The galaxy’s stars keep a record of its history. By reading those stories, astronomers are learning more about how the Milky Way came to be—and about the galaxy we live in today.

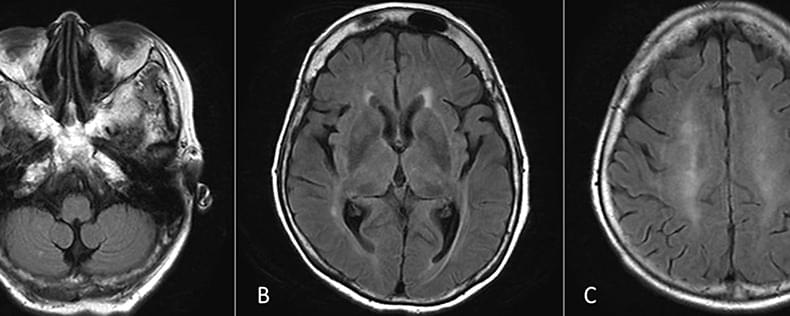

Nephrologists — know the CTRX encephalopathy risk in ESRD patients. This case of a hemodialysis patient found blood and CSF concentrations 10 times usual — dose adjustment may be needed. Monitor for neuro changes when using CTRX in renal failure. pharmacology.

Ceftriaxone (CTRX) does not require dose adjustment based on the renal function status and is used to treat infections. Recently, several studies reported the incidence of antibiotic-associated encephalopathy due to CTRX in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). We experienced a case of CTRX-related encephalopathy in a patient on hemodialysis. When CTRX-related encephalopathy was discovered, the CTRX concentrations were measured in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The highest blood and CSF CTRX concentrations in this patient were 967 and 100.7 μg/mL, respectively, which were approximately 10 times higher than the CSF concentrations in a previously evaluated patient with CTRX encephalopathy. The concentration of CTRX may be increased in patients with ESRD. Hence, encephalopathy must be suspected in this patient group when CTRX is used.

The wait time for a heart transplant is long — from many months to over a year. Some patients will never get the transplant they need.

But researchers may have come up with an artificial heart solution: a titanium, pumpless, device with spinning magnets — and it looks nothing like a bonafide heart.

The problem: Heart failure affects over six million people every year in the U.S., and treatment options are slim. Medication can help, but some people need a heart transplant for a full recovery. Still, donor hearts are hard to come by. The number of people who need a heart far exceeds what’s available. And, donor hearts aren’t one-size-fits-all. The blood type and size need to be just right.

The Earth spins at different rates depending where you are on the globe. If it started to spin faster, you’d eventually be too dead to worry about it.

Scientists are trying to figure out if time travel is even theoretically possible. If it is, it looks like it would take a whole lot more knowledge and resources than humans have now to do it.

Immigration to and living on Mars have long been depicted in science fiction. But before that dream turns into reality, there is a hurdle humans have to overcome—the lack of chemicals such as oxygen essential for long-term survival on the planet. However, the recent discovery of water activity on Mars is promising.

Scientists are now exploring the possibility of decomposing water to produce oxygen through electrochemical water oxidation driven by solar power with the help of oxygen evolution reaction (OER) catalysts. The challenge is to find a way to synthesize these catalysts in situ using materials on Mars, instead of transporting them from the Earth, which is costly.

To tackle this problem, a team led by Prof. Luo Yi, Prof. Jiang Jun, and Prof. Shang Weiwei from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), recently made it possible to synthesize and optimize OER catalysts automatically from Martian meteorites with their robotic artificial intelligence (AI)-chemist.

Having healthy mitochondria, the organelles that produce energy in all our cells, usually portends a long healthy life whether in humans or in C. elegans, a tiny, short-lived nematode worm often used to study the aging process.

Researchers at the Buck Institute have identified a new drug-like molecule that keeps mitochondria healthy via mitophagy, a process that removes and recycles damaged mitochondria in multicellular organisms. The compound, dubbed MIC, is a natural compound that extended lifespan in C. elegans, ameliorated pathology in neurodegenerative disease models of C. elegans, and improved mitochondrial function in mouse muscle cells. Results are published in the November 13, 2023, edition of Nature Aging.

Defective mitophagy is implicated in many age-related diseases. It’s tied to neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s; it plays a role in cardiovascular diseases including heart failure; it influences metabolic disorders including obesity and type 2 diabetes; it is implicated in muscle wasting and sarcopenia and has a complex relationship with cancer progression.

As information and communication technologies (ICT) process data, they convert electricity into heat. Already today, the global ICT ecosystem’s CO2 footprint rivals that of aviation. It turns out, however, that a big part of the energy consumed by computer processors doesn’t go into performing calculations. Instead, the bulk of the energy used to process data is spent shuttling bytes between the memory to the processor.

In a paper published in the journal Nature Electronics, researchers from EPFL’s School of Engineering in the Laboratory of Nanoscale Electronics and Structures (LANES) present a new processor that tackles this inefficiency by integrating data processing and storage onto a single device, a so-called in-memory processor.

They broke new ground by creating the first in-memory processor based on a two-dimensional semiconductor material to comprise more than 1,000 transistors, a key milestone on the path to industrial production.

If you have any form of Arachnophobia, do not read this article. You’ve been warned. Now if you’re like me and have a mad respect for Mother Nature, I posit you this query. Did you know that spiders can fly? And not by the way you may think.

Good news for your nightmares: Spiders can fly. Despite not having wings, new research shows that spiders have the ability to propel themselves using the Earth’s electric field, with little to no help from wind or webs. Because humans can’t feel these electric currents, their role in biology can often go ignored. But if electrostatic is what is helping spiders fly more than two miles high in the air, let’s pay attention.

In a study published in Current Biology on Thursday, Drs. Erica L. Morley and Daniel Robert of the University of Bristol found that when spiders are placed in a chamber with no wind but a small electric field, they were still able to to fly, despite the prevailing idea that a spider’s flight was reliant on wind currents.

When spiders are airborne, a behavior that’s often described as “ballooning,” most observers assumed that their movement is influenced by air streams. However, this prevailing view couldn’t explain why larger spiders are airborne for extended periods of time, nor could any current aerodynamic models explain these vague ballooning mechanisms.