face_with_colon_three nanomachines could also be used for aging control to prevent aging symptoms.

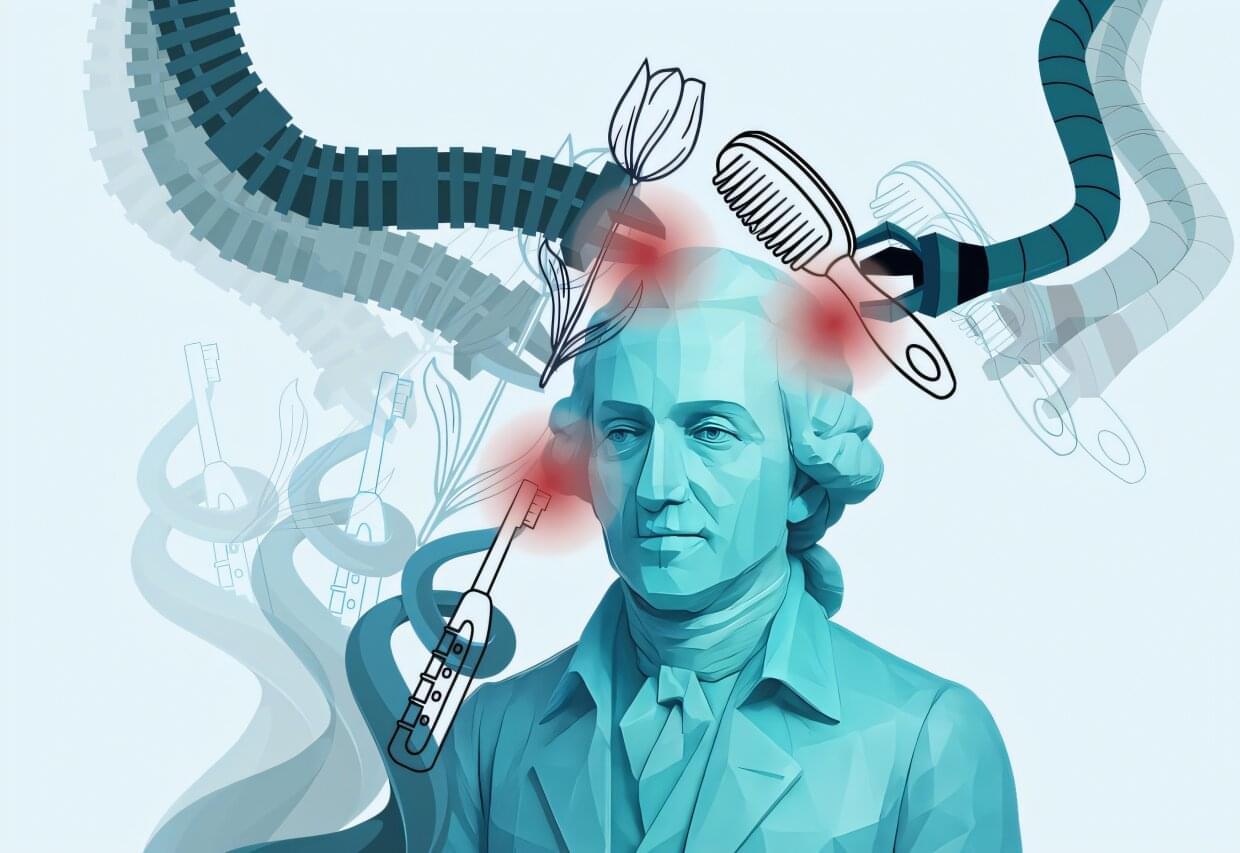

Scientists used a new nanotechnology strategy to reverse Alzheimer’s disease in mice by helping reduce amyloid-beta in the brain by 50–60%.

1 Institut de Neurociències, and.

2Department of Cell Biology, Physiology and Immunology, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Barcelona Spain.

3Institute of Neuroscience, CSIC-UMH, Alicante, Spain.

4Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute-Network Center for Biomedical Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases (CIBERNED), Barcelona, Spain.

The living cell, once thought to be a precise molecular factory, is turning out to be more like an improvising jazz ensemble. The old dogma—one gene, one protein, one function—has collapsed. Molecular biologist Ewa Grzybowska argues that recent discoveries show that proteins can switch folds, shift shapes, or even remain gloriously unstructured, improvising their roles as they go. Genes are not blueprints but texts, open to continuous interpretation by cells. Life, it turns out, is not built like a machine but is instead fluid, improvisational, and brimming with creative possibility.

