NVIDIA today announced the general availability of NVIDIA ACE generative AI microservices to accelerate the next wave of digital humans, as well as new generative AI breakthroughs coming soon to the platform.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Boeing, NASA target June 5 for Starliner’s debut crew flight

Boeing and NASA said on Sunday that their teams are preparing to launch the new Starliner space capsule on June 5 after scrubbing its inaugural test flight launch attempt on Saturday.

The Starliner capsule had stood ready for blast-off from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Saturday before a ground system computer triggered an automatic abort command that shut down the launch sequence.

NASA said its teams worked overnight to assess the ground support equipment at the launch pad that encountered issues during the countdown and identified an issue with a ground power supply within one of the chassis which provides power to a subset of computer cards controlling various system functions.

Nvidia unveils next-gen AI chip platform Rubin, set for 2026 release

Nvidia Corp. has launched Rubin, its next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) chip platform, which will be available in 2026, according to CEO Jensen Huang. The announcement was made during a presentation at National Taiwan University in Taipei as part of the Computex trade fair.

Rubin platform to include advanced CPUs, GPUs, and networking chips.

The Rubin chip family will include new GPUs, CPUs, and networking processors. The new CPU, called Versa, will be geared to improve AI capabilities. The GPUs, which are critical for powering AI applications, will use next-generation high-bandwidth memory from industry giants including SK Hynix, Micron, and Samsung. Despite the enthusiasm surrounding the introduction, Huang revealed only limited information regarding the Rubin platform’s specific features and capabilities.

