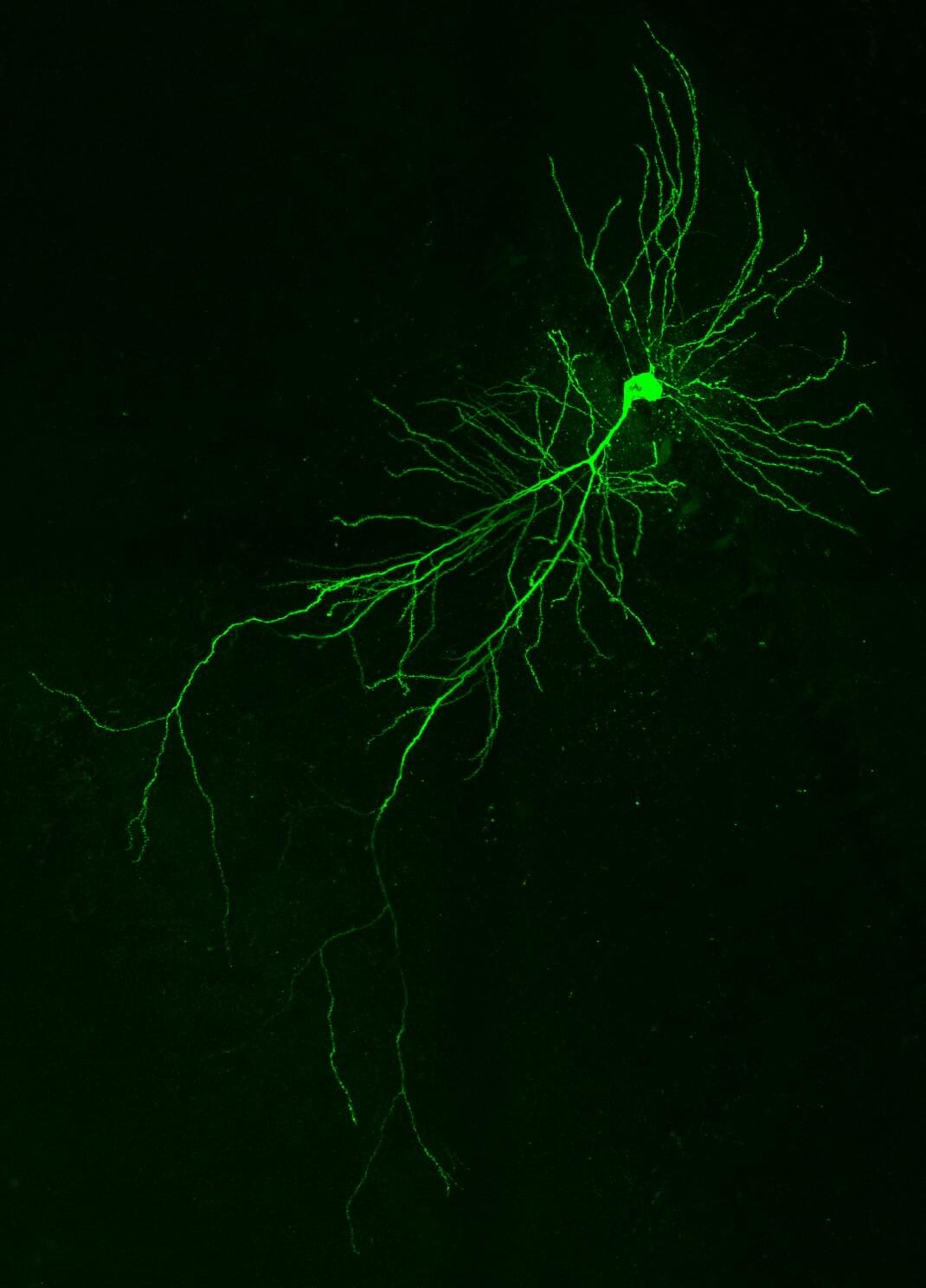

Cells have a trick called splicing. They can cut a gene’s message into pieces and decide which fragments to keep. By mixing and matching these fragments, a single gene can produce many different proteins, giving tissues and organs more options to thrive and evolve. Out of all tissues, splicing is most prevalent in the brain.

Researchers at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) have discovered that one such fragment, a “microexon” just nine amino acids long, is inserted into the DAAM1 protein exclusively in neurons and nowhere else in the body. The inclusion of the microexon is critical for healthy neuronal development, with effects rippling all the way up to memory function. The findings are published in Nature Communications.

DAAM1 makes a protein that helps cells maintain their shape and enables their movement. When the team deleted the nine-letter microexon in mice, the animals were healthy at birth, but their adult brain cells had half of the usual “learning spines,” protrusions known to be important for learning and retrieval of memories.