Thousands of patients will benefit from a new cancer jab for more than a dozen types of the disease, with the NHS the first in Europe to offer the new injection. The health service is rolling out an injectable form of immunotherapy, nivolumab, which means patients can receive their fortnightly or monthly treatment in 5 […]

More Patients May Be Able To Avoid Cancer Surgery; Immunotherapy Drug Jemperli Shows Promise Across Several Different Cancer Types

Posted in biotech/medical | Leave a Comment on More Patients May Be Able To Avoid Cancer Surgery; Immunotherapy Drug Jemperli Shows Promise Across Several Different Cancer Types

Patients with certain types of early stage cancer, particularly those affecting the gastrointestinal system, may be able to avoid surgery and be successful

Light’s interference patterns may emerge from quantum particles, not waves, challenging traditional wave-particle thinking.

Imagine a world in which free-floating electric vehicles charge wirelessly as they glide down highways, laptops are hundreds of times more powerful, and clean energy flows in limitless supply.

Such a future, experts say, hinges on the development of new superconductors, or materials capable of transmitting electricity with near-perfect efficiency. The problem? All known superconductors—from pure elements like lead, tin, and aluminum to exotic compounds like niobium–titanium—must be subjected to extreme cold or pressure to function, making them impractical for widespread use. More problematic still, scientists don’t fully understand how these materials work, making it difficult to engineer better versions.

Superconductors have already made their way into MRI machines, particle accelerators, and electromagnetic levitating trains, but they are extraordinarily expensive and finicky. The real game changer, experts say, will be figuring out how to custom-design superconductors that are cheaper and more versatile.

