Scientists at UBC Okanagan have revealed how plants create mitraphylline, a rare natural substance that shows potential for fighting cancer.

Mitraphylline is part of a small family of plant molecules known as spirooxindole alkaloids. These compounds are distinguished by their complex “twisted” ring structures and are recognized for powerful biological effects, including anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory activity.

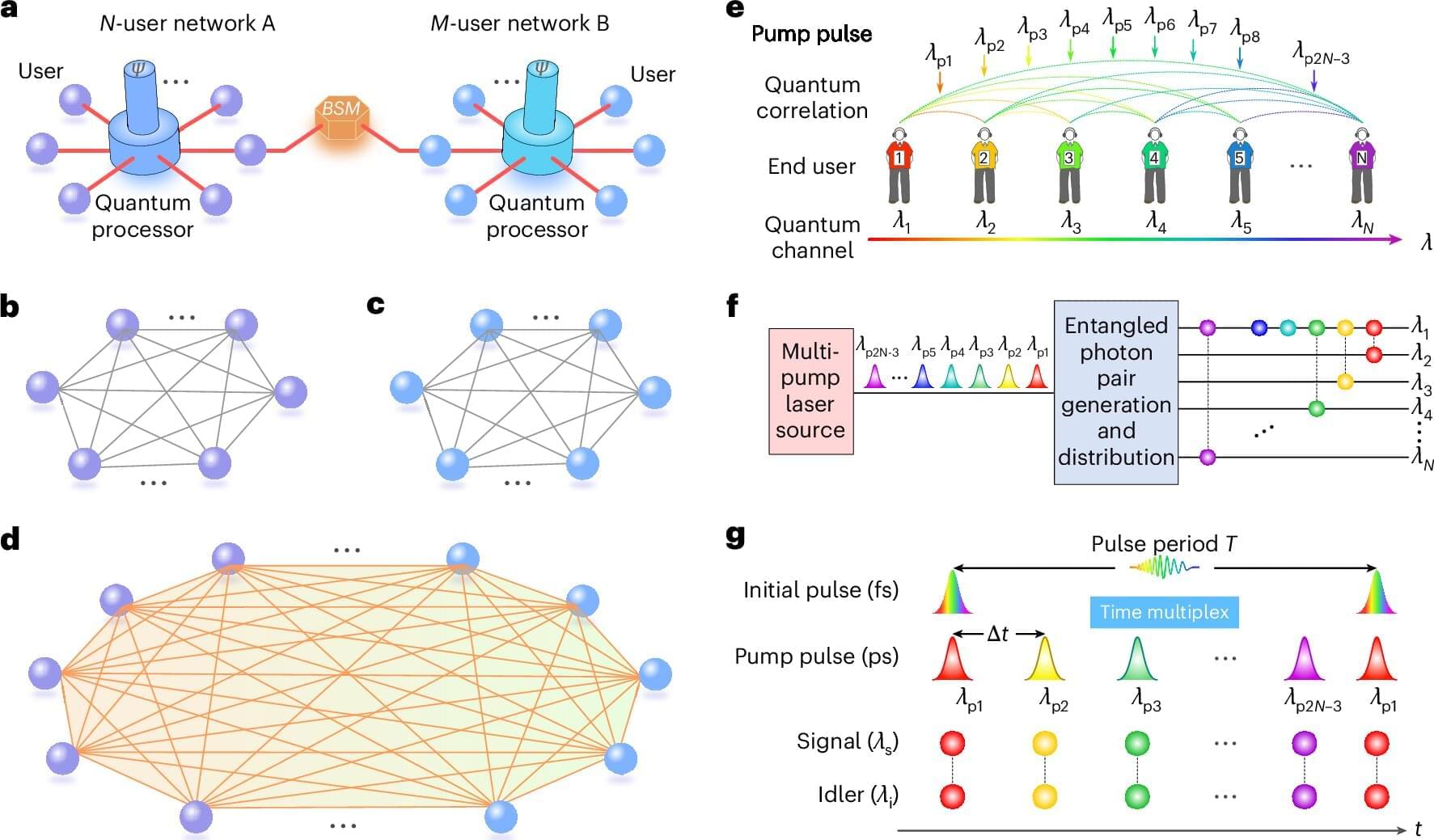

Until recently, researchers did not know the precise molecular process plants use to form spirooxindoles. That mystery began to unravel in 2023 when Dr. Thu-Thuy Dang’s team in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science identified the first plant enzyme capable of twisting a molecule into the distinctive spiro shape.