A simple blood test picking up on biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease could help experts diagnose this condition sooner and less invasively. However, the test has not yet been brought to market.

AMD’s next-gen Sound Wave APUs teased for 2026: new Zen 6 architecture and new RDNA 5 architecture, both ready for the future of AMD Ryzen APUs.

Amid underwater mountains off the coast of Chile, scientists believe they’ve discovered 100 or so new species with the aid of a robot capable of diving more than 14,000 feet. Researchers say it demonstrates how the Chilean government’s ocean protections are bolstering biodiversity and providing a model for other countries. John Yang reports.

Notice: Transcripts are machine and human generated and lightly edited for accuracy. They may contain errors.

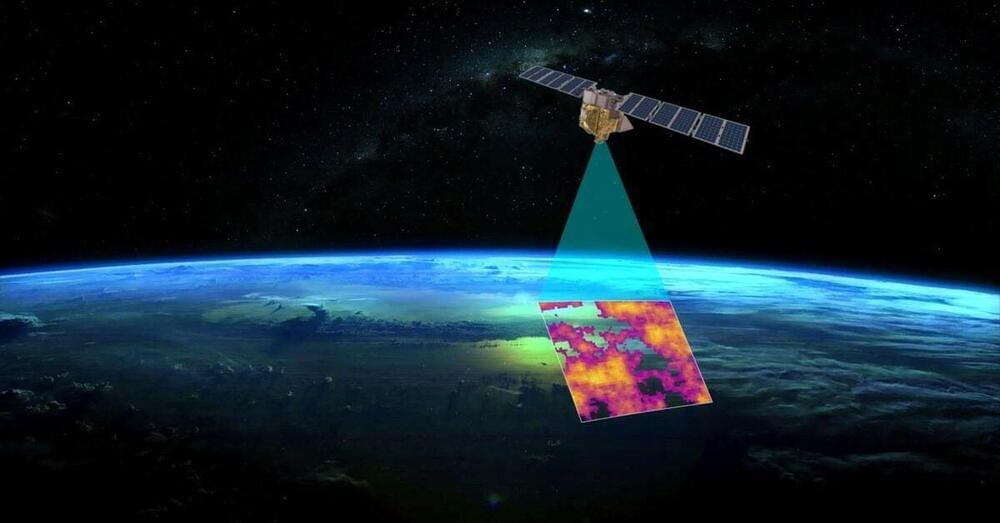

A new satellite backed by Alphabet Inc’s Google and the Environmental Defense Fund group will launch from California on Monday with a mission to pinpoint oil and gas industry methane emissions from space.

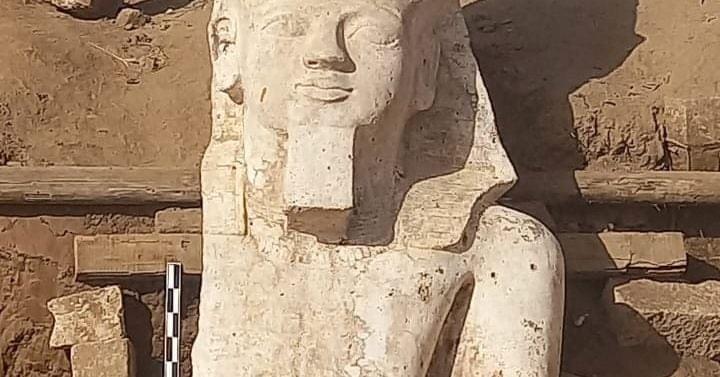

CAIRO, March 4 (Reuters) — A joint Egyptian-U.S. archaeological mission has uncovered the upper part of a huge statue of King Ramses II during excavations south of the Egyptian city of Minya, Egypt’s tourism and antiquities ministry said on Monday.

The limestone block is about 3.8 metres (12.5 feet) high and depicts a seated Ramses wearing a double crown and a headdress topped with a royal cobra, Bassem Jihad, head of the mission’s Egyptian team, said in a statement.

The upper part of the statue’s back column shows hieroglyphic writings that glorify the king, one of ancient Egypt’s most powerful pharaohs, he said.

CAPE CANAVERAL, Florida, March 3 (Reuters) — A SpaceX rocket safely lifted off from Florida on Sunday night carrying a crew of three U.S. astronauts and a Russian cosmonaut on their way to the International Space Station (ISS) to begin a six-month science mission in Earth orbit.

The two-stage Falcon 9 rocket topped with an autonomously operated Crew Dragon capsule dubbed Endeavor was launched from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral, along Florida’s Atlantic coast, at 10:53 p.m. EST (0353 GMT Monday).

A live NASA-SpaceX webcast showed the 25-story-tall rocketship ascending from the launch tower as its nine Merlin engines roared to life in billowing clouds of vapor and a reddish fireball that lit up the night sky. The rocket consumes 700,000 gallons of fuel per second during launch, according to SpaceX.