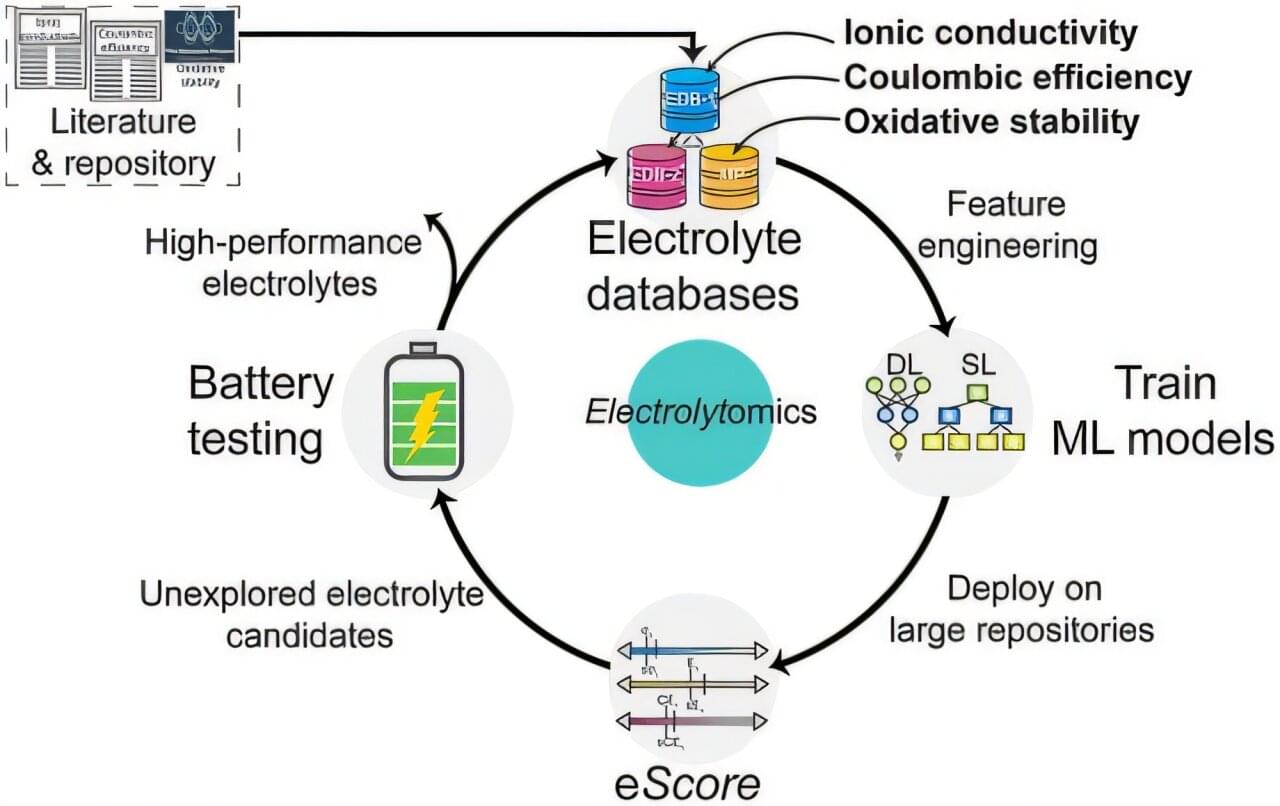

Discovering new, powerful electrolytes is one of the major bottlenecks in designing next-generation batteries for electric vehicles, phones, laptops and grid-scale energy storage.

The most stable electrolytes are not always the most conductive. The most efficient batteries are not always the most stable. And so on.

“The electrodes have to satisfy very different properties at the same time. They always conflict with each other,” said Ritesh Kumar, an Eric and Wendy Schimdt AI in Science Postdoctoral Fellow working in the Amanchukwu Lab at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME).

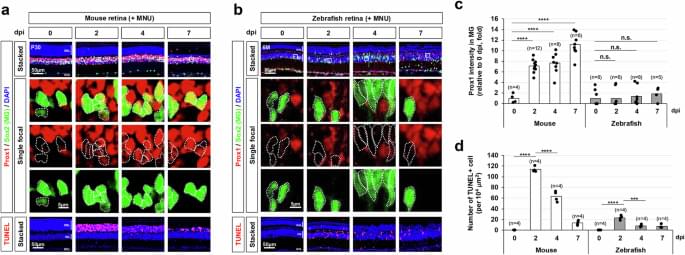

Individuals with retinal degenerative diseases struggle to restore vision due to the inability to regenerate retinal cells. Unlike cold-blooded vertebrates, mammals lack Müller glia (MG)-mediated retinal regeneration, indicating the limited regenerative capacity of mammalian MG. Here, we identify prospero-related homeobox 1 (Prox1) as a key factor restricting this process. Prox1 accumulates in MG of degenerating human and mouse retinas but not in regenerating zebrafish. In mice, Prox1 in MG originates from neighboring retinal neurons via intercellular transfer. Blocking this transfer enables MG reprogramming into retinal progenitor cells in injured mouse retinas. Moreover, adeno-associated viral delivery of an anti-Prox1 antibody, which sequesters extracellular Prox1, promotes retinal neuron regeneration and delays vision loss in a retinitis pigmentosa model. These findings establish Prox1 as a barrier to MG-mediated regeneration and highlight anti-Prox1 therapy as a promising strategy for restoring retinal regeneration in mammals.

Recovery for mammalian retinal degeneration is limited by a lack of Müller glia (MG)-mediated regeneration. Here authors show blocking Prox1 accumulation and intercellular transfer from retinal neurons enables MG reprogramming of retinal progenitor cells, promotes retinal neuron regeneration, and delays vision loss.

Abundant, low-cost, clean energy—the envisioned result if scientists and engineers can successfully produce a reliable method of generating and sustaining fusion energy—has taken one step closer to reality, as a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin, Los Alamos National Laboratory and Type One Energy Group has solved a longstanding problem in the field.

One of the big challenges holding fusion energy back has been the ability to contain high-energy particles inside fusion reactors. When high-energy alpha particles leak from a reactor, that prevents the plasma from getting hot and dense enough to sustain the fusion reaction. To prevent them from leaking, engineers design elaborate magnetic confinement systems, but there are often holes in the magnetic field, and a tremendous amount of computational time is required to predict their locations and eliminate them.

In their paper published in Physical Review Letters, the research team describes having discovered a shortcut that can help engineers design leak-proof magnetic confinement systems 10 times as fast as the gold standard method, without sacrificing accuracy. While several other big challenges remain for all magnetic fusion designs, this advance addresses the biggest challenge that’s specific to a type of fusion reactor first proposed in the 1950s, called a stellarator.

The ministry plans to support these efforts with funding from its existing robotics R&D, infrastructure, and testing budgets.