Patients with spinal cord injuries have been offered the chance to walk again after the success of a Chinese trial.

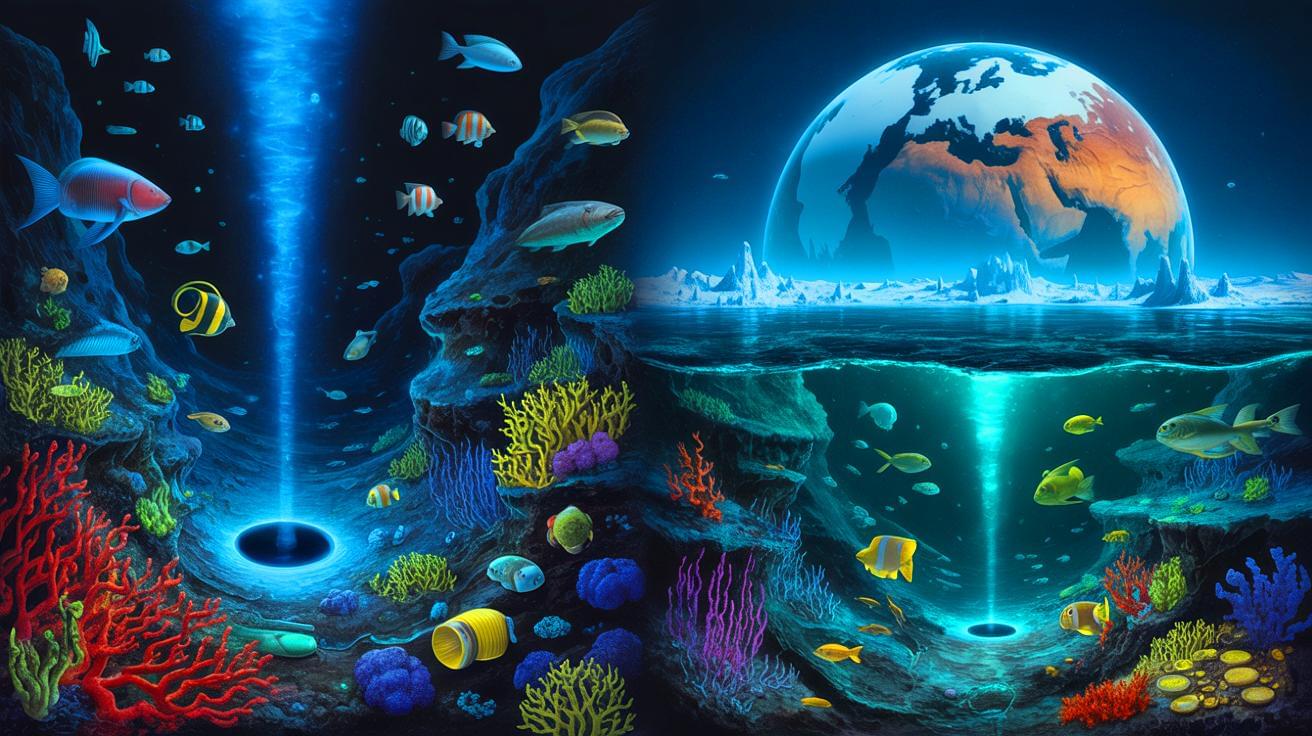

IN A NUTSHELL 🌊 Scientists are studying Earth’s deep-sea hydrothermal vents as a model for potential life on Europa. 🔬 James Holden’s team uses lab simulations to understand how microbes survive in extreme conditions. 🚀 The Europa Clipper mission aims to explore Europa’s ice shell and subsurface ocean, searching for signs of life. 🌌 Discoveries

A robot trained on videos of surgeries performed a lengthy phase of a gallbladder removal without human help. The robot operated for the first time on a lifelike patient, and during the operation, responded to and learned from voice commands from the team—like a novice surgeon working with a mentor.

The robot performed unflappably across trials and with the expertise of a skilled human surgeon, even during unexpected scenarios typical in real-life medical emergencies.

The work, led by Johns Hopkins University researchers, is a transformative advancement in surgical robotics, where robots can perform with both mechanical precision and human-like adaptability and understanding.

