As anyone who uses the internet will know, the way we find information has fundamentally changed. For the last three decades, search engines have delivered ranked lists of links in response to our queries, and it was our job to search through them to find what we wanted. Now, major search engines use generative AI tools to deliver a single coherent answer, often embedded with a few links. But how does this approach compare with the traditional method? In a comprehensive new study, scientists compared these two approaches to see what we are gaining and losing.

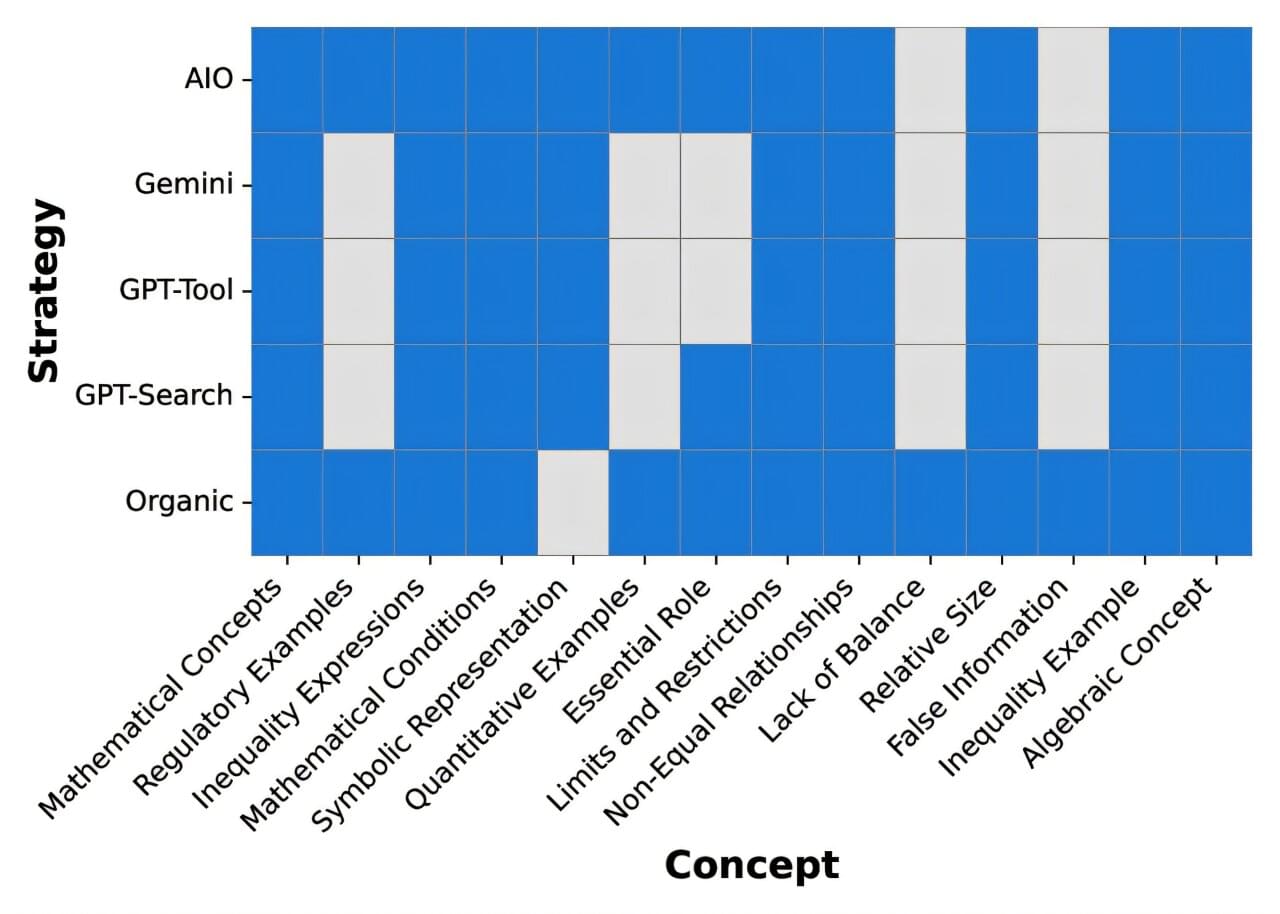

To figure this out, researchers from Ruhr University Bochum and the Max Planck Institute for Software Systems compared traditional Google Search with four generative search engines: Google AI Overview (AIO), Gemini, GPT-4o-Search and GPT-4o with Search Tool. The team ran thousands of queries covering six main areas, including general knowledge, politics, science and shopping.

Then they made a detailed comparison of the two search styles based on three key metrics. First, they analyzed source diversity by checking the websites AI used against traditional search’s top links. Second, they measured knowledge reliance to see how much AI relied on its own internal memory rather than searching the web for fresh information.