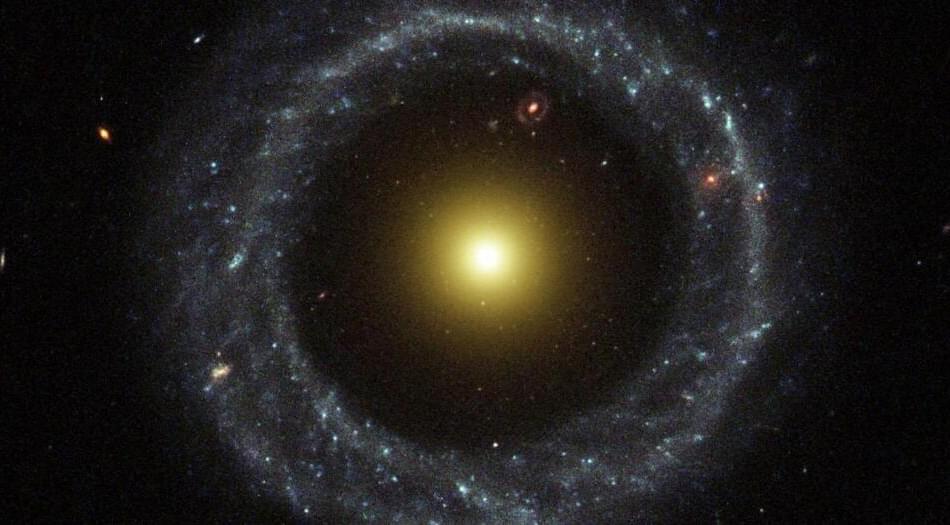

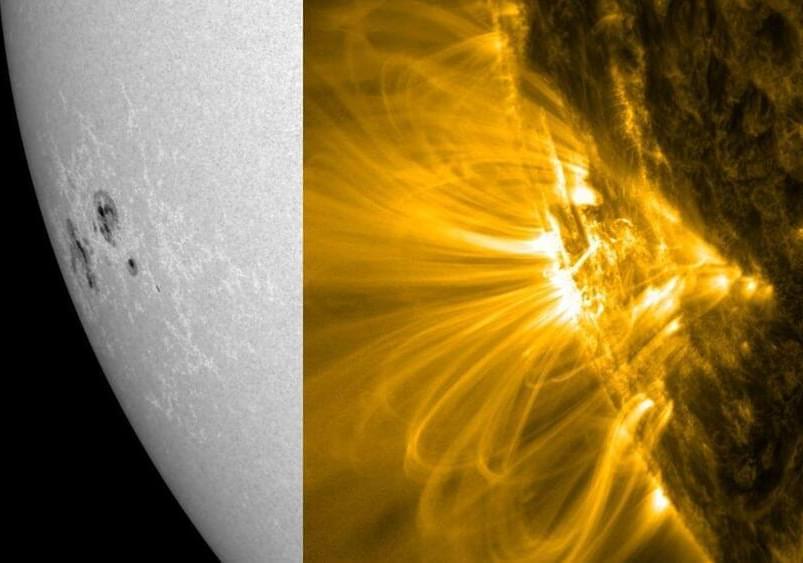

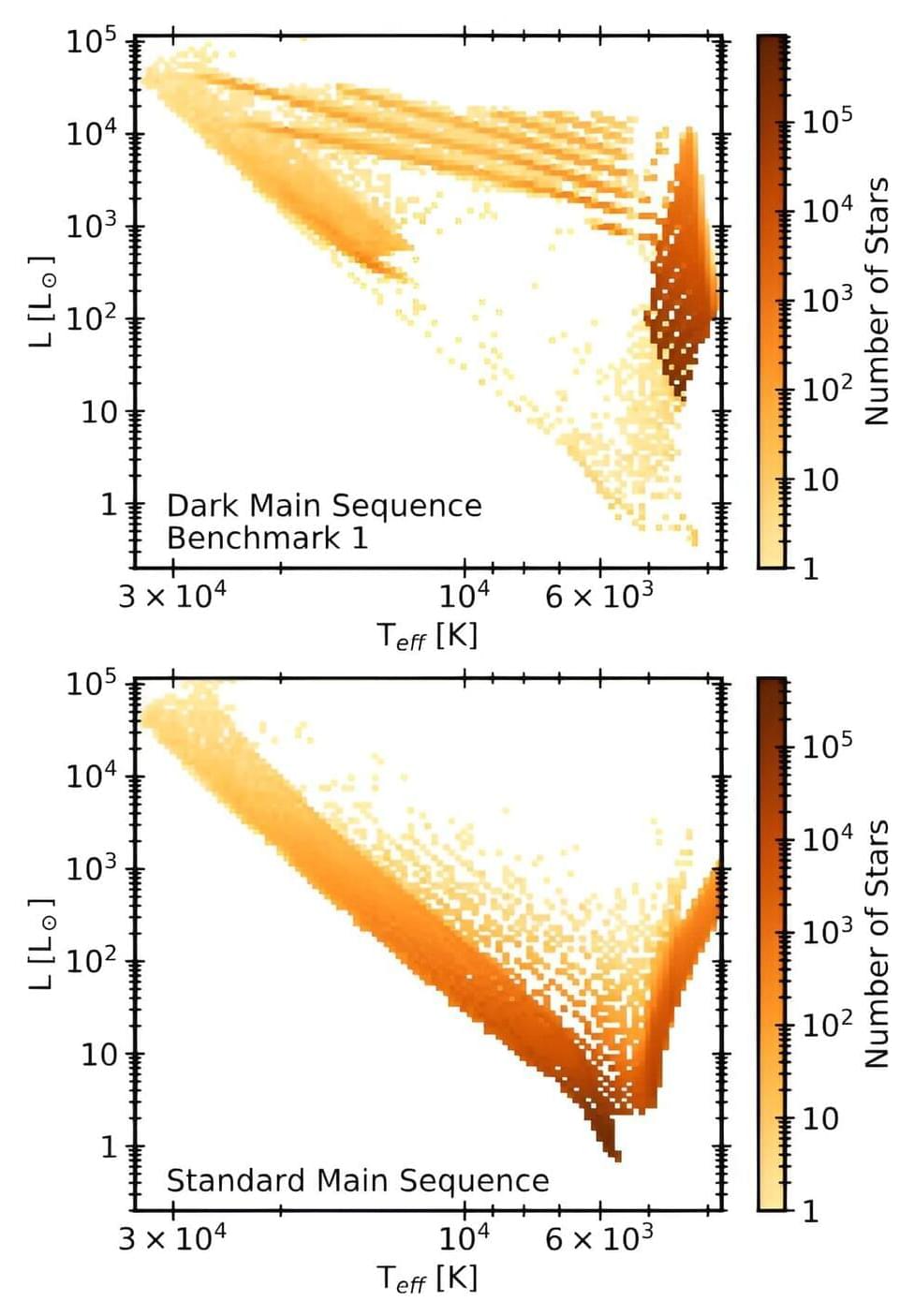

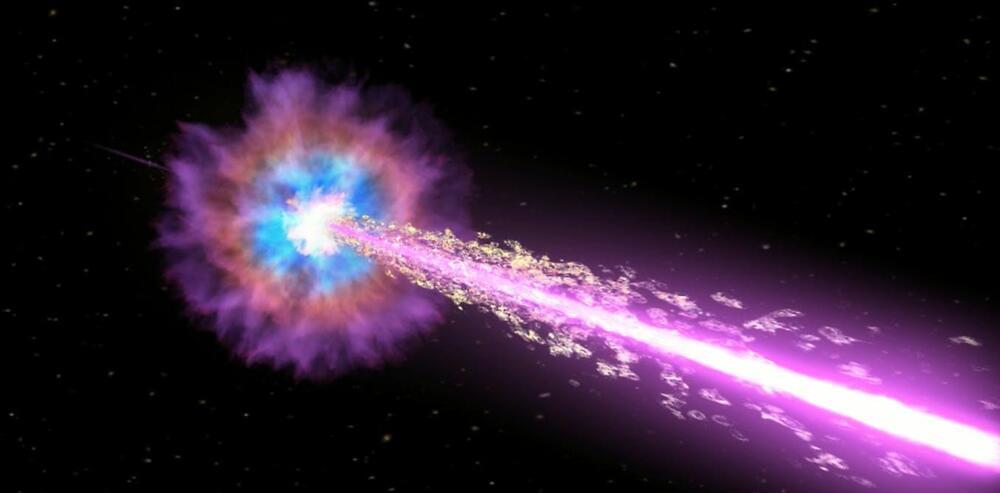

Dark matter could make our galaxy’s innermost stars immortal

They calculated stellar populations without and with the presence of dark matter. With dark matter, more massive stars experienced a lower dark matter density, and hydrogen in their core fused more slowly and their evolution was slowed down. But stars in a higher dark matter density region were changed significantly—they maintained equilibrium through dark matter burning with less fusion or no fusion, which led to a new stellar population in an HR region above the main sequence.

“Our simulations show that stars can survive on dark matter as a fuel alone,” said lead co-author Isabelle John from Stockholm University, “and because there is an extremely large amount of dark matter near the Galactic Center, these stars become immortal,” staying forever young, occupying a new, distinct, observable region of the HR diagram.

Their dark matter model may be able to explain more of the known mysteries. “For lighter stars, we see in our simulations that they become very puffy and might even lose parts of their outer layers,” said John. She noted that “something similar to this might be observed at the Galactic Center: the so-called G-objects, which might be star-like, but with a gas cloud around them.”

Hackers Targeting 1,500 Banks and Their Customers in Push To Drain Accounts Across 60 Countries: Report

Black hat hackers have reportedly unleashed malicious software targeting over 1,500 banks and their customers worldwide.

Security researchers at IBM say a revamped version of the Grandoreiro banking trojan has just rolled out, enabling attackers to perform banking fraud in 60 countries.

The malware allows attackers to send email notices that appear to be urgent government requests for payments.