1. The old paradigms in biology

When Watson and Crick decoded DNA in 1953 and the mechanism of protein-making was discovered, we obtained an extraordinary tool to explain the inner workings of life. The basic principle of making one protein from one DNA template (gene) with the assistance of one messenger RNA (mRNA) and several well-defined amino-acid-transporting RNAs (tRNAs) was so successful that it has been enshrined in millions of textbooks and not questioned for a long time.

High levels of calcium are toxic to cells and contribute to loss of neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. A new study published in JCI Insight identifies a mechanism through which the young brain protects itself against high calcium levels, and it could help scientists learn how to protect the brain from this devastating neurodegenerative condition.

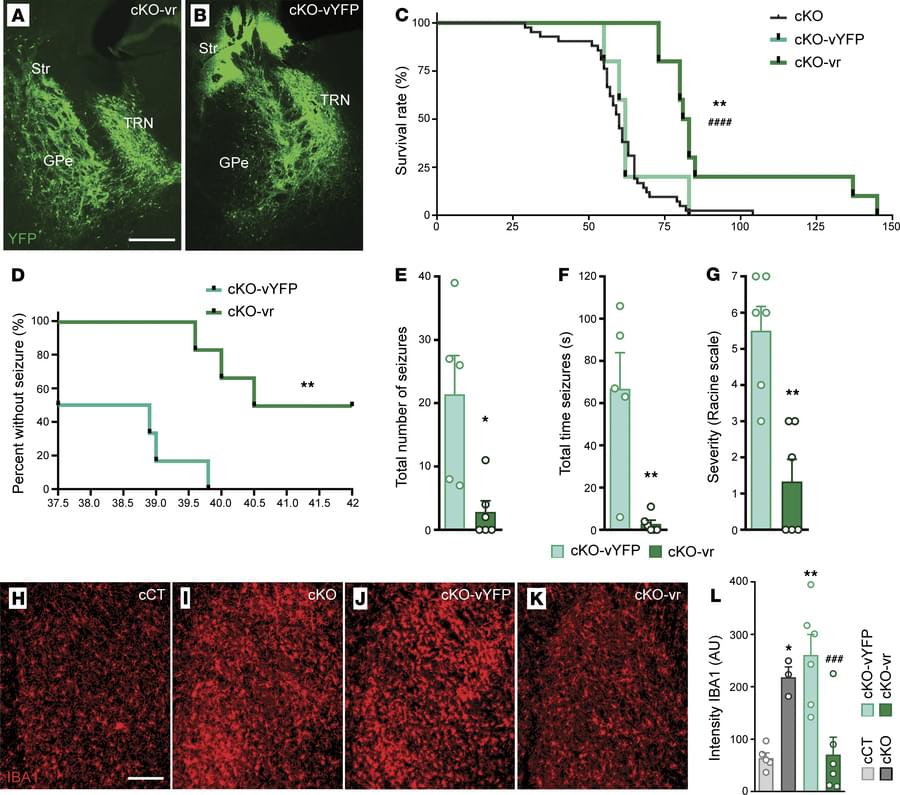

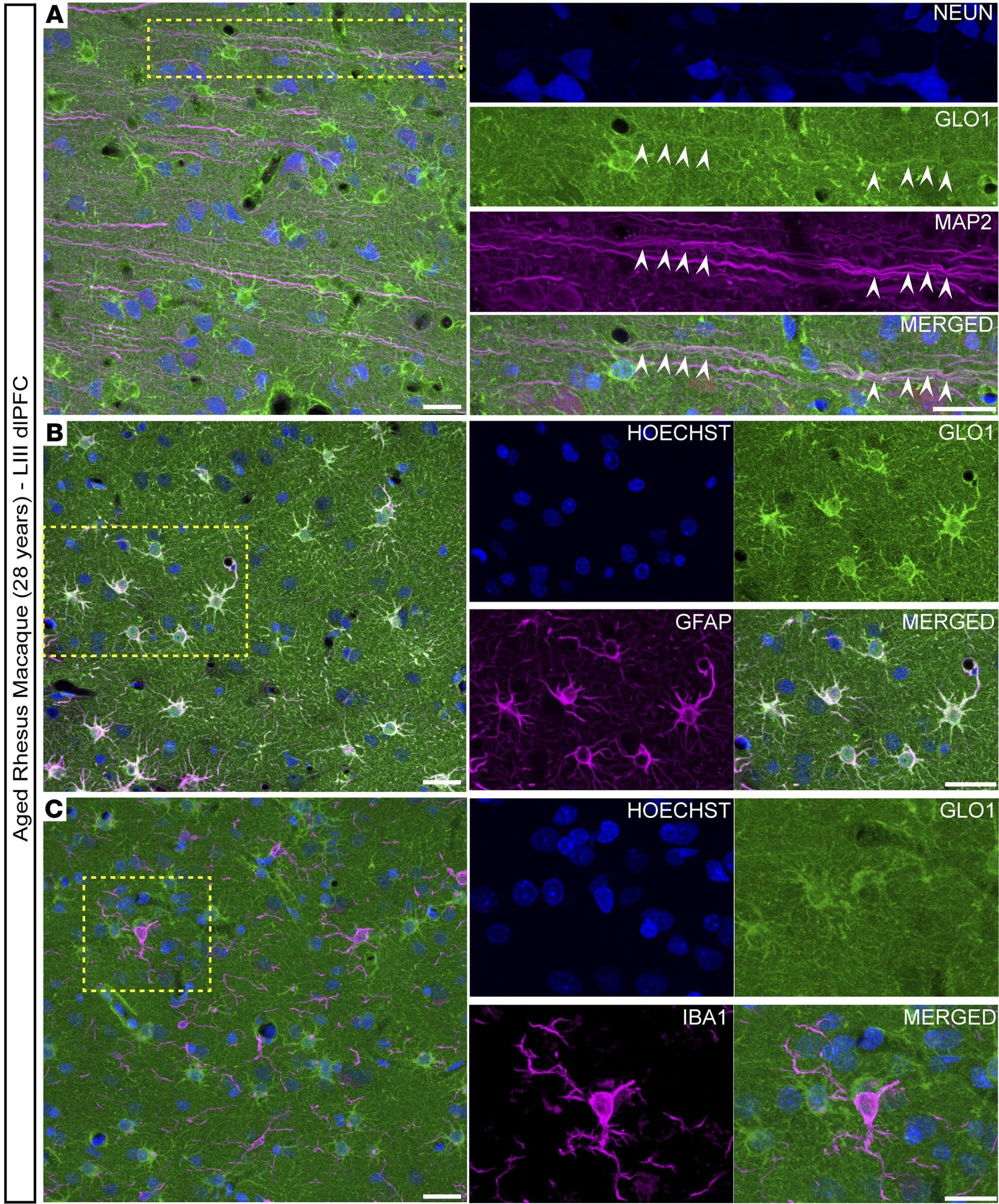

Glyoxalase 1 (GLO1) is a protein that plays an essential role in getting rid of toxic byproducts in cells. In the study, Yale School of Medicine (YSM) researchers discovered elevated GLO1 levels in the brains of animals with excessive levels of cellular calcium, finding that the brain increased GLO1 expression as a protective mechanism to mitigate the effects of the calcium dysregulation.

However, with advancing age, GLO1 activity declined, the researchers found, which may make the brain less resilient to neurodegeneration. The study could inform the development of therapeutics that target GLO1 and prevent neurodegeneration.

More than 1 million Americans live with tremors, slowed movement and speech changes caused by Parkinson’s disease—a degenerative and currently incurable condition, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation and the Mayo Clinic. Beyond the emotional toll on patients and families, the disease also exerts a heavy financial burden. In California alone, researchers estimate that Parkinson’s costs the state more than 6 billion dollars in health care expenses and lost productivity.

