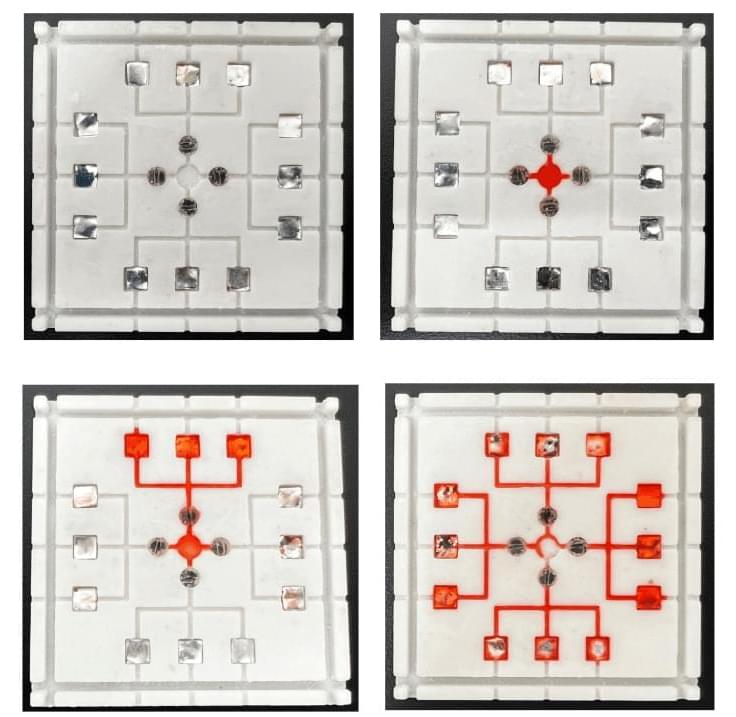

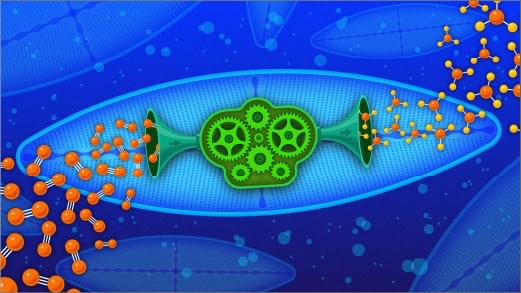

Chip design can rapidly and efficiently test for multiple pathogens simultaneously, potentially reducing foodborne illness. Researchers have developed a new method for detecting foodborne pathogens that is faster, cheaper, and more effective than existing methods. Their microfluidic chip uses light to detect multiple types of pathogens simultaneously and is created using 3D printing, making it easy to fabricate in large amounts and modify to target specific pathogens. The researchers hope their technique can improve screening processes and keep contaminated food out of the hands of consumers.

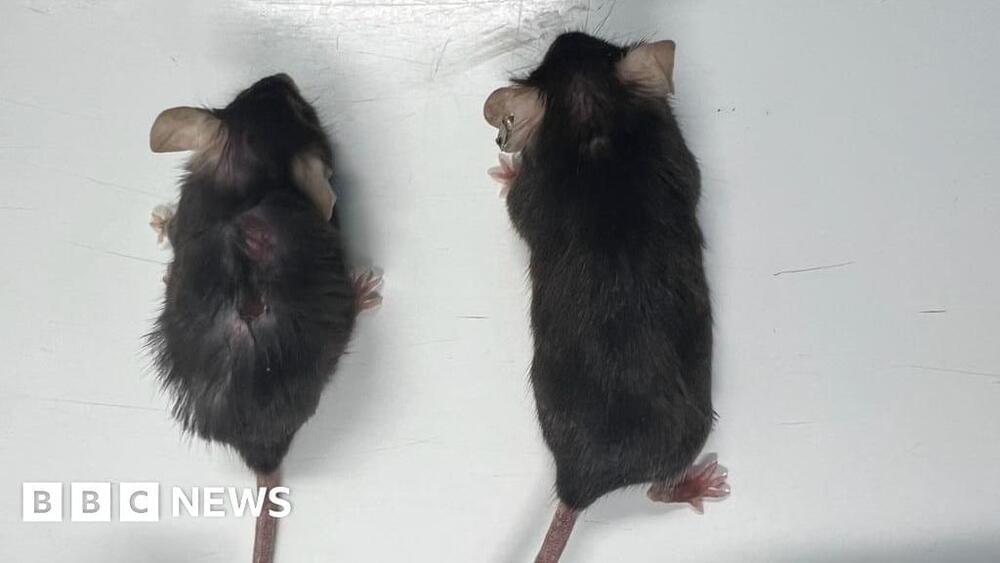

Every so often, a food product is recalled because of some sort of contamination. For consumers of such products, a recall can trigger doubt in the safety and reliability of what they eat and drink. In many cases, a recall will come too late to keep some people from getting ill.

In spite of the food industry’s efforts to fight pathogens, products are still contaminated and people still get sick. Much of the problem stems from the tools available to screen for harmful pathogens, which are often not effective enough at protecting the public.