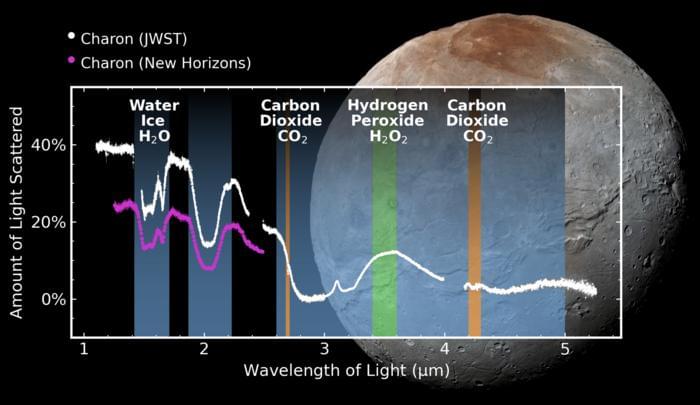

What secrets can Pluto’s moon, Charon, reveal about the formation and evolution of planetary bodies throughout the solar system? This is what a recent study published in Nature Communications hopes to address as an international team of researchers led by the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to conduct the first-time detection of hydrogen peroxide and carbon dioxide on Charon’s surface, which adds further intrigue to this mysterious moon, along with complementing previous discoveries of water ice, ammonia-bearing species, and organic materials, the last of which scientists hypothesize could explain Charon’s gray and red surface colors.

“The advanced observational capabilities of Webb enabled our team to explore the light scattered from Charon’s surface at longer wavelengths than what was previously possible, expanding our understanding of the complexity of this fascinating object,” said Dr. Ian Wong, who is a staff scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute and a co-author on the study.

Detecting hydrogen peroxide is significant since it forms from the broken-up oxygen and hydrogen atoms after water ice is exposed to cosmic rays, solar wind, or solar ultraviolet light. This indicates that the Sun’s activity influences surface processes so far away, with Charon being approximately 3.7 billion miles from the Sun. The researchers determined that Charon’s carbon dioxide serves as a light coating on Charon’s water-ice heavy surface. While the surface of Charon was studied in-depth from NASA’s New Horizons mission in 2015, these new findings provide greater understanding of the physics-based processes responsible for Charon’s unique surface features.