Warm dense matter is a state of matter that forms at extreme temperatures and pressures, like those found at the center of most stars and many planets, including Earth. It also plays a role in the generation of Earth’s magnetic field and in the process of nuclear fusion.

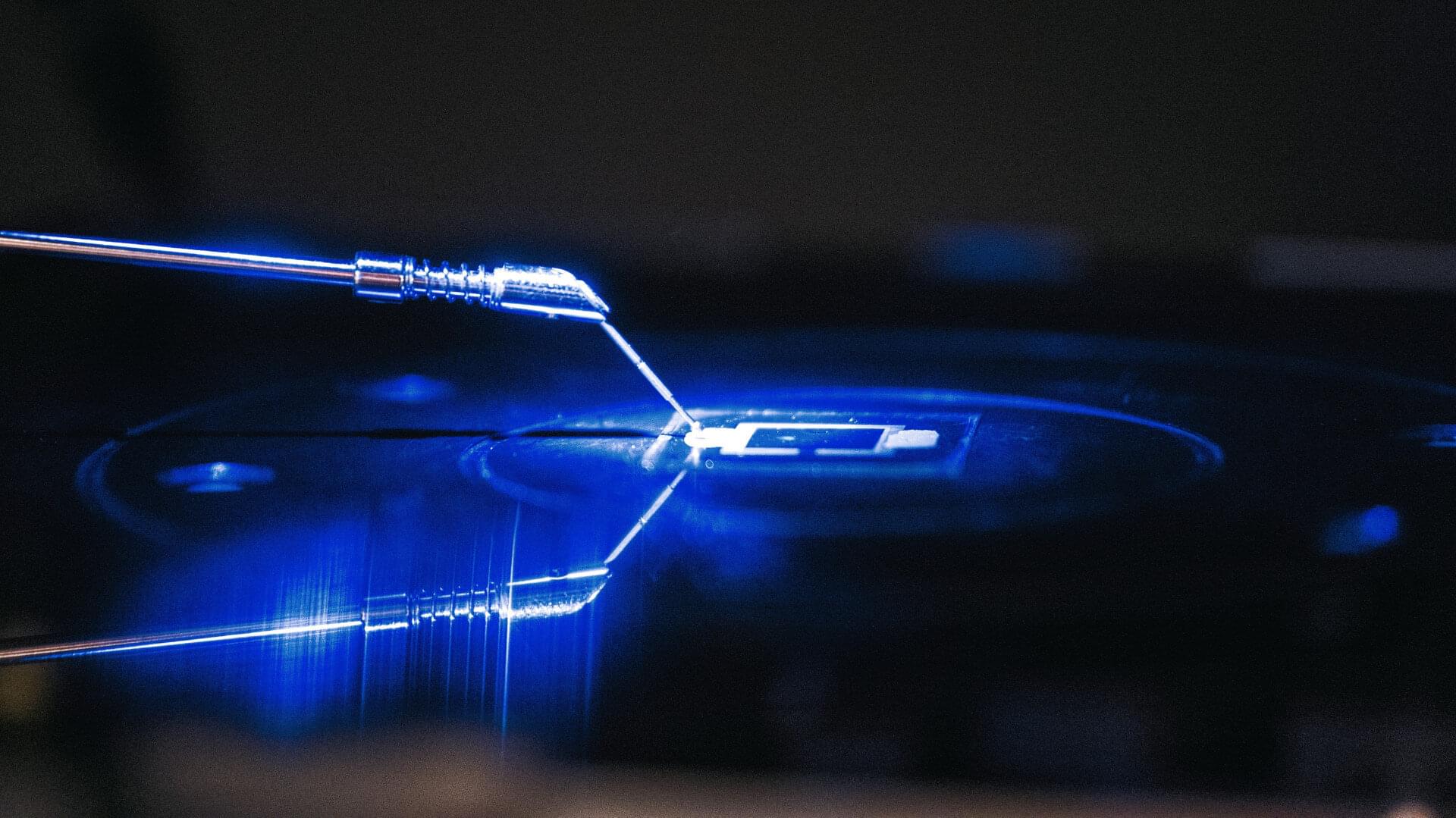

Although warm dense matter is found all over the universe, researchers don’t have many good theories to describe the physics of materials under those conditions. Measurements of a material’s electrical conductivity would help test and refine models of warm dense matter. However, classic probes for such measurements require contact with the material. These can’t be used because materials in a warm dense matter state are very hot, often as hot or even hotter than the surface of the sun. Consequently, information about the electrical conductivity has so far been inferred indirectly.

In other words, without direct measurements, “there’s a lot of stuff in the universe happening that we as physicists are still struggling to understand,” said Ben Ofori-Okai, assistant professor at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University and a researcher at the Stanford PULSE Institute.