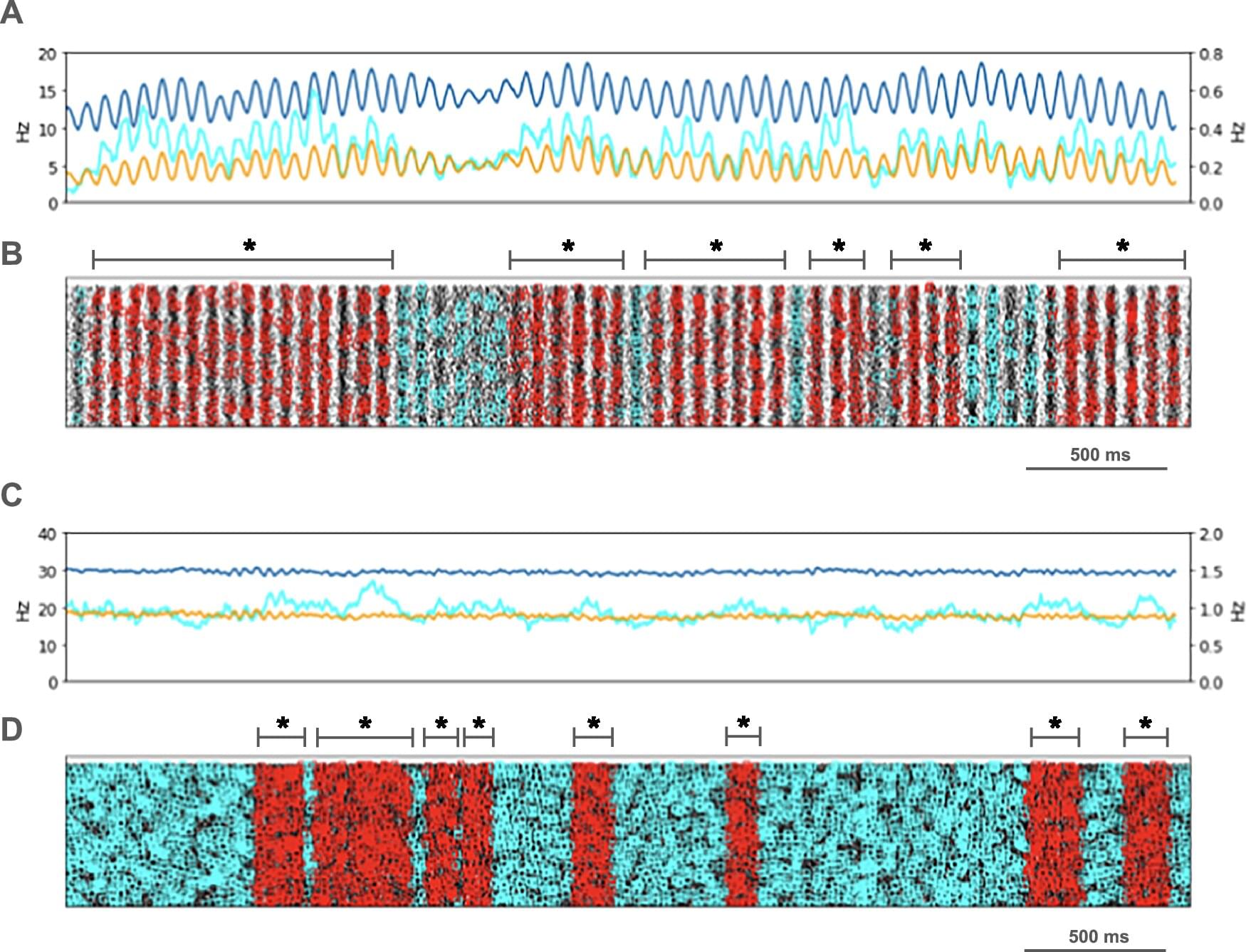

Scientists have long sought to understand the deeper brain mechanisms driving Parkinson’s symptoms. One long-standing puzzle involved an unusual surge of brain activity known as beta waves—electrical oscillations around 15 Hertz observed in patients’ motor control centers. Now, thanks to supercomputing resources provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation’s ACCESS program, researchers may have finally discovered what causes these waves to spike.

Using ACCESS allocations on the Expanse system at the San Diego Supercomputer Center—part of UC San Diego’s new School of Computing, Information, and Data Sciences—researchers with the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) Collaborative Research Network modeled how specific brain cells malfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Their findings could pave the way for more targeted treatments.