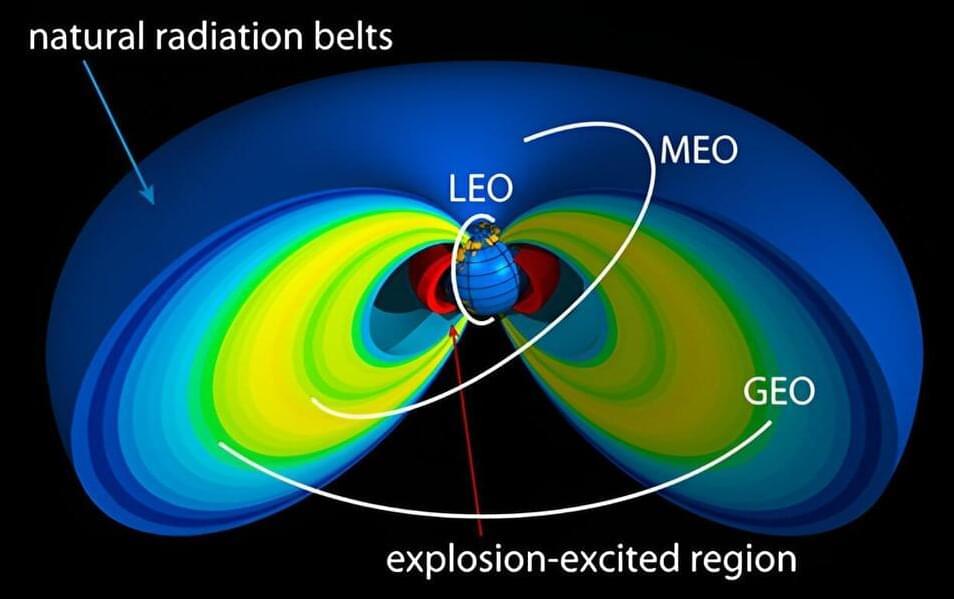

Correcting 50-year-old errors in the math used to understand how electromagnetic waves scatter electrons trapped in Earth’s magnetic fields will lead to better protection for technology in space.

“The discovery of these errors will help scientists improve their models of artificial radiation belts produced by high-altitude nuclear explosions and how an event like that would impact our space technology,” said Greg Cunningham, a space scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory. “This allows us to make better predictions of what that threat could be and the efficacy of radiation belt remediation strategies.”

Heliophysics models are important tools researchers use to understand phenomena around the Earth, such as how electrons can become trapped in the near-Earth space environment and damage electronics on space assets, or how Earth’s magnetic field shields us from both cosmic rays and particles in solar wind.

SpaceX’s next Starship to fly has passed a critical fueling test, setting the stage for a highly anticipated third launch attempt of the world’s biggest rocket.

The gleaming, stainless-steel Starship rocket and its Super Heavy booster, which together stand 400 feet tall (122 meters), were filled with more than 10 million pounds of liquid methane and liquid oxygen propellant during the recent launch dress rehearsal, which was performed at SpaceX’s Starbase facility near Boca Chica Beach in southern Texas.

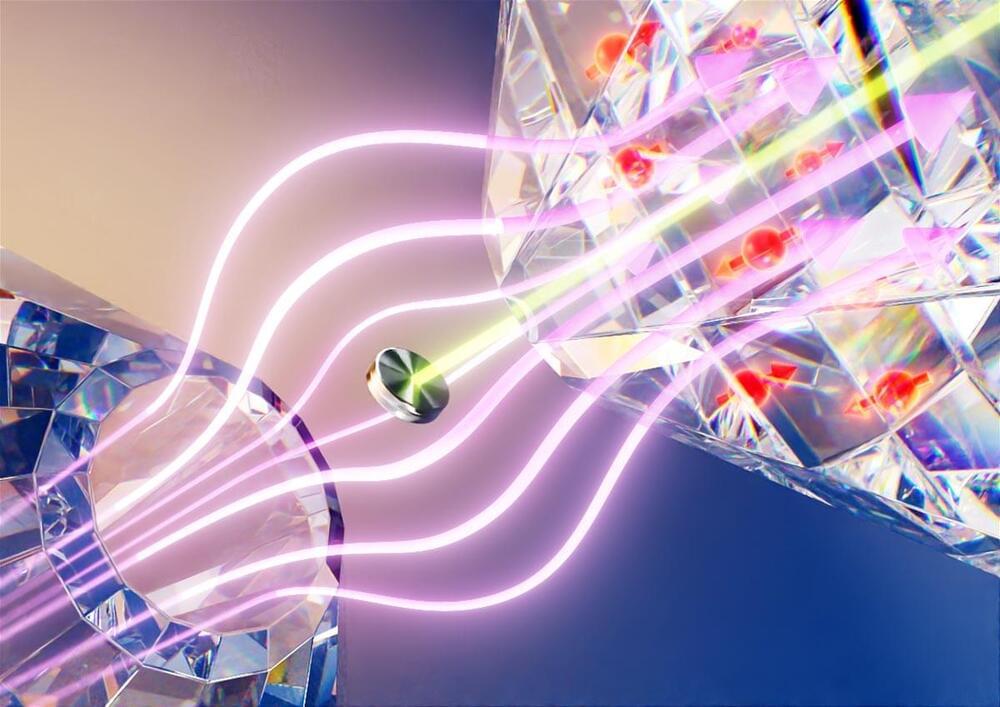

Harvard scientists have made a significant advance in high-pressure physics by creating a tool that directly images superconducting materials under extreme conditions, facilitating new discoveries in the field of superconducting hydrides.

Hydrogen (like many of us) acts weird under pressure. Theory predicts that when crushed by the weight of more than a million times our atmosphere, this light, abundant, normally gaseous element first becomes a metal, and even more strangely, a superconductor – a material that conducts electricity with no resistance.

Scientists have been eager to understand and eventually harness superconducting hydrogen-rich compounds, called hydrides, for practical applications – from levitating trains to particle detectors. But studying the behavior of these and other materials under enormous, sustained pressures is anything but practical, and accurately measuring those behaviors ranges somewhere between a nightmare and impossible.