A study led by a physician-scientist at the University of Arizona College of Medicine–Tucson’s Sarver Heart Center identified a drug candidate that appears to reverse the progression of a type of heart failure in mouse models, which could lead to expanded treatment options for humans. The results are published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Heart failure occurs when the heart doesn’t pump blood properly. In about half of cases, the muscle is weak and has difficulty pumping. The rest result from a stiff muscle, a type called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, or HFpEF.

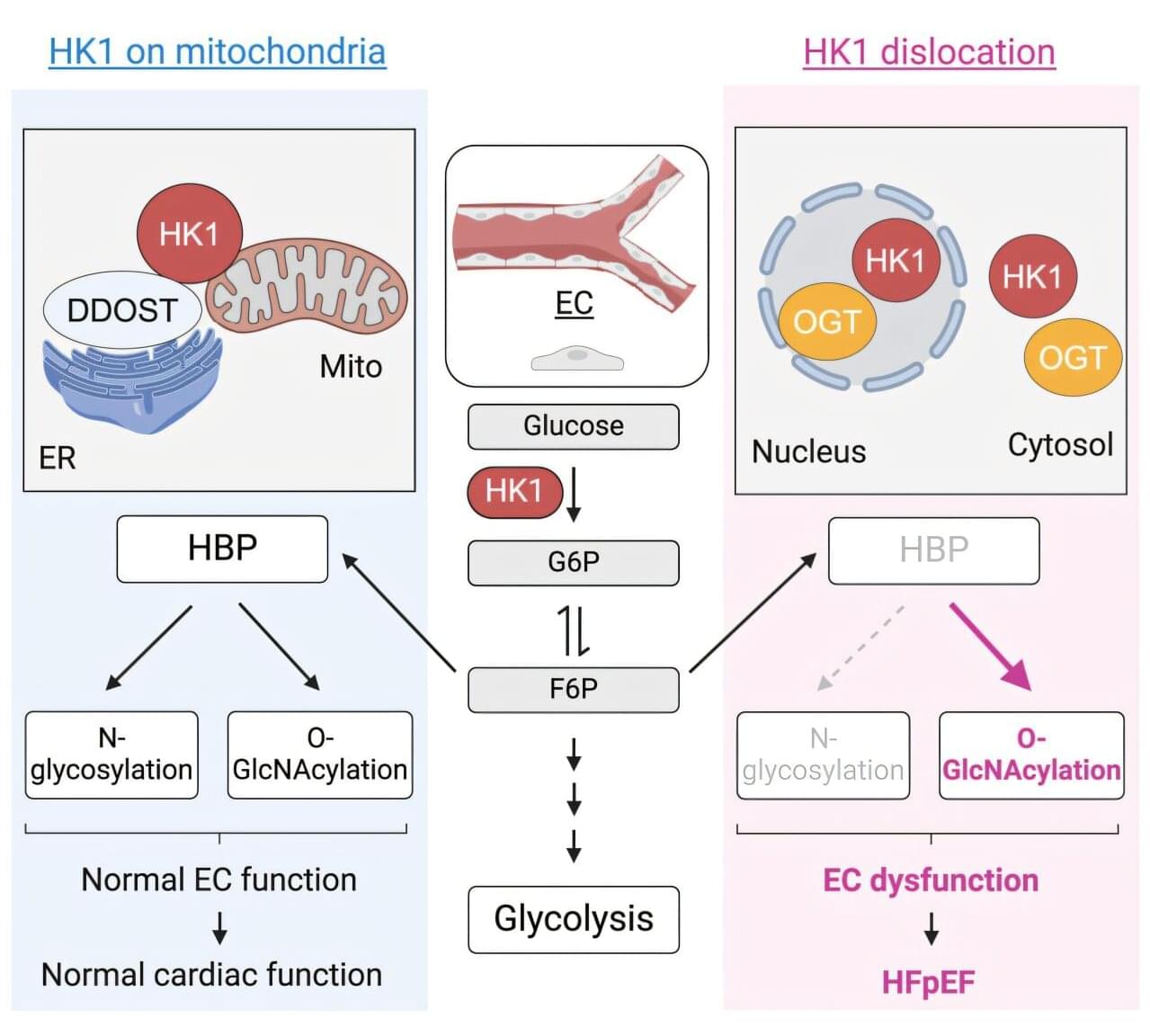

The research team found that a key ingredient in triggering heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is an enzyme that escapes into an area of the cell where it’s not normally found. Once there, it reacts with another enzyme to convert glucose, a type of sugar, into harmful byproducts that set off a chain reaction, ultimately reducing the heart’s elasticity.