that blocking training-activated engram cells after a consolidation period of 24 h prevented memory recall (Fig. 2a), whereas artificially reactivating them in the absence of retrieval cues was able to elicit recall (Fig. 2b), in a manner consistent with previous experimental findings3,4 and despite the dynamic nature of engrams in our simulations (Fig. 1e–g). Thus, our model was able to reconcile the prominent role of training-activated engram cells in memory storage and retrieval with dynamic memory engrams. To determine whether neuronal activity during memory acquisition was predictive of neurons dropping out of or dropping into the engram, we examined the distribution of stimulus-evoked neuronal firing rates in the training phase (Extended Data Fig. 3j–m). We found that training-activated engram cells that remained part of the engram throughout memory consolidation exhibited higher stimulus-evoked firing rates than the remaining neurons in the network (Extended Data Fig. 3j) and training-activated engram cells that dropped out of the engram over the course of consolidation (Extended Data Fig. 3k). Therefore, stimulus-evoked firing rates during training were indicative of a neuron’s ability to outlast inhibition and remain part of the engram after initial memory encoding. We also verified that neurons that were not engram cells at the end of training but later dropped into the engram displayed lower training stimulus-evoked firing rates than the remaining neurons in the network (Extended Data Fig. 3l). Surprisingly, neurons that dropped into the engram after training showed slightly lower stimulus-evoked firing rates than neurons that failed to become part of the engram altogether (Extended Data Fig. 3m). This suggested that stimulus-evoked firing rates during memory acquisition may not be reliable predictors of a neuron’s ability to increase its response to the training stimulus and become an engram cell after encoding. Lastly, we found that using a neuronal population-based approach to identify engram cells in our simulations yielded analogous engram dynamics (compare Extended Data Fig. 4j–o to Fig. 1e−j and Extended Data Fig. 2i–n to Extended Data Fig. 2b−g; Methods).