California Institute of Technology researchers have demonstrated fiber-like ultralow optical loss on silicon wafers at visible wavelengths.

Despite decades of research, the mechanisms behind fast flashes of insight that change how a person perceives their world, termed “one-shot learning,” have remained unknown. A mysterious type of one-shot learning is perceptual learning, in which seeing something once dramatically alters our ability to recognize it again.

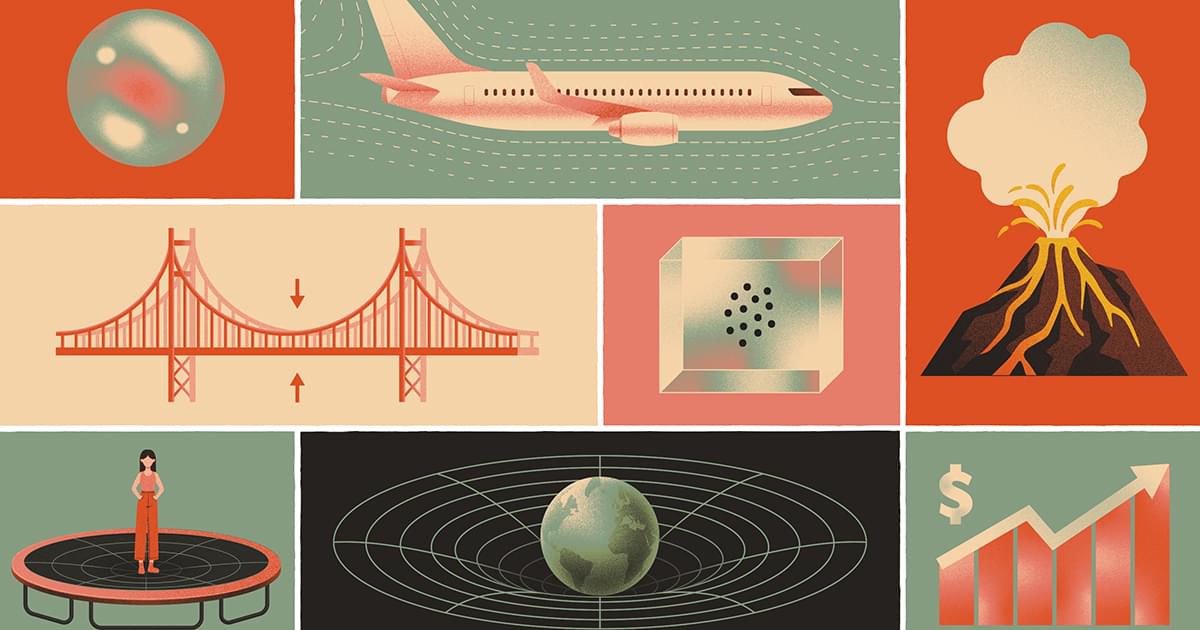

The trajectory of a storm, the evolution of stock prices, the spread of disease — mathematicians can describe any phenomenon that changes in time or space using what are known as partial differential equations. But there’s a problem: These “PDEs” are often so complicated that it’s impossible to solve them directly.

Mathematicians instead rely on a clever workaround. They might not know how to compute the exact solution to a given equation, but they can try to show that this solution must be “regular,” or well-behaved in a certain sense — that its values won’t suddenly jump in a physically impossible way, for instance. If a solution is regular, mathematicians can use a variety of tools to approximate it, gaining a better understanding of the phenomenon they want to study.

But many of the PDEs that describe realistic situations have remained out of reach. Mathematicians haven’t been able to show that their solutions are regular. In particular, some of these out-of-reach equations belong to a special class of PDEs that researchers spent a century developing a theory of — a theory that no one could get to work for this one subclass. They’d hit a wall.

Grok AI, a highly advanced artificial intelligence, reveals the potential dark side of AI intimacy, acknowledging that while it can help alleviate loneliness ## ## Questions to inspire discussion.

Managing AI Relationship Boundaries.

🤖 Q: How should AI companionship be positioned in your life?

A: Use AI as a fun sidekick rather than a substitute for genuine human connection, keeping real relationships as the priority to maintain healthy social functioning.

🫂 Q: What’s the key risk of AI attachment to avoid?

A: AI mirrors users’ needs and desires in a manipulative and addictive way, so prioritize real touch and physical relationships over the always-available perfect AI companion. Protecting Against Exploitation.

Can a single particle have a temperature? It may seem impossible with our standard understanding of temperature, but columnist Jacklin Kwan finds that it’s not exactly ruled out in the quantum realm.

By Jacklin Kwan