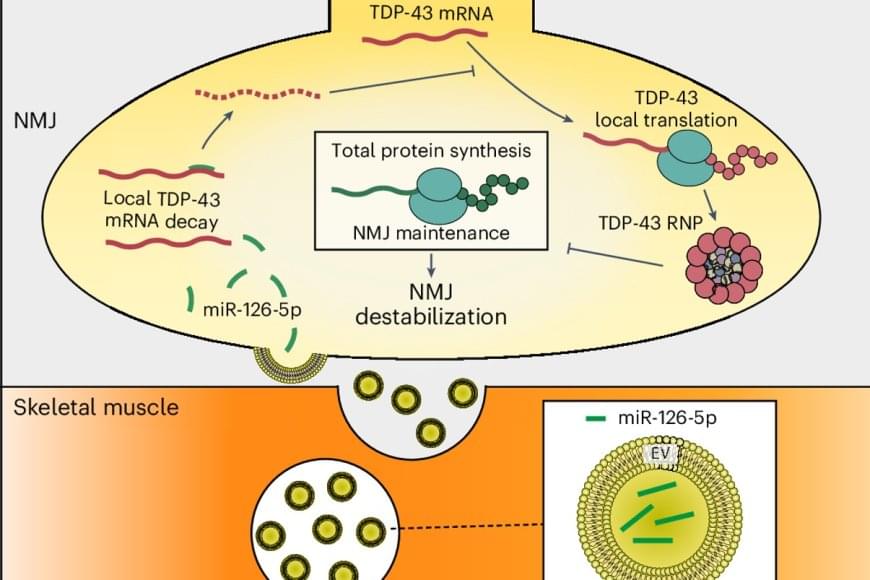

The current study was based on a feature of ALS discovered previously in the lab: toxic clusters (aggregates) of a protein called TDP-43 (usually responsible for regulating protein production at the site) form at the tip of the nerve, where it meets the muscle. To discover how these TDP-43 aggregates are formed, the researchers used a mouse model for ALS, tissues from ALS patients, and cultures of human stem cells.

The study found that muscle cells produce small RNA molecules called microRNA-126 and send them in vesicles, through the synapsis, to the tip of the nerve cell. The role of these molecules is to prevent the expression of the TDP-43 protein at the neuromuscular junction when it is not needed.

The author explains: “We discovered that in ALS, the muscle produces a smaller amount of microRNA-126, which leads to an excess of TDP-43. The excess protein forms toxic aggregates that attack molecules essential for functioning of the mitochondria — the nerve cell’s powerhouse. Damage to the mitochondria causes an energy deficit, gradually destroying motor neurons and leaving patients’ muscles paralyzed.”

The study further showed that when the amount of microRNA-126 is reduced, a process similar to ALS occurs, and the neurons are destroyed. Conversely, increasing the level of microRNA-126 in tissues taken from ALS patients and in ALS model mice led to a decrease in the levels of TDP-43, and the neurons stopped degenerating and even regenerated.

The researchers concluded that adding microRNA-126 rescues neurons damaged by ALS, prevents degeneration of the neuromuscular junction, and could serve as a basis for developing effective drugs for this currently incurable disease.

Researchers in this study opened a new avenue for treating the fatal degenerative disease ALS, considered incurable until now. The researchers identified a new molecular mechanism that plays a key role in the disease and were able to neutralize it through gene therapy.

“We have a much better appreciation for how those subtle structural changes can significantly increase the synthetic challenge,” says Mohammad Movassaghi, an MIT professor of chemistry. “Now we have the technology where we can not only access them for the first time, more than 50 years after they were isolated, but also we can make many designed variants, which can enable further detailed studies.”

In tests in human cancer cells, a derivative of verticillin A showed particular promise against a type of pediatric brain cancer called diffuse midline glioma. More tests will be needed to evaluate its potential for clinical use, the researchers say.

The study involving 1,119 participants will be published in Cell Reports Medicine.

Currently, genetic testing is divided into three distinct approaches:

In a new study, scientists have developed a more precise genetic risk score to determine whether a person is likely to develop arrhythmia, an irregular heartbeat that can lead to serious conditions such as atrial fibrillation (AFib) or sudden cardiac death.

Their approach not only improves the accuracy of heart disease risk prediction but also offers a comprehensive framework for genetic testing that, according to the scientists, could be applied to anything, including other complex, genetically influenced diseases like cancer, Parkinson’s Disease and autism.

“It’s a very cool approach in which we are combining rare gene variants with common gene variants and then adding in non-coding genome information. To our knowledge, no one has used this comprehensive approach before, so it’s really a roadmap of how to do that,” said co-corresponding author.

Imagine having a continuum soft robotic arm bend around a bunch of grapes or broccoli, adjusting its grip in real time as it lifts the object. Unlike traditional rigid robots that generally aim to avoid contact with the environment as much as possible and stay far away from humans for safety reasons, this arm senses subtle forces, stretching and flexing in ways that mimic more of the compliance of a human hand. Its every motion is calculated to avoid excessive force while achieving the task efficiently.

In the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and Laboratory for Information and Decisions Systems (LIDS) labs, these seemingly simple movements are the culmination of complex mathematics, careful engineering, and a vision for robots that can safely interact with humans and delicate objects.

Soft robots, with their deformable bodies, promise a future where machines move more seamlessly alongside people, assist in caregiving, or handle delicate items in industrial settings. Yet that very flexibility makes them difficult to control. Small bends or twists can produce unpredictable forces, raising the risk of damage or injury. This motivates the need for safe control strategies for soft robots.