As commercial interest in quantum technologies accelerates, entrepreneurial minds at the University of Waterloo are not waiting for opportunities—they are creating them.

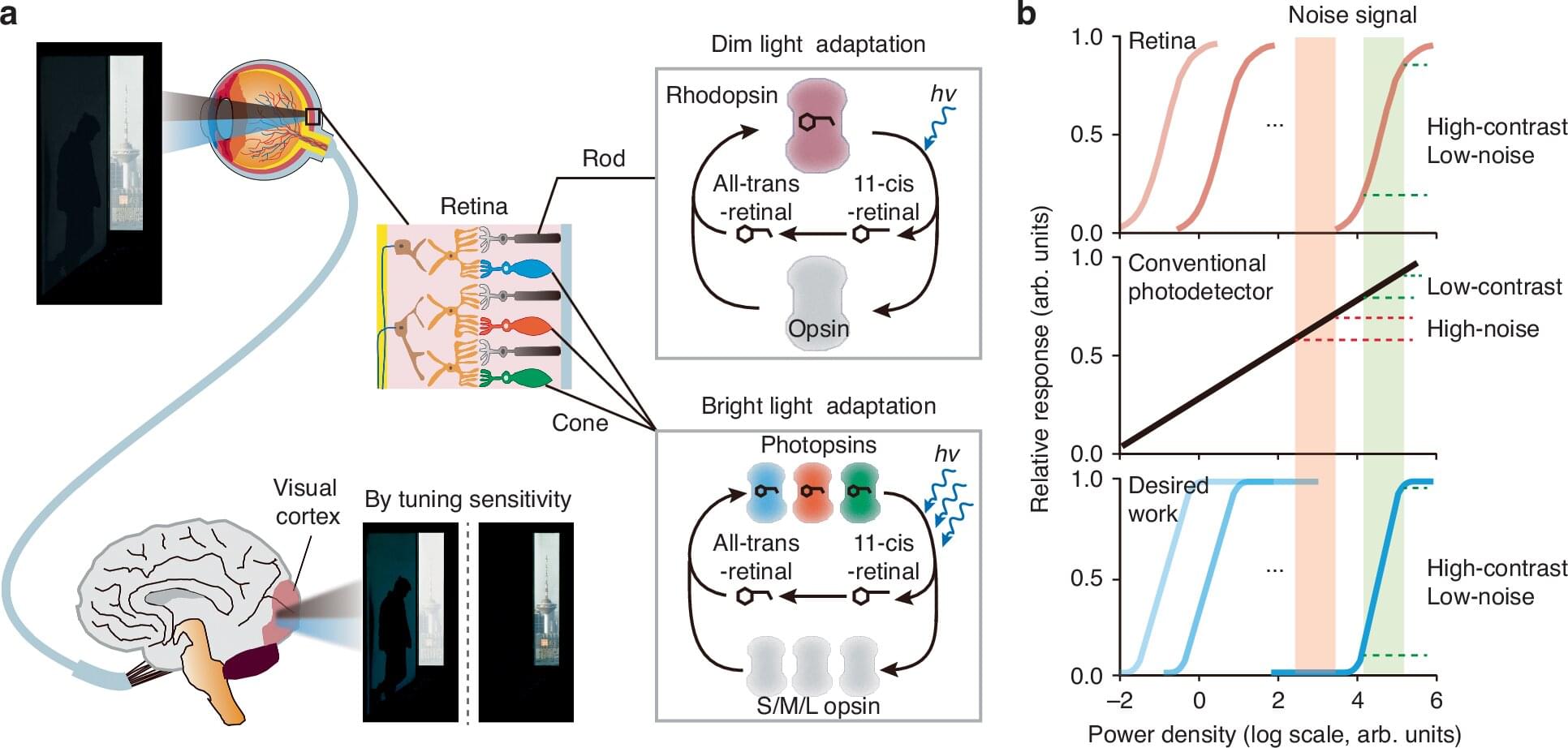

Among them is Alex Maierean (MMath ‘24), CEO of Phantom Photonics and part-time Ph.D. student at the Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC). Her startup is developing ultra-sensitive quantum sensors that can filter out background noise and detect the faintest signals, even down to a single photon—the smallest unit of light. This offers new levels of precision and stealth for industries operating in extreme environments, from the depths of the ocean to outer space.

Launched in 2023, the Velocity startup emerged from fundamental research at an IQC lab led by Dr. Thomas Jennewein, IQC affiliate and adjunct faculty in the Department of Physics and Astronomy. Today, the startup is based at Velocity where it has established a dedicated lab space to continue to develop its quantum sensor technology and build its core team.