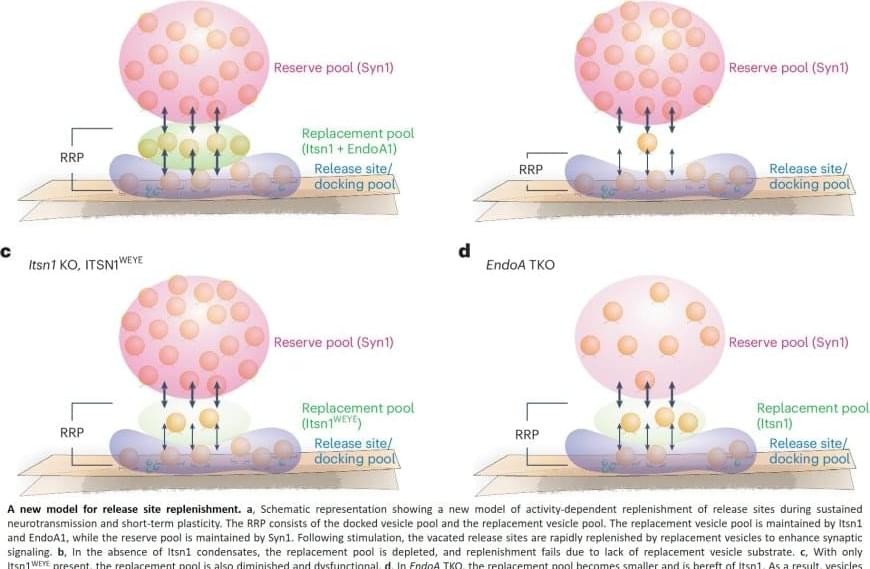

Message transfer from brain cell to brain cell is key to information processing, learning and forming memories. The bubbles, synaptic vesicles, are housed within the synapse — the connection point where brain cells communicate. In typical synapses within the brains of mammals, 300 synaptic vesicles are clustered together in the intersection between any two brain cells, but only a few of these vesicles are used for such message transfer, researchers say. Pinpointing how a synapse knows which vesicles to use has long been a target of research by those who study the biology and chemistry of thought.

In an effort to better understand the operation of these synaptic vesicles, the team designed a study that first focused on endocytosis, a process in which brain cells recycle synaptic vesicles after they are used for neuronal communication.

Already aware of intersectin’s general role in endocytosis and neuronal communication, the scientists genetically engineered mice to lack the gene that codes for intersectin. However, and somewhat to their surprise, the lead says removing the protein did not appear to halt endocytosis in brain cells.

The research team refocused their experiments, taking a closer look at the synaptic vesicles themselves.

Using a high-resolution fluorescence microscope to observe where intersectin is in a synapse, the researchers found it in between vesicles that are used for neuronal communication and those that are not, as if they are physically separating the two.

To further understand the role of intersectin at this location, they used an electron microscope to visualize synaptic vesicles in action across one billionth of a meter. In all the nerve cells from mice lacking this protein, the scientists say synaptic vesicles close to the membrane were absent from the release zone of the synapse, the place where the bubbles would discharge to nearby neurons.

“This suggested that intersectin regulates release, rather than recycling, of these vesicles at this location of the synapse,” says the author.