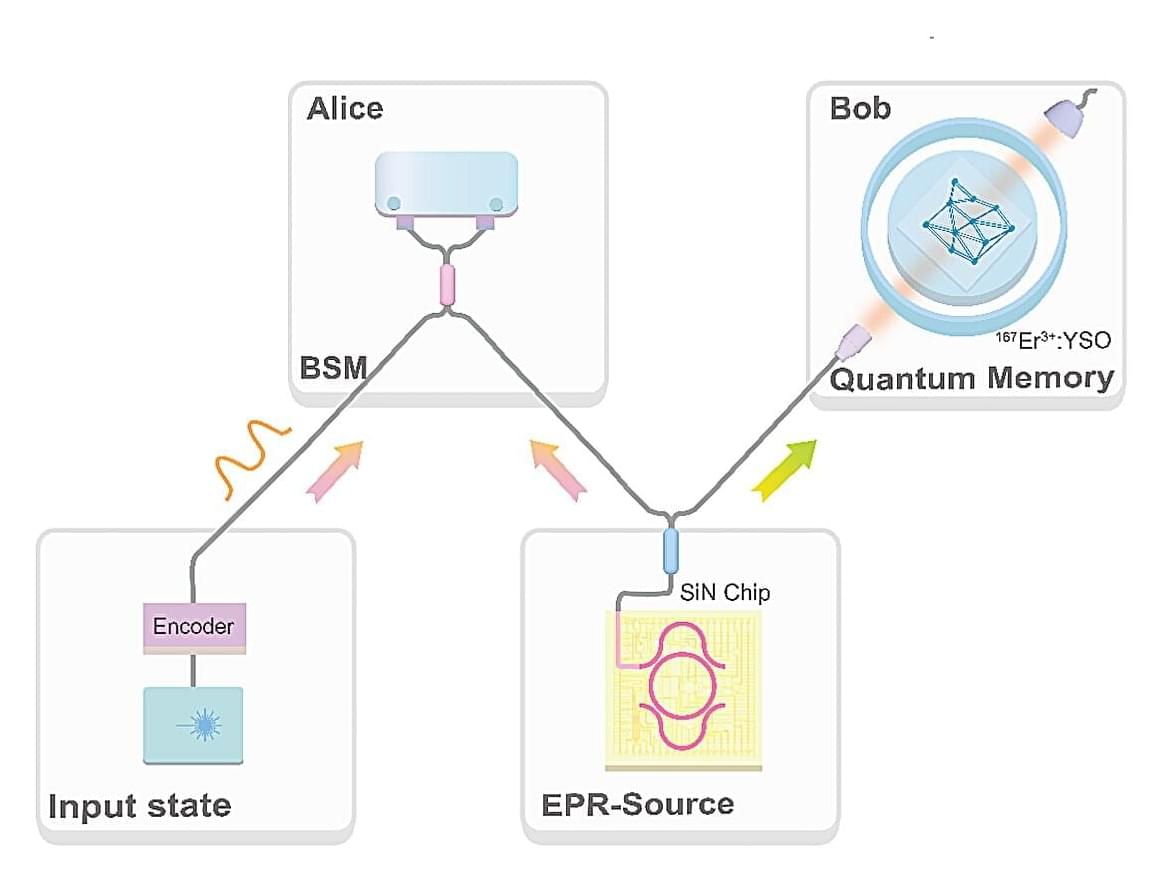

Quantum teleportation is a fascinating process that involves transferring a particle’s quantum state to another distant location, without moving or detecting the particle itself. This process could be central to the realization of a so-called “quantum internet,” a version of the internet that enables the safe and instant transmission of quantum information between devices within the same network.

Quantum teleportation is far from a recent idea, as it was experimentally realized several times in the past. Nonetheless, most previous demonstrations utilized frequency conversion rather than natively operating in the telecom band.

Researchers at Nanjing University recently demonstrated the teleportation of a telecom-wavelength photonic qubit (i.e., a quantum bit encoded in light at the same wavelengths supporting current communications) to a telecom quantum memory. Their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, could open new possibilities for the realization of scalable quantum networks and thus potentially a quantum internet.